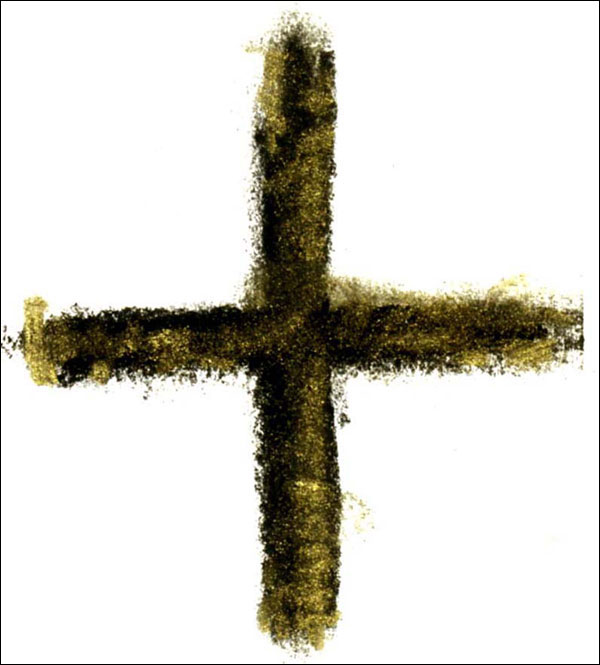

Mud In Your Eye © Jan L. Richardson

One evening during my senior year of college, I had dinner with a couple of friends I hadn’t seen since high school. As we caught up over our meal, I shared that I was preparing to go to seminary to become a minister. Upon hearing this, one of my friends immediately launched a series of questions. What did I think of homosexuality? Fornication? The inerrancy of the Bible? It was clear that my friend, who (I had quickly learned) thought the idea of women in ordained ministry was both unscriptural and immoral, wasn’t really interested in a conversation. He was administering these questions not as a way of learning how I was sensing God’s call in my life but rather as a litmus test to see just how far I had strayed from God’s will for me as a woman.

There are questions, like those from my high school friend, that seek to keep us in our place, and there are questions that help us find the place where we belong. Our Gospel lection this week, John 9.1-41, invites us to hear both kinds of questions and to notice the vast difference between them.

John draws us into the story of a man, blind from birth, who has an encounter with Jesus that results in his being able to see. For those who had known the man as a blind beggar, the change in his condition is deeply unsettling. They begin to ask questions, first of one another, then of the man. They take him to the Pharisees, who ask questions of their own. Then they bring in the man’s parents and ask questions of them; they, in turn, direct the questioning back to the man. Lifted from their context, here are the questions they pose:

Is this not the man who used to sit and beg?

Then how were your eyes opened?

Where is he [Jesus]?

How can a man who is a sinner perform such signs?

What do you say about him?

Is this your son, who you say was born blind? How then does he now see?

What did he do to you? How did he open your eyes?

There is a sense of mounting tension in John’s story, a steady escalation of frustration and fury on the part of the questioners each time the man responds. He is telling them nothing they want to hear, nothing that fits into the beliefs and experiences that they carry. The newly-sighted man possesses a remarkable sense of calm, answering in the only way he knows how: from his own experience. “One thing I do know,” he says, “that though I was blind, now I see.”

When the man’s inquisitors press further, he finally asks a question of his own. “I have told you already, and you would not listen. Why do you want to hear it again? Do you also want to become his disciples?” His questions are too much for the questioners. John tells us that they begin to revile the man, finally sending him away with an abrupt, rhetorical question: “You were born entirely in sins, and are you trying to teach us?”

Their questions induce a sense of claustrophobia in me. These questions are not doorways into conversation. These questions are fences, these questions are walls. They are designed to reinforce the boundaries of what these people already know, and to keep their landscape of belief, experience, and knowledge safely contained.

These questioners are arrogant. They are aggravating. It would, therefore, be easy to dismiss them as the bad guys in this story. Reading this text in the context of lectio divina, however, urges me to consider where I find those maddening questioners inside myself. And I feel a measure of compassion for them, because I know the times when, faced with something beyond my own experience, I have scrambled for an illusion of security. I know the times, at least some of them, when I have retrenched the boundaries of my beliefs, when I have been overly defensive of what I think I know, when I have asked a question—of someone else or of myself—that built a wall rather than opening a door.

One of the best practices we can engage in, during Lent or any season, is to ask the questions, of others and ourselves, that expand our vision rather than confining it. Good questions carry something of a ritual within them, a sense of the sacramental: they do for us what the act of washing in the pool of Siloam did for the muddy-eyed man. Good questions rinse our eyes. They help us practice seeing. They widen and deepen our vision. They clarify our perception of what is present in our lives and of what is possible. They remind us, as a friend recently reminded me, that we may not always get answers, but asking a good question makes way for a response.

John wants to make sure that we know that Siloam, the name of the pool in which the man washed his eyes, means Sent. Here I have to make the theological observation: Is this cool or what? We are all being sent. Sometimes we are sent beyond the boundaries of what others find acceptable or comfortable or convenient. Sometimes we are sent beyond the limits of our own vision. Whether or not we know where we are going—and sometimes especially when we think we know where God means for us to go—we are ever needful of learning how to see. Like Jesus with the blind man, God calls us to participate in claiming the vision that God gives us, so that, as Jesus says, God’s works might be revealed in us. In order to know where and how and by whom we are being sent, we need to keep visiting Siloam to do the washing that will keep our eyes clear.

John closes this story with questions that are good eye-clearing questions. Jesus, John tells us, finds the seeing man and asks him, “Do you believe in the Son of Man?” He answers Jesus’ question with a question: “And who is he, sir? Tell me, so that I may believe in him.” His question leads, not to a wall, or to a law, but to worship.

It’s the Pharisees who offer the final line in the long litany of questions that this story contains. Overhearing the exchange between the sighted man and Jesus, they ask, “Surely we are not blind, are we?”

Are we?

How well is your spirit seeing these days? What questions are coming your way in this season? What questions are you offering? Are they doorways or walls? How do they take you deeper into the mystery of Christ? Are there deeper questions beneath your questions? What questions will help keep your eyes clear so that you can see, and be sent?

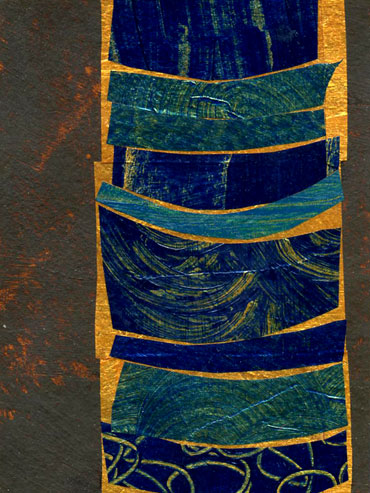

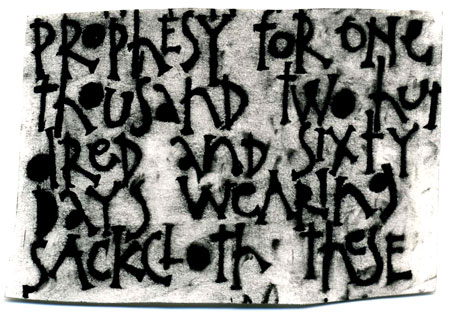

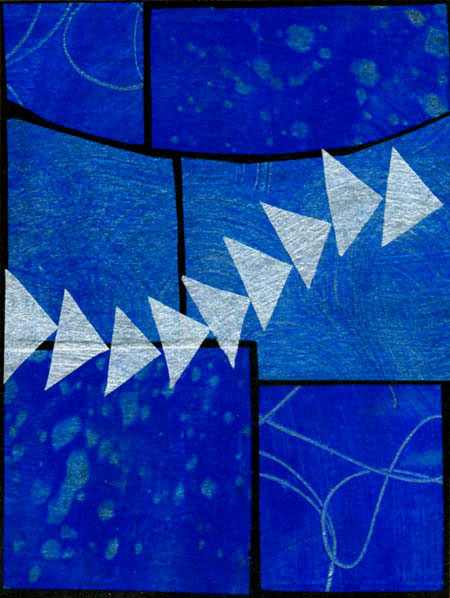

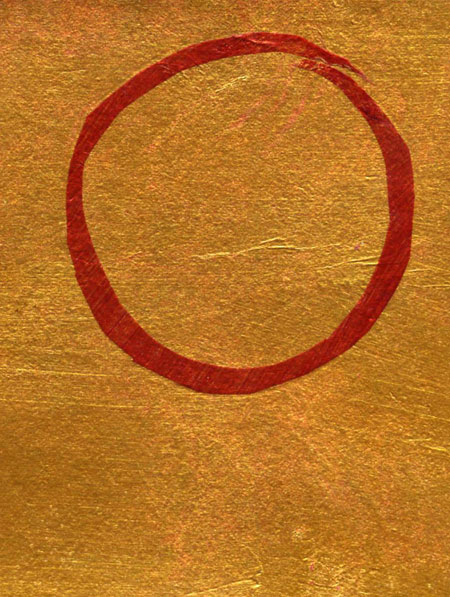

[To use the “Mud In Your Eye” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]