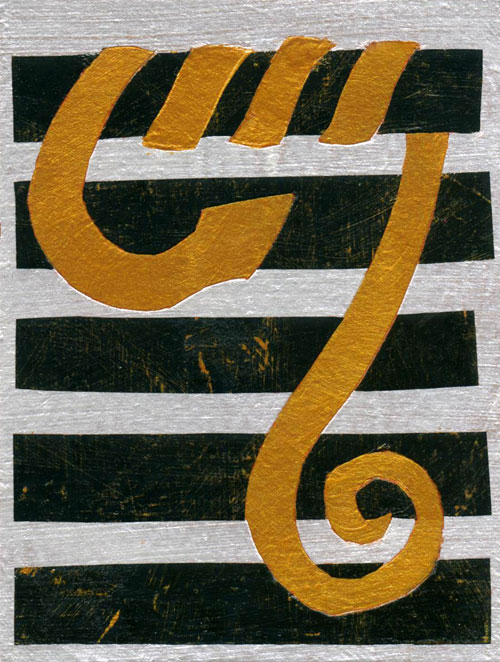

Image: The Temple by Night © Jan Richardson

Image: The Temple by Night © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Palm Sunday: Mark 11.1-11

After sending for the colt.

After the procession.

After the palms.

After the cloak-strewn road.

After the hosannas.

After blessed is he who comes

in the name of the Lord.

After all this, Mark—alone of all the gospels—tells us that Jesus goes into the temple and looks around at everything.

He does not teach. He does not preach. He does not heal. He does not confront or challenge. He does not even speak; neither does he cross the path of anyone who requires his attention. Mark conveys the impression that here, in this sacred space that lies at the heart of his people, Jesus is quite alone, and that it is night.

Jesus simply looks around. What is it that he sees in the temple by night?

The gospels vary in their account of Jesus’ relationship with the temple, and how much time he has spent there. Taking together their accounts, we know Mary and Joseph took him there as an infant for the rituals that occurred forty days after a birth. He made the journey to the temple every year with his family for Passover, most memorably at the age of twelve, when his parents, missing him on the way home, went back and discovered him in conversation with the teachers. Matthew tells us that the devil took Jesus to the pinnacle of the temple, urging him to jump, that angels would catch him. John in particular emphasizes Jesus’ presence at the temple earlier in his ministry, where the temple features in such stories as Jesus’ encounter with a woman caught in adultery. It is at the temple, according to John, that Jesus proclaims himself as the river of life and as the light of the world, beginning to take into his own self, as Richard Hays has pointed out, the purpose of the temple as the focal point of the liturgy and life of the people of Israel.

This is the place that holds the memories of Jesus and the collective memory of his people. And it is to this place that Jesus returns, after the palms, after the procession, after the shouts of proclamation have vanished into the air. He will come back tomorrow, Mark tells us, and he will turn over the tables and drive out the buyers and sellers and castigate the people for turning this house of prayer into a robbers’ den. He will return yet again over the next few days to teach, to provoke, to watch a widow drop two precious coins into the offering box. And soon he will die.

But for now, for tonight, in this holy place at the heart of his people, Jesus merely looks. He peers into this sacred space that is inhabited and haunted by his own story. And perhaps it is this story he sees again this night. Perhaps he sees Mary and Joseph coming out of the shadows, carrying their infant son. Perhaps he sees Simeon gathering his young self into his arms, singing about salvation and a light for revelation, joined by the old prophet Anna, who raises her voice in praise. Perhaps Jesus sees again the twelve-year-old who conversed with the temple teachers, and the tempter who tried to lure him to fling himself from the pinnacle of this place. Perhaps a woman, once trapped and terrified, stands before him again, this time with the light of forgiveness and healing shining through her eyes.

And perhaps in this place, where Jesus is alone-but-not-alone, they gather about him, reminding him why he has come, calling him to remember, offering their blessing for the days ahead. Perhaps in this space, after the palms and before the passion, Jesus is able simply to rest. To remember. To breathe. To be between.

And you? What are you between? Where is the space that invites you to be alone but not alone, to allow the memories to gather and bless you, to offer strength for the days ahead? What is the place that beckons you to breathe, to rest, to look? What is it that you see in that space? What stirs in the shadows?

Blessings to you in the spaces between.

Resources for the Season: Looking toward Lent

[To use the image “The Temple by Night,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]