Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 6, Year B: Mark 1.40-45

One of the aspects that most engages me about the new book I’m working on (a book of prayer and reflection that draws on the lives of women from the Judeo-Christian tradition) is getting to meet the women who show up along the way. Drawing as I do from several thousand years of history, I encounter these women primarily in fragments they have left behind. Stories, scriptural references, letters, prayers, poetry, visionary literature, journals, biographies, artwork, and more: the sacred texts of these women’s lives take a multitude of forms. Often working amid forces that sought to constrain and circumscribe them, women continually stun me with the persistence and creativity by which they embodied and passed down the Word from generation to generation.

In doing some research recently, I met a woman whose work is stoking my imagination. Born in the southern United States in 1837, Harriet Powers grew up in slavery and spent much of her life near Athens, Georgia. We know a scant handful of facts about her life. She had children, she was emancipated, she and her husband purchased a farm, she worked as a seamstress. We know about her primarily because of two of her stitched creations that survived: a pair of quilts.

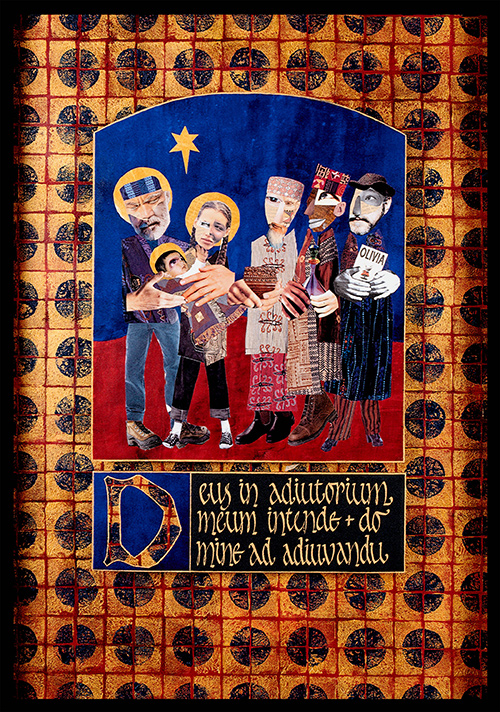

Known as Bible quilts, Powers’s creations captivate with their style and with the stories they tell. Most often using the technique of appliqué, and perhaps drawing on the long tradition of appliqué that came from Benin (once known as Dahomey) in West Africa, Powers stitched her quilts with bold, colorful figures of humans, animals, and celestial bodies: sun, moon, stars. Frame by frame, her quilts tell stories that Powers absorbed, pondered, and reconstructed in an intensely personal and artful fashion. Not only did she include biblical stories such as Adam and Eve, Jonah and the Really Big Fish, the crucifixion of Jesus, and John’s vision of the angels with their trumpets and vials; Powers also stitched in local legends and references to astronomical and climatological events that she had heard of or experienced. Her stitched stories included “The independent hog that ran 500 miles from GA to VA,” “the falling of the stars on November 13, 1833,” and “a man frozen at his jug of liquor” on Cold Thursday in 1895. (See the quilts, and a photograph of Harriet Powers, in a brief bio here.)

We know some of Powers’s thoughts about her work through several people who recorded her reflections. Describing her first Bible quilt, now in the Smithsonian Institution (her second quilt resides in the collection of The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston), Powers said it was “a Sermon in Patchwork,” and that she desired to “preach the gospel in patchwork, to show my Lord my humility…”

As experts have pointed out, Powers’s quilts are not the size of typical bed covers; they are significantly wider than they are long. When one takes that together with Powers’s own words about her work, it becomes tantalizing to consider the possibility that she created them primarily as a form of proclamation. With the vibrant vocabulary she had at hand, she bore testimony to the Word who had taken flesh in her own life.

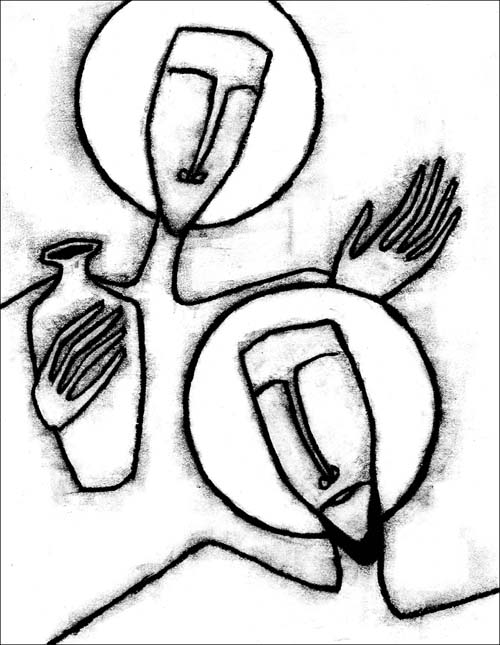

We saw this impulse toward vernacular proclamation in Peter’s mother-in-law last week, who responded and testified to Jesus’ gift in the only way she knew how: the vocabulary of a meal. This week we see the impulse toward testimony in the form of a man who finds healing in the presence and in the touch of Jesus. In this Sunday’s gospel reading, Mark tells us of a man whom Jesus releases from leprosy. Jesus attempts to confine the man’s response. “See that you say nothing to anyone,” he tells the one whom he has healed; “but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded, as a testimony [Greek marturion, which also means witness] to them.” The man, however, cannot contain himself. His testimony spills over the boundaries that Jesus has set. Mark tells us that the man “went out and began to proclaim [Gk. kerusso, also translated as to make known, to preach] it freely, and to spread the word, so that Jesus could no longer go into a town openly, but stayed out in the country; and people came to him from every quarter.”

Like Harriet Powers, like Peter’s mother-in-law, this healed man offers his testimony with the only vocabulary he has: in this case, his own body, his own flesh, healed and made whole. In this man, the medium is the message. His body proclaims everything he knows about Jesus. Voice lifted up, arms flung wide, he is an open book, a gospel: the good news is embedded in his body, a living testament to the incarnate God who tangles Godself up in the business of our bodies.

Freed from the bondage of slavery, Harriet Powers offered her testimony stitch by artful stitch. Released from the imprisonment of illness, Peter’s mother-in-law gave her testimony through ministering to Jesus and his companions at the table. Set loose from the captivity of leprosy, the healed man proclaimed his testimony with every fiber of his flesh. Each with their own medium, they did what lay in their power to do.

How about us? How do we offer our testimony about the one who has freed us? What medium do we have at hand to proclaim the news of how Christ has worked, and works still, to release all people from every form of captivity and bondage? What is the unique vocabulary that God has given to you to articulate how God takes shape in your life? How willing are you to use that vocabulary in ways that only you can express?

In every word, with every gesture, by every art, through every means, may we be a living gospel, for the life of the world. Blessings.

[Harriet Powers’s “Sermon in Patchwork” quotation is from Harriet Powers’s Bible Quilts by Regenia A. Perry. See also Stitching Stars: The Story Quilts of Harriet Powers by Mary E. Lyons.]

[To use the “Testimony” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]