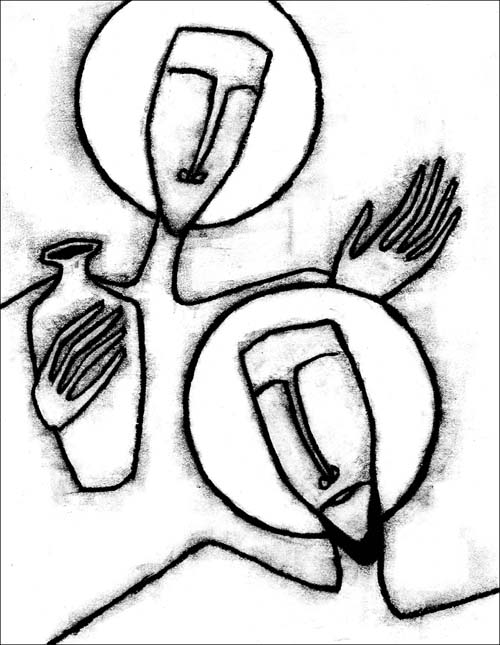

Image: Into the Wound © Jan Richardson

Image: Into the Wound © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Easter 2: John 20.19-31

“Have you believed because you have seen me?” Jesus asks Thomas as he, at Jesus’ invitation, reaches his hand into the wounds of the risen Christ. “Blessed are those,” Jesus goes on to say, “who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”

While Jesus accords special honor to those whose faith does not depend on sight, surely he does not mean that the gift of blessing is reserved solely for those who can make the leap of imagination toward belief. Christian history would indeed come to label Thomas with the moniker—something of an epithet—of “Doubting Thomas,” (though elsewhere, in John 11, Thomas displays remarkable courage and devotion to Jesus) and cast a suspicious and sometimes deadly eye on doubt. At the same time, through much of its history the Christian tradition has offered tools and gifts specifically designed to foster sight and thereby deepen belief.

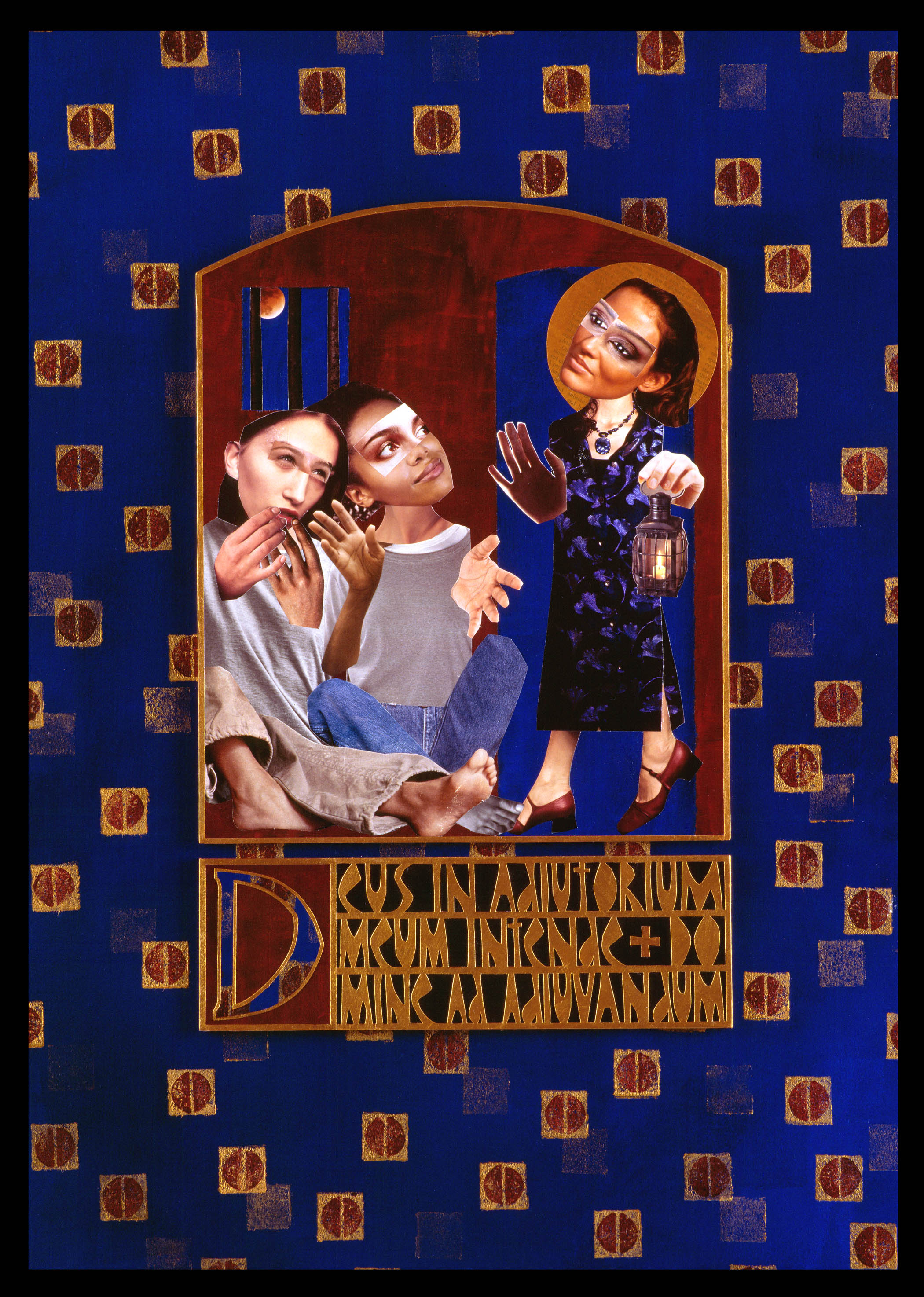

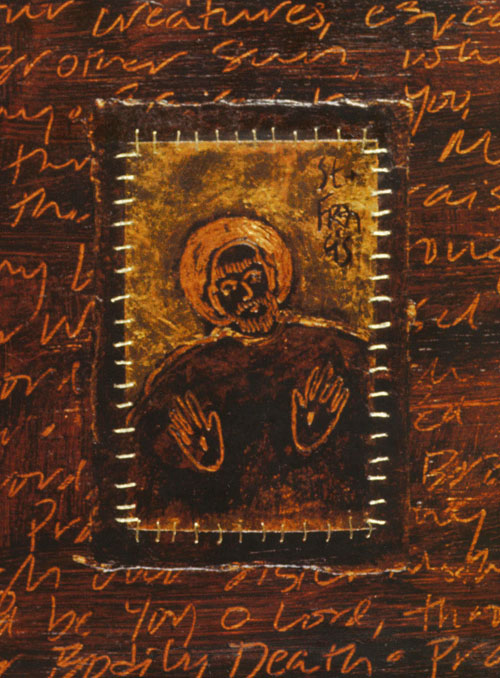

Thomas would have found good company amongst many Christians in the Middle Ages, when there arose a form of devotion that gave particular attention to the wounds of Christ as an entry into prayer and contemplation. The writings of medieval mystics both helped give rise to this form of devotion as well as to articulate it. With an approach to both flesh and spirit that can be challenging for us to comprehend in our day, these mystics saw in Christ’s wounds, particularly the wound in his side, an array of meanings. In their prayerful imagining, Christ’s wound became, among other things, an opening through which he offers his life-giving sustenance as a mother shares her milk with her child; a womb-space that offers the possibility of rebirth; and a place of union between lover and beloved.

These ideas about Christ’s wounds made their way into images that medieval artists created for the purpose of devotion. We see this, for instance, in paintings that depict the wounded Christ and his mother. As Christ offers his wound to the viewer, Mary offers her breast with a nearly mirrored gesture that suggests the similarity of the sustenance they give. We see signs of this devotion also in a number of illuminated manuscripts that include life-sized renderings of Jesus’ side wound. Divorced from his body, the wound itself becomes an object of contemplation, making an intriguing portal into the page and doorway into prayer.

This kind of depiction of Jesus’ wound sometimes appears in illuminated prayer scrolls that were used by women in childbirth. The women placed the prayer scrolls around themselves as birth girdles, with the depiction of Christ’s wound serving not only as an object of contemplation but of hoped-for protection as well. One can imagine the laboring women saw this wound-symbol as a confirmation that Jesus, who knew what it meant to suffer in bringing new life, offered sustenance to them as they did so. More than one writer has remarked on the striking similarity that the depiction of Jesus’ wound bears to female genitalia (noting also the similarity between vulva and vulnus, wound), prompting one to wonder if those who clung to Christ’s wounds in prayer noted the similarity of these portals by which new life enters. (But, as another writer has noted, how could they have missed noticing it?)

While such a vivid approach to the wounds of Christ may strike our 21st-century sensibilities as odd or gruesome, this form of contemplation was not seen as an end in itself. In the myriad ways that mystics and artists reflected on Christ’s body, it seems clear that they understood the flesh of Christ as a threshold: that his wounds were an entryway, a portal into God. As Sarah Beckwith describes it, the wounded body of Christ offered a rite of passage that held the possibility not only of a deeper relationship with him but also a redefinition of oneself.

Contemplating the wounds of Christ could also prompt medieval Christians to touch the wounds of the world. In his book on traditional religion in 15th- and 16th-century England, Eamon Duffy notes that “the wounds of Christ are the sufferings of the poor, the outcast, and the unfortunate.” He goes on to write that devotion to the wounds of Christ often translated into acts of charity. Such acts became a tending of the living, wounded, corporate body of Christ.

These imaginative approaches to Christ’s wounds, and the access they offered to medieval folk who sought intimate acquaintance with him, do not dismiss or justify the violence of the crucifixion story. Encountering these visual images, however, has challenged me to wonder what sort of doorway they offer to me, and to us, in these days that, as they ever have been, are so profoundly marked by violence.

I have come to see more clearly the ways that being in the world and loving one another—even from our most intact, integrated places, much less our less-intact ones—exposes us to wounding, to the giving and receiving of pain. Christ’s wounds exemplify this. They underscore the depth of his willingness to enter into our loving in all its hurt and hope and capacity for going horribly wrong. In wearing his wounds—even in his resurrection—he confronts us with our own and calls us to move through them into new life.

Christ beckons us not to seek out our wounding, because that will come readily enough in living humanly in the world, but rather to allow our wounds to draw us together for healing within and beyond the body of Christ, and for an end to the daily crucifixions that happen through all forms of violence. The crucified Christ challenges us to discern how our wounds will serve as doorways that lead us through our own pain and into a deeper relationship with the wounded world and with the Christ who is about the business of resurrection, for whom the wounds did not have the final word.

As Thomas reaches toward Christ, as he places his hand within the wound that Christ still bears, he is not merely grasping for concrete proof of the resurrection. He is entering into the very mystery of Christ, crossing into a new world that even now he can hardly see yet dares to move toward with the courage he has previously displayed.

As we move into this Easter season, how do we see the wounds of Christ in the wounds of the world? How might we be called to reach into those wounds—not to wallow in them, not to become overwhelmed by them, but to touch them and minister to them and help to turn them into doorways that draw us deeper into Christ?

In this season of resurrection, may you see the risen Christ all around you. May you be blessed in your seeing, and lean yourself into the new world that he offers to you.

P.S. For previous reflections on this passage, see Easter 2: Into the Wound and Easter 2: The Secret Room.

[To use the image “Into the Wound,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

Beckwith and Duffy references:

Sarah Beckwith, Christ’s Body: Identity, Culture, and Society in Late Medieval Writing (New York: Routledge, 1993), 60.

Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c. 1400-c. 1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 248.

A portion of this reflection has been adapted from Garden of Hollows: Entering the Mysteries of Lent & Easter © Jan L. Richardson.