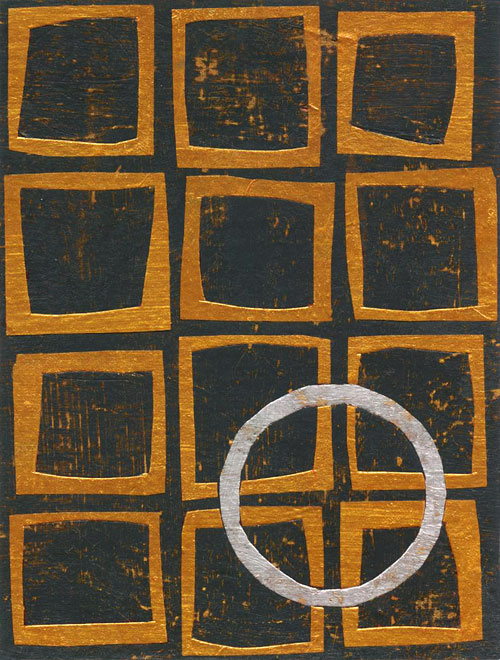

The Shape He Makes © Jan Richardson

The Shape He Makes © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Proper 18/Ordinary 23/Pentecost +15, Year C (September 5): Luke 14.25-33

And so we come to one of the most wrenching and challenging passages that Jesus will ever utter. It’s as if he’s been saving up hard things to say, and now, with what Luke describes as “large crowds” traveling with him, Jesus takes this opportunity to lay these hard things on the masses. He speaks of what is necessary to lay aside in order to follow him: he tells of hating one’s closest family members, of hating life itself, of carrying the cross, of giving up all our possessions.

One might well think he’s looking to thin out those crowds that are following him.

It’s tempting to want to tone Jesus down here, to ratchet him back a bit, or to try to explain away the harshness of his words. But the Greek word that’s translated as “hate” really does mean hate. Miseo is the Greek root; it can also be translated as to pursue with hatred or detest. It’s the same word that Jesus used earlier in Luke, when he said, “Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man” (Lk. 6.22).

In commentaries on this passage, the word hyperbole comes up; Jesus is being excessive, the commentators say, in order to make his point. It’s true that it does help to read this passage alongside its parallel in Matthew 10.34-39, a passage that is no less difficult—it’s the one where Jesus talks about bringing not peace but a sword and about setting family members against one another—but Matthew does frame Jesus’ words a bit differently than does Luke. In the Matthew parallel, Jesus speaks not of loving him instead of loving our family members but rather of not loving him less than we love them.

I don’t find myself particularly interested in trying to explain Jesus away, disturbing and wrenching though his words about family and cross and possessions may be. But I can tell you a few of the things that I found myself thinking about during the many hours that I sat at my drafting table this week, pushing pieces of painted papers around while I—a woman deeply entwined with family and other treasures of this life—struggled with this passage.

I thought of how Jesus involved himself with such intentionality in the lives of those around him: how he knew real human friendship—think of the siblings Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, for instance, whose hospitality and companionship he enjoyed. I thought of how, in his agony on the cross, one of his last actions was to give his mother and the beloved disciple into one another’s care: “Woman,” he says to the one who bore him and raised him and who, as Simeon had promised so long ago, now felt the full force of a sword piercing her heart, “here is your son.” And to the beloved disciple standing beside her, Jesus says, “Here is your mother.”

Sitting at the drafting table, working with the pieces, I thought of the stunning pages from the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels, those remarkable books created in the early centuries of Christianity in the British Isles. In particular I thought of the carpet pages, where all manner of creatures and symbols interlace and intertwine and entangle themselves with one another in configurations from which it would be impossible to extricate them. Always, the cross lies at the heart of these intricate pages: the entwining and entanglement serve to reveal the cross in both its simplicity and its complexity.

I can tell you that I thought of one of the books I’m reading right now, Strangers to the City, a reflection on the Rule of Saint Benedict by the splendid Michael Casey, a Cistercian monk who writes with such engagement about what he calls the “creative monotony” of the monastic life. Small wonder, perhaps, that I should be reading his chapter titled “Dispossession” while wrestling with Jesus’ words about attachments. Casey writes about how the poverty to which Christ calls us is rooted in poverty of spirit, and that this is intimately linked with humility—that lesson that Jesus had for us in last week’s gospel lection. Casey writes of how, without this humility in which we acknowledge our absolute dependence upon God, our practices of dispossession—of giving away what hinders us from God—can become a source of pride, which becomes its own obstacle to seeking God.

I thought of my friend Dee Dee Risher, who wrote an article years ago in the lovely, much-missed magazine The Other Side, about her journey to do what Jesus speaks of in this passage: to give away what clutters her path to God. In the article, titled “A Spirituality of Contentment,” Dee Dee told of occasions when she felt self-righteous for her chosen self-deprivations, realizing later that the smugness she felt in simplifying her life masked a deeper discontent. She began to recognize, as she puts it, that “my external changes had far outpaced my internal transformation.” And she began to give prayerful thought to the deeper practices that God was inviting her toward—practices that included honoring her home as a place of hospitality for her own soul, and for God as well.

As the collage finally began to take shape, I thought of what I have allowed to enter my life: the people, the places, the possessions. I thought of all that I am entangled with, the intertwinings and interlacings that mark my life. I am unwilling to hate the people I hold precious; I am reluctant to let go completely of the loveliness that God offers to us in the tangible things of this world. I think of the furniture my grandfather made for me by hand, the painting my friend Phyllis gave Gary and me for our wedding, the books that feed my soul and mind, the soft bed I share with my beloved. Yet I take Jesus’ words to heart, his fierce call to follow him and love him with a whole and undivided heart. And so I carry some questions with me. These entanglements that twist through my life with a complexity that sometimes rivals a page from one of those luminous Gospel-books: like one of those books, do they reveal the shape of a cross imprinted upon my life? All that I let enter, all that I choose, all that I allow to pierce me: does it create a pattern of life that takes on the same configuration as the Christ who gave himself with such abandon to those whom he loved?

The cruciform life—a life that seeks to follow the Christ whose path intersected so completely with our own—is not one that can be imposed upon us. It is a mystery that we can enter into only by choice, and that we must navigate with a spirit of discernment. Carrying the cross is not about casting about for a heavy burden to pick up; neither does it require us to seek out situations of pain and danger that will cause damage to the person God calls us to be. It’s about seeking the pattern of life that will open us the most fully to the God who created us in our particularity. The shape the cross takes for me—artist, writer, minister, wife, and in all my other particularities and peculiarities—will be different than it takes for you. The things I need to let go of, to choose against, to turn away from in order to make a space for Christ at the center of my life may well be different than what you need to let go of. And what I need to allow in, to reshape me, to pierce me—as Mary chose, as Jesus himself chose—will be particular to my own life as well. I think again of the carpet pages in those ancient Celtic Gospel-books, how they are remarkable in their differences, each one revealing the cross in the stunning distinctiveness and intricacy of its particular pattern.

The Gospel lection this week doesn’t leave me with a lot of coherence; what I have are these questions, these pieces that showed up at the drafting table. How do these pieces of the gospel lection sit with you this week? What are you allowing into your life right now? The people and possessions and habits that twine through your days: What shape do they make of your life? Amid the complexities of your living, what configuration will make space for Christ to be the center, the source that creates something whole from the pieces? Are there pieces you need to release, to turn away from? Are there pieces you need to invite in?

May Christ bless your path—and be your path—in the days to come.

[To use the image “The Shape He Makes,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

Related artwork: Finding the Focus.

Related artwork: Finding the Focus.