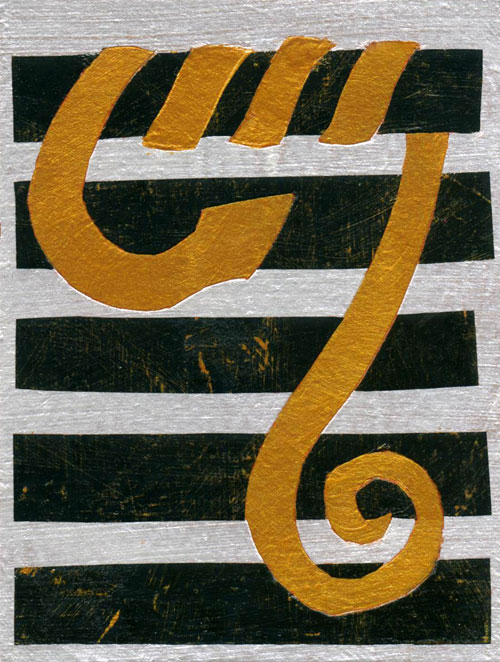

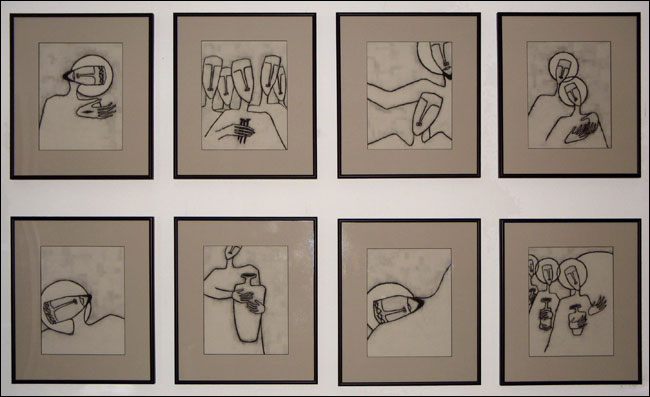

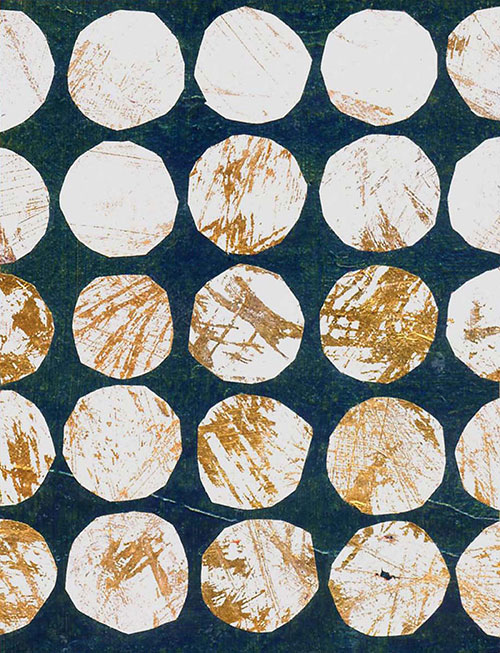

Image: Into the Seed © Jan Richardson

Image: Into the Seed © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Lent 5, Year B: John 12.20-33

So do you remember that kerfuffle back in the 90s when Mattel brought out a new Barbie doll called Teen Speak Barbie? The Barbies were programmed to say what the company considered typical adolescent girl phrases. Some of the dolls were heard to utter, “Math class is tough!” A protest ensued, and Mattel excised that phrase. The story still circulates, with the troublesome phrase often (mis)quoted as “Math is hard!”

At this point in the Lenten journey, I find myself getting in touch with my Inner Barbie. Call her Ecclesiastical Barbie, perhaps, or Exegetical Barbie. (Ooooh, can’t you see her now, complete with the Barbie Dream Church and Deacon Ken?) These days, when someone pulls the string on my Inner Barbie, she’s likely to say, “Lent is tough!” or “These lections are hard!”

The scripture passages that this season presents to us are intense, dense, and complex. They are laden with metaphor and meaning, swirl with constellations of symbols and images, and shimmer with vivid emotion and crucial teaching. These texts challenge us to look with honesty at our lives, they confront us with our attachments, and—in a phrase I recently encountered—they urge us to sit with our own mirrors.

Lent is not for sissies.

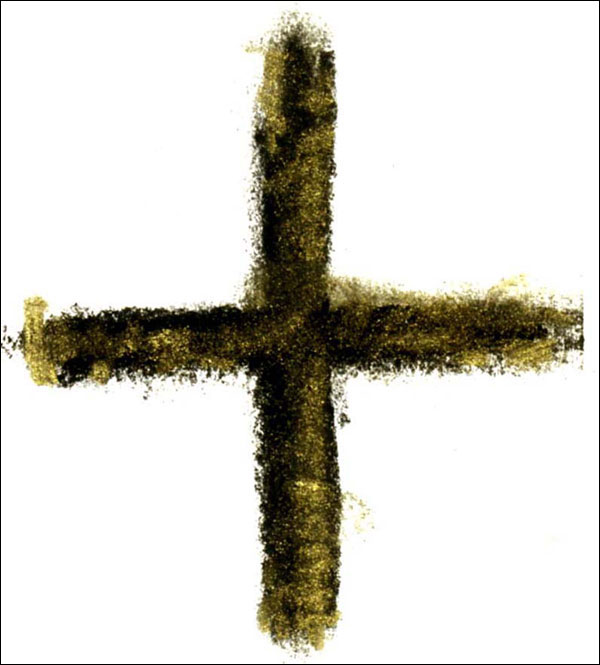

In these past few weeks, we have traveled with Jesus into the wilderness, listened to his challenge to discern between the things of heaven and the things of earth, witnessed his outraged and outrageous cleansing of the temple, and overheard him liken himself to the serpent that Moses raised in the wilderness. Now he comes along, in this week’s gospel reading, speaking of grain and dying, losing one’s life and keeping it, hating and loving. We hear a thundering voice from heaven speaking of glory, and Jesus talking of being raised up from the earth.

The import of these Lenten texts is all the more intense for the surety of Jesus’ violent death that looms ahead. As we walk with Jesus through these weeks, we know what we are walking toward. And so his words carry extra weight, and we bend closer to capture them, as we do with someone we know is not long for this world—but who is already beginning to see things we cannot see, and speaking a language we do not yet understand.

Unlike others loosing the tethers that have held them to this life, however, Jesus retains a passionate interest in this world. Despite any impression he may give to the contrary (“those who hate their life in this world will keep it,” he says this week), Jesus does not perceive this world, this life, merely as a prelude to heaven or as a stockyard for weeding out the blessed from the damned. He seeks, rather, to train our eyes to perceive the kingdom of heaven tucked into the midst of this very world.

Teaching us to see the kingdom requires symbol, myth, metaphor, story. It requires the visual poetry that Jesus repeatedly uses as he turns to the things of earth to describe the things of heaven: yeast, seeds, dirt, water, fish, lilies of the field, birds of the air. Again and again he employs the ephemeral as he seeks to explain what is eternal. His doing so both comforts and unsettles; taking what is familiar to us, he turns it on its head, and us as well. How will we ever come to understand such a language?

We may feel daunted at this point in the season. I do. So suffused with meaning and messages, not to mention impending murder, these passages can overwhelm with their density and intensity and with their challenge to us to hold their paradoxes and untangle their meanings. Their lines somehow intertwine with the stuff of my days, drawing me deeper into the questions they pose about what my life is really about. There is so much to discern, to sort through, to sift.

In the midst of feeling daunted, I find myself thinking of the mystic poet who asked, “What is the cure for love? More love.” The formula holds true elsewhere. The cure for mystery? More mystery. The cure for paradox? More paradox. Last week’s readings from Numbers and the gospel of John reminded us that the cure for snakebite lay in looking upon a serpent. And in such a way this season beckons us to consider that we find our cure not by shrinking from what besets and befuddles and daunts us but by looking deeper into those very places, and finding the treasure that God has placed within them.

Go into the things you shrink from, Jesus tells his hearers—and us—in this passage. Go into the questions, the mysteries, the paradoxes, the seeming contradictions. Go into the Lenten dying that is not dying after all. We work so very hard at letting go, sometimes, trying to train ourselves to release our grip on all that is not God. But what if it is not about giving up but giving in? Falling into dirt, as Jesus says here. Going where grain is supposed to go. Following the spiral within the seed that takes us deeper into the dark but also—finally, fruitfully—out of it.

The lectionary interrupts this passage before its end; Jesus’ conversation with the crowd actually extends to verse 36. After Jesus finishes his discourse, here’s what John tells us Jesus did: he hid from them. And perhaps that’s what Jesus means for us to do at this point on the Lenten path: to hide. To not be set on figuring everything out but rather to let at least some part of ourselves, for some space of time, withdraw. To cease from wrestling with the questions and mysteries and simply rest with them and give in to them. To secret our souls like a seed in the earth. To see what grows.

How is it with your soul at this point on the Lenten path? As you work with these texts, how are these texts working on you? What questions have they stirred for you in these days? How do you respond to the mysteries and paradoxes they hold? Can you rest with those questions and mysteries? What do you need?

May you fall into, rest into, a place that will tend and nourish you in these days. Blessings.

Resources for the Season: Looking toward Lent

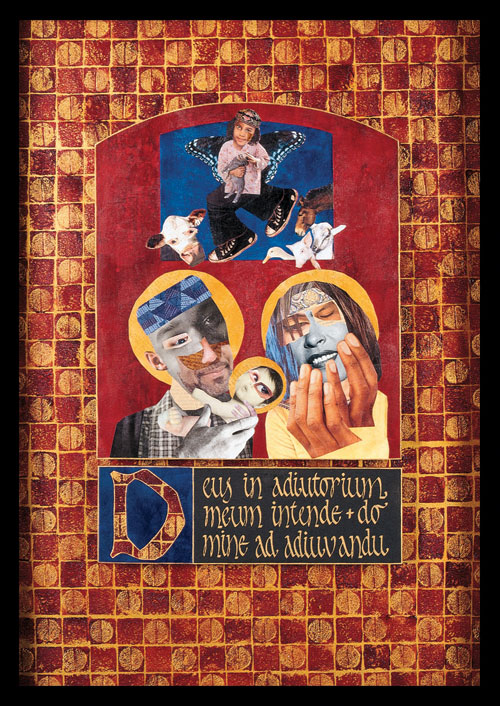

P.S. Happy Eve of the Feast of the Annunciation! Falling on March 25, this feast celebrates the radical yes that Mary said to Gabriel when the angel beckoned her to become the mother of Christ. For some of my artwork and reflections on the Annunciation, visit Getting the Message and The Hour of Matins: Annunciation.

[To use the image “Into the Seed,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]