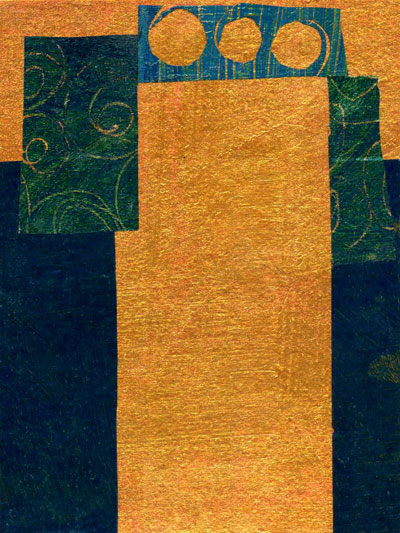

The Sheepgate © Jan L. Richardson

This week’s gospel lection, John 10.1-10, introduces a paired set of images that Jesus plays with in intriguing ways: the shepherd and the gate.

I have to admit that of all the ways of describing Jesus, the image of him as a shepherd is one I’ve never particularly gravitated toward. I suspect this owes to a combination of factors: I live in a culture that is far removed from the agrarian setting in which Jesus employed this image, and I grew up around cows, so am not very knowledgeable in the ways of sheepdom. I suspect, however, that the real reason that I struggle with shepherd imagery is this: I am resistant to being herded. I am also all too aware of how badly things can go wrong when we are overly willing to let ourselves be led. (“Lambs to the slaughter” comes too easily to mind.)

The thing about living with the lectionary is that it confronts us with texts and images that may not sit easy with us, so John’s passage has been a good challenge for me this week. In letting the text work on me, I’ve come to appreciate how Jesus offers several points that provide crucial clarity about the sheep-and-shepherd thing.

First, Jesus does not call us to follow him in a mindless fashion. Part of my trouble with ovine imagery is that I’ve heard plenty of times that sheep are stupid, and so what does this metaphor say about us? It was illuminating to attend a workshop last year with Roberta Bondi, who was one of my professors at Candler School of Theology. In the course of the workshop, during which Roberta spun wool as she talked, she challenged this pervasive notion about sheepish intelligence. It’s not that they’re stupid, she told us; they are prey animals, not predators, and so their instincts strike us as counterintuitive or just plain dumb, because they don’t think as we do. Gail Ramshaw, in her wondrous lectionary resource Treasures Old and New, adds another layer of insight, observing that “At the most ancient level of biblical storytelling, sheep are highly respected, for without their life, communal survival would not be possible. Contemporary interpretation of the Bible’s sheep stories,” she goes on to write, “needs to balance its characteristic talk about how stupid sheep are with the economic reality that sheep were the primary life source for the people, God’s gift of sustenance for the people.” Christ likens us to sheep not because he expects us to be vapid, but because he counts us as valued.

Second, Jesus calls us to follow him in the context of relationship. He wants us to know him. “He [the shepherd] calls his own sheep by name and leads them out,” Jesus says in this passage; “…the sheep follow him because they know his voice.” Jesus’ call is grounded in his desire for a relationship with us, to know us and to be known by us. He expects us to engage in discernment, to ask questions, to be wise in the ways that we follow him. It’s important to note that this passage follows on the heels of his healing of the blind man in John 9, which we visited on Lent 4; this week’s gospel lection is a continuation of Jesus’ teaching about how he desires us to see.

A third point of clarity that Jesus offers in this passage is that we are not to follow him just because he says so, or because hellfire and damnation await us if we don’t. The presence of the shepherd is never threatening; rather, it is precisely the opposite. The shepherd is the one who extends radical hospitality to the sheep; he protects them against whatever would threaten them, even, as Jesus states repeatedly later in this chapter, laying down his own life for them. Ramshaw points out that “herders in that part of the world lay their own bodies down for a night’s rest in the gap of the fence, the body of the shepherd thus serving as the gate.” Indeed, Jesus describes himself in this passage not only as the gatekeeper of the sheepfold but as the gate itself.

Jesus’ image of himself as a gate underscores the fact that his way is one of hospitality, not of threat. The gate—the one that Christ opens to us, the one that Christ himself is—does not open by way of force. Rather, this entry becomes compelling because of the one who offers it, who opens it to us as a way of blessing. “I came that they may have life,” Jesus proclaims in the final verse of this text, “and have it abundantly.”

Jesus means for us to have this abundant life not solely in some future world but also in this present world. He intends, too, for us to have this life together. Christ calls us to fields where following him means tending to one another—to our sheepmates. In the midst of my resistance to being herded, I have to take care not to forget that there are good reasons to travel in flocks. Ramshaw offers a good reminder here—and if I keep turning to her this week, it’s partly because I’ve just recently found her treasure of a book, but mostly because she’s been particularly helpful to me in thinking sheepishly; she writes, “Shepherding stresses the communal nature of the sheep. Our singular noun flock is one made of many. The church proclaims the good news that I am not alone. We are the flock, and we share a common life.”

As you navigate this shared life, what, or who, is determining the direction of your path these days? Which has more influence over the shape of your path—your reactions, or your intentions? How are you experiencing the hospitality of Christ? How might he be challenging you to know and hear him in this season? What gate might he be beckoning you toward?

[To use the “Sheepgate” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

April 11, 2008 at 11:29 PM |

I’ve always bought into the sheep=stupid line of thought. How refreshing to learn that they were so respected and valued – as are we….thank you!

April 12, 2008 at 11:20 PM |

It’s nice to read this a week after enjoying the retreat you led at Wisdom House.

You refer to the “hospitality of Christ,” and I think of my own understanding of the good shepherd as a kind and protecting friend. I think shepherding is tough work–it requires some insight. To be cared for with understanding is to be deeply loved by a good friend. So the image works for this vegetarian!