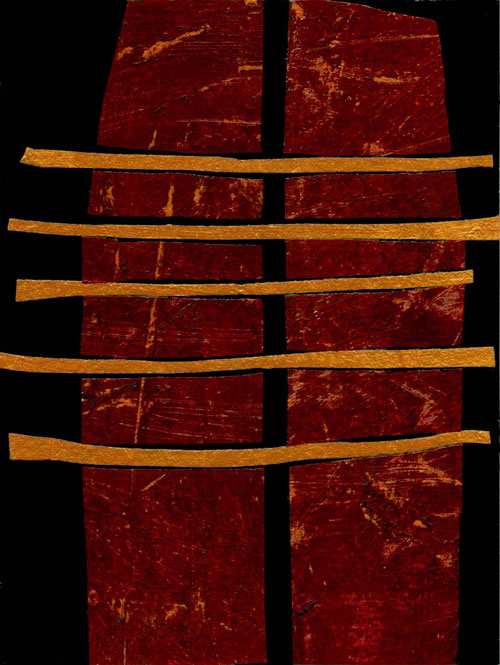

The Two Commandments © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 25/Ordinary 30/Pentecost +19: Matthew 22.34-46

Last week. Thursday. Gary and I are somewhere over the continent, making an arc toward Seattle. We are flying across the country to help with an event for the Grünewald Guild; Gary to perform, me to serve as emcee for the gala dinner and auction that will help raise funds to sustain this remarkable retreat center. This is a bonus trip, an out-of-season treat; I’ve never been to Washington State except in the summer, when I go to teach at the Guild, nor have I seen most of these folks anywhere but on the Guild’s property.

I’ve finished the collage for this post and am ambitious to think that I can write the accompanying reflection en route to Seattle. With my tray table serving as a makeshift desk, I turn to Sunday’s lection once again. Matthew gives us another encounter between Jesus and the Pharisees, with this one containing their question, “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” Quoting from the Hebrew scriptures, Jesus tells them, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments,” Jesus says, “hang all the law and the prophets.”

I pull out some notes that I had jotted down as I prepared for this trip. They are filled with impressions, questions, points of connection between the text of the scripture and the text of my life. There are scripture verses I’ve scribbled down. This passage not only drew from earlier sources but also inspired later scripture writers, so there is a web of texts that link to this one. I’ve written down Deuteronomy 6.5, from which Jesus quotes in responding to the Pharisees. It’s part of the Shema, the prayer that lies at the heart of Jewish life: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone,” the ancient prayer begins. And Leviticus 19.18: “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people,” God compels Moses to tell the people of Israel, “but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the Lord.” There is Mark 12.28-34, a parallel to Matthew’s version, which places Jesus’ questioner in a rather different light. And Luke 10.25-37, where, alone among the synoptic gospels, Jesus uses the question as an occasion to tell the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Romans 13.8-9 appears among my notes. “Owe no one anything,” Paul urges the church in Rome, “except to love one another; for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.” Galatians 5.14, in which he writes, “For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.'” And James 2.8, where the writer refers to love of one’s neighbor as the “royal law.”

Psalm 110.1 made its way into my notes. It’s the piece of poetry that Jesus quotes in the second portion of this week’s lection, where he poses his listeners a question about how David can call the Messiah “Lord,” if the Lord is his son. It seems a bit of an odd turn, a particularly circuitous question that Jesus has devised to stump his listeners. (It works, evidently. “No one was able to give him an answer,” Matthew says in concluding the passage; “nor from that day did anyone dare to ask him any more questions.”)

Looking up from my notes, I hand the gospel passage to Gary, ask him what he thinks. Does this second part of the reading offer a connection with Jesus’ words about love, or is it a distinct passage that happens to be in the same lection but requires a separate treatment? Gary ponders the passage for a bit, then suggests that each portion offers a commentary on the relationship between humans and God. The first part seems straightforward, if sometimes gut-wrenchingly difficult. In the second part, there is a deft subtlety in Jesus’ confounding question. In challenging his hearers to ponder how the Messiah can be both David’s ancestor and heir, Jesus underscores the manner in which he stands both within time and beyond it. He is Love embodied, entering into the fullness of what it means to wear flesh in this world. Yet he reminds us that Love is not bound by time, is not confined to chronology, can take us in seeming circles as we enter deeper and deeper into its mysteries.

I ponder these things, then finally I put my notes away, and my Bible, and my laptop. I am tired in body and in brain. There is time yet to try to work all the scattered notes and questions and thoughts into some sort of coherence. For now, I sit back, speeding over the darkened, unseen landscape below. Jesus’ words persist like a refrain, like a heartbeat, a steady pulse as we pass through another time zone, and another. Arcing across the country, I am traveling with someone I love, traveling toward people I love, all of whom continue to teach me about the mysteries of the simple yet achingly intricate commandment of love, this ancient law that draws us so far beyond ourselves and yet circles us deeply back within.

I close my eyes, resting before the arrival. Waiting. For now, it is enough.

How about you? What challenges and what gifts do you find in Jesus’ words in this passage? Where has love led you? Toward what—or whom—do you feel it drawing you? What sustains you along its path?

Blessings.

[To use the “Two Commandments” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

Leave a Reply