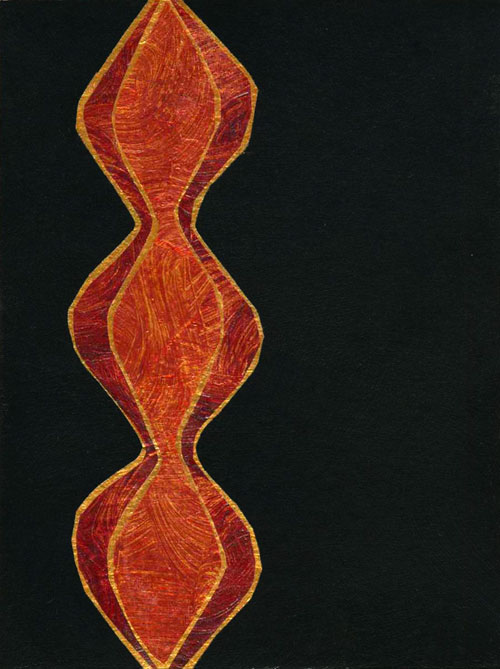

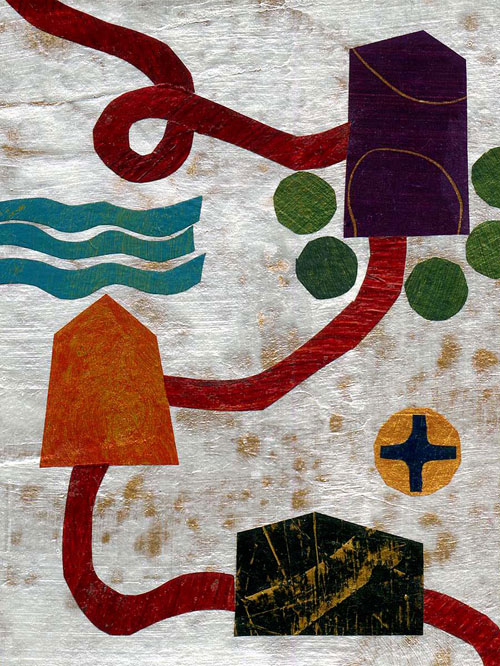

A Place for the Prophet © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 8/Ordinary 13/Pentecost +2: Matthew 10.40-42

In her book Dakota: A Spiritual Geography, Kathleen Norris tells a story that’s said to come from a Russian Orthodox monastery. A seasoned monk, long accustomed to welcoming all guests as Christ, says to a young monk, “I have finally learned to accept people as they are. Whatever they are in the world, a prostitute, a prime minister, it is all the same to me. But sometimes,” the monk continues, “I see a stranger coming up the road and I say, “Oh, Jesus Christ, is it you again?”

Hospitality is on Jesus Christ’s mind in this week’s Gospel lection, Matthew 10.40-42. In this passage we find Jesus continuing his instructions to the disciples as he prepares to send them into the towns to “heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse lepers, and cast out demons” (Matthew 10.8). He tells them, “Whoever welcomes you welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me. Whoever welcomes a prophet in the name of a prophet will receive a prophet’s reward….”

I find myself thinking that it’s one thing to welcome a prostitute or a prime minister, as the longtime monk had learned to do. But a prophet?

As guests go, prophets are not the easiest folks to have around. In their role as the mouthpiece of God, they tend to come out with things that can make a host uncomfortable. The Hebrew prophets, after all, weren’t so much foretellers as forth-tellers: they perceived the present injustice among their people with uncommon clarity, and they addressed it with uncommon candor. “Thou art the man,” Nathan says to David (2 Samuel 12.7). “The dogs shall eat Jezebel within the bounds of Jezreel,” Elijah says of Ahab’s wife (1 Kings 21.23). “Do not pray for the welfare of this people,” God says to Jeremiah. “Although they fast, I do not hear their cry, and although they offer burnt-offering and grain-offering, I do not accept them; but by the sword, by famine, and by pestilence I consume them” (Jeremiah 14.11, 12). Famine and destruction, devastation and woe: the prophets were pretty intense fellows. Even in their hopeful moments, which produced some of the most amazing and sustaining poetry of the Bible, they still confront their hearers with words that make it hard to relax around them.

It’s not always easy to welcome those who remind us what it is we’re supposed to be in this world, who call us to live as the people God created us to be, who ask so much of us. It can sometimes be a tiresome, “Jesus Christ, is it you again?” kind of prospect.

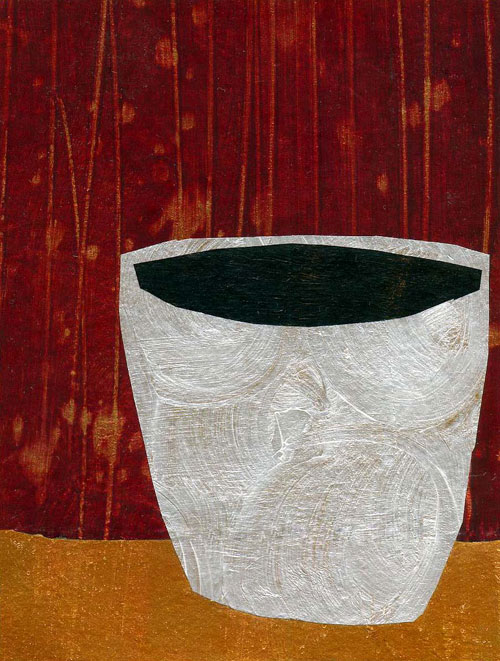

But I think of a woman who extended this kind of hospitality to a traveling prophet. Her name, like that of so many women, went unrecorded; history recalls her simply as the Shunammite woman. Having befriended the prophet Elisha and recognizing him as a holy man, she convinces her husband that they should provide a space for him. I love the homely, hospitable details that the story in 2 Kings 4.8-37 provides. “Let us make a small roof chamber with walls,” says the woman of Shunem, “and put there for him a bed, a table, a chair, and a lamp, so that whenever he comes to us, he can go in there” (2 Kings 4.10).

Elisha recognizes the gift, and after a time, he wants to know how he can repay the woman for her hospitality. “What is to be done for you?” the prophet asks. And thus begins a tale of birth, and death, and the raising of the dead, a story that echoes in Jesus’ sending of the disciples to do the same kind of work.

I think of the Shunammite woman as I ponder Jesus’ words about how those who welcome a prophet in the name of a prophet will receive a prophet’s reward. Which at first doesn’t hold a lot of appeal, given the usual “rewards” bestowed upon prophets. For their efforts, they are dangerously prone to imprisonment. Beheading. Crucifixion. Slaughter by various methods. But in the land of Shunem, a woman welcomed a prophet with a room, a bed, a table, a chair, a lamp. Looking for no reward, the woman provided a sacred space for a holy man. And within the space of her own self, an unexpected child began to grow.

It’s a strange economy, this kind of hospitality. We can’t know what we will set in motion when we offer some space to the ones whom Jesus tells us to welcome. We offer a cup of cold water, or a place to rest, or an extra room, or a corner of our heart; we cede some precious territory to one who comes with a word from God; we open ourselves to remembering who it is God put us here to be, and all of a sudden, we’re carrying something we never expected to carry. Maybe it’s not a literal child, as it was for the Shunammite woman. But this kind of hospitality always makes room for new life to take root in us and to come through us in ways that we can’t predict. That’s part of the strange economy, the curious ecosystem of hospitality: open a space to the holy stranger, and God creates a sacred space within our own selves. An extra room in our own souls. A place for God to grow.

What’s hospitality like for you these days? How do you make room for those who challenge you to remember who God created you to be? What kind of holy space might God be wanting to create in your life? In you?

Blessings to you as you discern where to extend a welcome, and where to receive one.

[To use the “A Place for the Prophet” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]