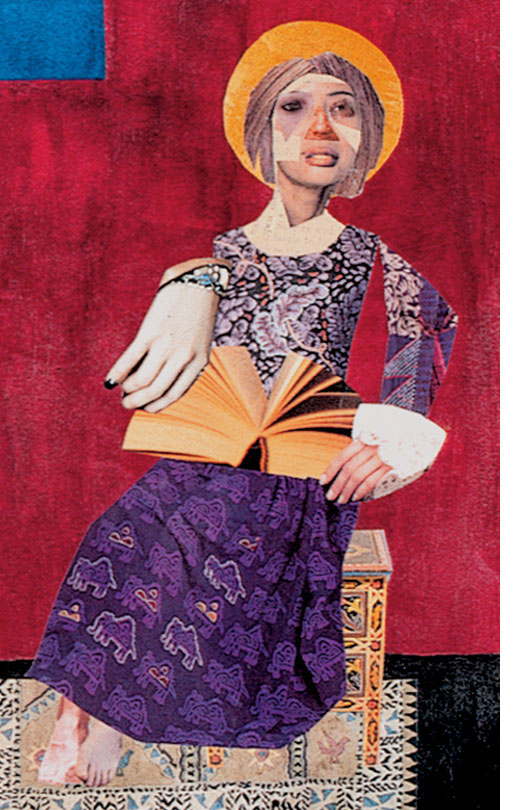

I Know Who You Are © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 4, Year B: Mark 1.21-28

There once was a time when I didn’t give much thought to what it meant to confront evil and suffering in the realm of the spiritual world. I’m mainline Protestant, after all. Spiritual warfare, as some call it, was something best left to the charismatics and others who dealt in such things.

Then I began to live and work within systems and organizations that have given me cause to think again about the notion that evil can cohere as a force, can organize and inflict itself in discrete ways. In my professional ministry and in my personal ecosystem, the years have afforded plenty of occasions to witness the ways in which chaos that exists in the spiritual world can manifest itself in the physical realm. It’s stunning, how a single individual in spiritual disarray can distribute pain and discord among an entire body of people. And the reverse: how the diffuse chaos that often lurks so easily within a system can erupt in acts of harm against particular individuals.

In this Sunday’s gospel lection, Mark tells a story that provides a vivid example of a person who has become overwhelmed by a force that is contrary to the purposes of God. In describing what harbors within the man whom Jesus encounters, Mark uses the Greek term pneumati akatharto: an unclean spirit. The uncleanness that akatharto (from the word akathartos) denotes has to do not with physical untidiness but rather with how the spirit exists in a state actively antagonistic to God, a state that the spirit has inflicted upon the man. Akathartos is the opposite of katharos (related to our word catharsis): ritually pure, clean.

Intriguing, isn’t it, that this encounter takes place in a synagogue? It underscores what I have seen time and again: that places meant for worship and seeking after God often attract the most chaotic folks. That which is opposed to God is often most drawn to those places devoted to God. Such folks are like this man who, amid the chaos, nonetheless experiences a point of vivid clarity: he—or, rather, the spirit in him—recognizes Jesus. “I know who you are,” he cries out, “the Holy One of God.”

Jesus will say, just a few verses later, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick” (Mark 2.17). It’s one thing, however, to know and seek healing for our sickness, and to minister to others who recognize their own need. More challenging to reckon with are those folks living, often without awareness, in the grip of forces opposed to God who are yet drawn toward the holy. It can take a long time before their deep, underlying hunger for God breaks through and overtakes their desire to inflict chaos in the places of sacredness.

In his healing of the man, Jesus offers a model for how we can reckon with the forces that work against God’s desire for wholeness. Jesus responds to the spirit with the calm authority that receives particular comment in this passage, both by Mark and by those who witness Jesus’ teaching and healing in the synagogue. Jesus addresses the spirit from the core of who he is. He is not exhibiting a display of magic or seeking to dazzle the crowd with a show. Rather, Jesus demonstrates his willingness to confront and call out what is contrary to God. Acting from that fiercely calm and centered place, he releases the man from the force that has tormented him.

The healthy spiritual practices of the Christian tradition give us tools to do the necessary work at the level of spirit. These practices cultivate within us the grounded, centered authority that enabled Christ to confront the unclean spirit, they help keep us clear amid chaos, and they deepen our ability to respond to the ways that disorder becomes manifest in the world. These practices, however, are not enough in themselves. As Jesus points out in the gospels, and as Paul addresses in his letters, it’s possible for us to become puffed up about our own spiritual prowess.

The desert mothers and fathers of the early church recognized this. They had a lively understanding of the ways that spiritual disorder takes form in the physical realm. They sometimes described these forms as demons, who particularly loved to hide out in the very practices that these desert folk sometimes became proud of—extreme fasting, prayer, and the like. This story comes from the desert tradition:

[Amma Theodora] also said that neither asceticism, nor vigils nor any kind of suffering are able to save, only true humility can do that. There was an anchorite who was able to banish the demons; and he asked them, ‘What makes you go away? Is it fasting? ’ They replied, ‘We do not eat or drink.’ ‘Is it vigils? ’ They replied, ‘We do not sleep. ’ ‘Is it separation from the world? ’ ‘We live in the deserts.” ‘What power sends you away then?” They said, ‘Nothing can overcome us, but only humility.’ ‘Do you see how humility is victorious over the demons?’

In my own spiritual practice, I have taken to opening my day by offering the prayer known as St. Patrick’s Breastplate, also called Deer’s Cry (for its association with the legend that St. Patrick prayed it when he and his companions were in peril, and the prayer caused them to take on the appearance of deer and thereby elude their attackers). Though the prayer originated sometime after St. Patrick, it is an old, old prayer of encompassing—what the Celtic folk call a lorica—that in a poetic and profound way calls upon God to protect us from the forces that seek to work against God. I’m particularly fond of the version that Malachi McCormick offers in his book Deer’s Cry. Published by his small press, The Stone Street Press, Deer’s Cry offers Malachi’s translation of the prayer (alongside the Old Irish version), handwritten with his charming calligraphy. I gradually committed the prayer to memory some time ago. I pray it not as some kind of magic charm but rather as a reminder that I go into my day, and into the world, in the encompassing of God, who bids me rely completely on the power of God rather than on my own devices. It’s a prayer that, honestly prayed, cultivates humility, an awareness of how we are entirely dependent upon God. It’s this humility that in turn fosters the type of calm, centered authority by which Jesus acted in confronting the unclean spirit.

This gospel story reminds us not to give more power to the presence of evil than is warranted; obsessing over chaos can breed it. Rather, the story challenges us to confront evil where we find it. The demons—by whatever form or name we know the presence of disorder—fight hardest when we, like Jesus, look them in the face. But this is what depletes evil of its power. It cannot bear being named, challenged, called out.

Where do you personally witness the forces that work against God? What do you think about those forces, and how do you reckon with them? How do you seek God’s protection against them? Are there ways you feel called to confront the presence of chaos? What practices help keep you centered in, and reliant upon, the power of God?

May you go with the encompassing of Christ, who does not abandon us to chaos but instead accompanies in every realm. Blessings.

[Amma Theodora story from The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward, SLG.]

[To use the “I Know Who You Are” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]