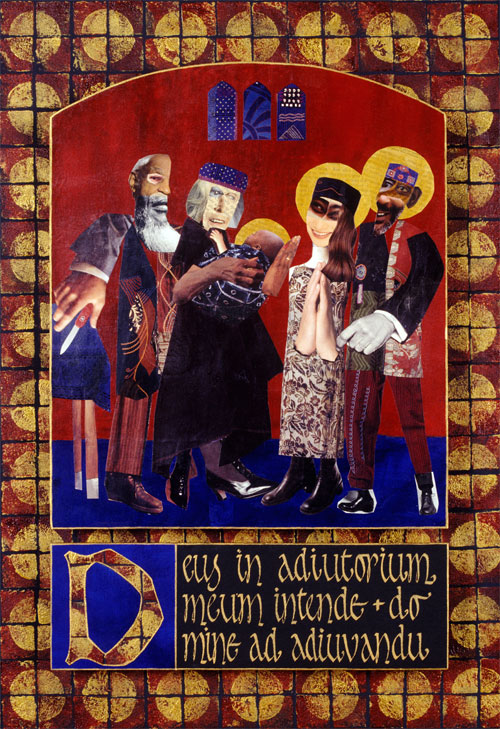

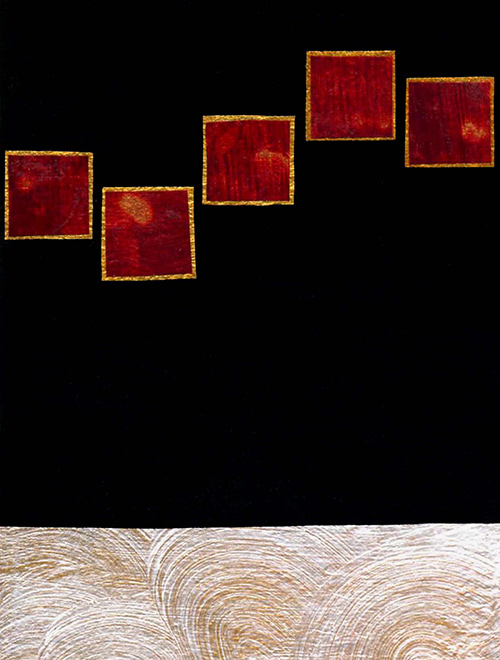

Baptism of the Beloved © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 1/Baptism of the Lord: Mark 1.4-11

Here’s how I imagined my time between Christmas and Epiphany: lots of quiet, a good dose of solitude, room to breathe during the lovely pause between the Almost End of the Holidays and the (in my calendar, at least) Actual End of the Holidays. I envisioned an expansive space of respite in which to gather the energies I had spent since before Advent and to do some internal preparation for the year to come. I imagined walks, and naps, and copious amounts of reading.

I have indeed had some splendid time away from work in the past two weeks (to the extent that a writer/artist/minister can ever lay her work aside). It’s included great visits with family and with distant friends passing through town, and a few but not enough walks, and some but not enough reading, and lovely time with my sweetheart Gary, who saw rather less of me during Advent than usual.

I have found myself, however, having a hard time resisting the urge to fling myself into the projects, old and new, awaiting me at this turning of the year. I love my work (most days), I am eager to pick up existing projects and get started on new ones, and more and more I feel the press of time. As a result, I haven’t been entirely successful in resisting the pull of those projects during these post-Christmas days. I’m aware that I never really put them down in the first place.

So here on the day after Epiphany, I’m pondering what I need in order to enter the new year feeling refreshed instead of frenzied. I’m realizing that being eager to dive back into the projects is not the same thing as being ready—really ready, internally ready, soulfully ready—to take up the work that lies ahead.

And here comes Jesus in this week’s gospel reading, heading for the Jordan, presenting himself to John the baptizer, submitting himself to the sacramental waters. Jesus, who has been who knows where for something like three decades, discerning and preparing. He is ready to fling himself into the work awaiting him. And yet not ready. He needs something. A river. A ritual. A recognition. You are my Son, the Beloved, he hears as he comes up from the waters, drenched with the Jordan; with you I am well pleased.

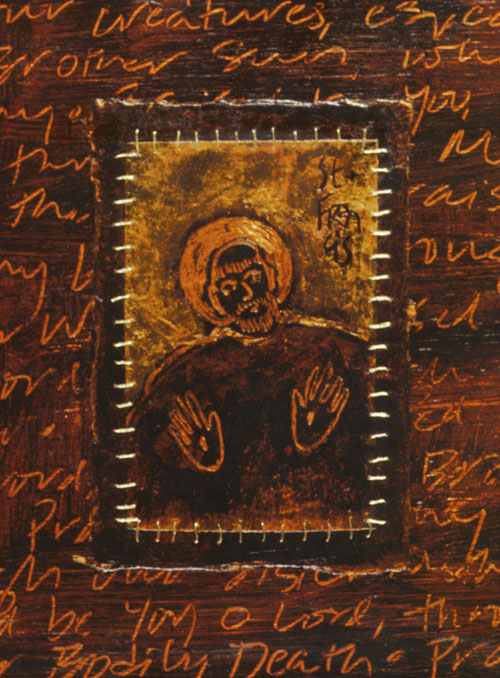

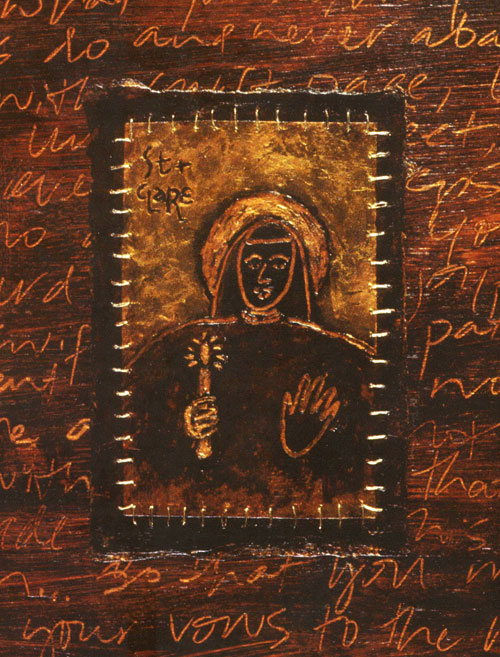

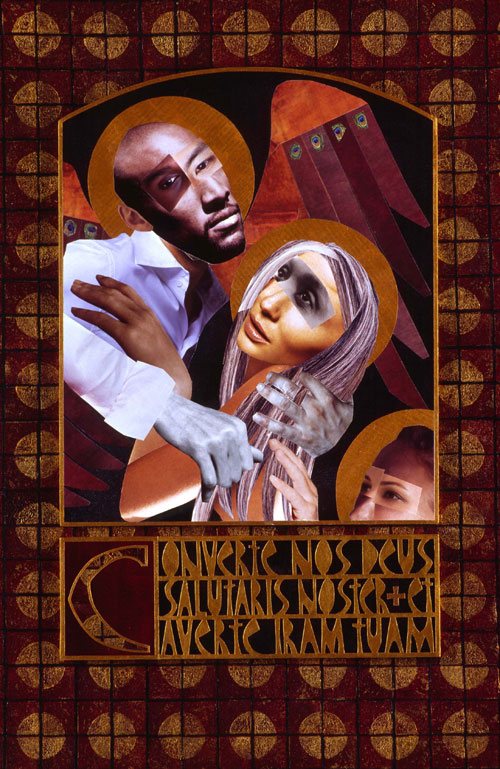

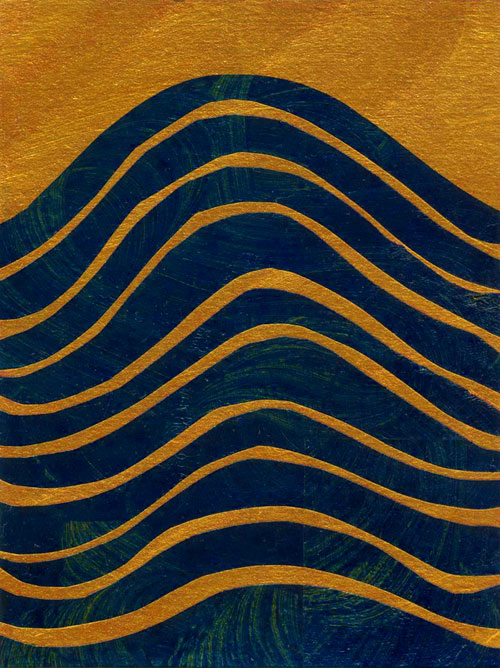

In their depictions of the baptism of Jesus, medieval artists often painted the river rising to meet the naked Messiah, surging up to enfold him, arcing around his waist. Often this appears to be for modesty’s sake, though the usual transparency of the river doesn’t entirely accomplish that aim. At times, however, the rising of the river seems to be for nothing but pure joy: the creation reaching out to meet and enfold Christ, the God who has become intimately, incarnately intertwined with the world. In some depictions, such as this one in a medieval Psalter, even the fish rise with the waters, leaping as if in recognition of the one who has waded into their midst. Leaping like John the Baptist did when he and Jesus met for the first time, as Luke tells it, in the waters of their mothers’ wombs.

There are times when our lives rise up to claim us, occasions when that which we were born to be leaps up to envelope us. Something calls our name. Reminds us we are blessed and beloved. Baptizes us. Sends us forth.

When we are graced (and challenged) with moments when the work ahead of us is clear, when we know what it is we are to do, sometimes there is preparation still to be done. Jesus knew this, knew he needed the ritual that John had to offer, knew he needed that baptism and blessing. And so, standing on the hinge of this year, seeing with some measure of clarity the work that lies ahead, the work that I was created to do, I’m giving some thought to what kind of blessing I need to seek so that I can dive into that work already drenched. What ritual, what respite, what river do I need to take myself to?

How about you? What do you need as you launch into this new year? Are you ready enough, or is there yet some preparation, some blessing you need in order to bring your whole self to what lies ahead? How might you seek this? Who can help?

In the days to come, may God drench you, bless you, call your name.

Beloved.

[To use this image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. For all my artwork for the Baptism of the Lord, please see this page. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]