If the Yoke Fits © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 9/Ordinary 14/Pentecost +3: Matthew 11.16-19, 25-30

In the church that my sweetheart Gary attends, there is a young man who has a syndrome that affects his cognitive abilities. Among the challenges this poses, both for him and those around him, is that he doesn’t always make good choices for himself, and this has sometimes made his road pretty rough. At a recent worship service, in which we celebrated the ordination of one of the church’s pastors, this young man was among those who spoke. It’s sometimes difficult to follow the thread of what he’s saying, but I found myself struck when he said that the newly ordained pastor had helped him understand how God wants us to make things easier for ourselves, not harder. I commented on it to Gary afterward, how those particular words had constellated like a divine message amid his somewhat disjointed words. “Yeah,” Gary said, “I’ve learned it’s good to pay attention when he talks. That kind of stuff happens a lot with him.”

Make things easier, not harder. The words have been haunting me for weeks now. I am a creature drawn to complication. Given the choice between making the way easy and making the way difficult, I sometimes tilt toward difficulty. I’ve learned my soul often needs to have something to push against, something to forge and form it. I feel kind of like Jacob sometimes; occasionally I need a heated wrestling match with the divine, a struggle that will help me find a new name.

There’s a difference, though, between the complications and complexities that forge the soul and those that drain it. I can wax poetic about the holy disruptions that have deepened me, but I recognize, too, my capacity for choosing complications that stem from some other, less sacred impulse. There are times when I make the way difficult for myself because I’ve taken on too much, or because I’m avoiding something that needs attention, or because I’m giving too much energy to something that I don’t need to be giving that energy to. I recognize that I’m capable of manufacturing my own complications rather than waiting for the ones that come around naturally in traveling with Christ.

So this week’s Gospel lection has given me pause for thought. I’ve found myself particularly chewing on the part where Jesus urges his followers, “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you,” he continues, “and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden light.”

I have to say that it’s long been a challenge for me to buy the notion that Jesus’ yoke is easy and his burden light. I’ve seen a lot of evidence that suggests the contrary. But I wonder if much of the difficulty, heaviness, and exhaustion that we experience in ourselves and that we witness in others comes because we are making our own darn way—and making it difficult—rather than tending our connection with the one who wants to make the way for us and to work alongside us. I wonder if perhaps what Christ meant is not that walking with him is uncomplicated but rather that when we focus on our relationship with him, the road opens before us with less resistance and less striving on our part.

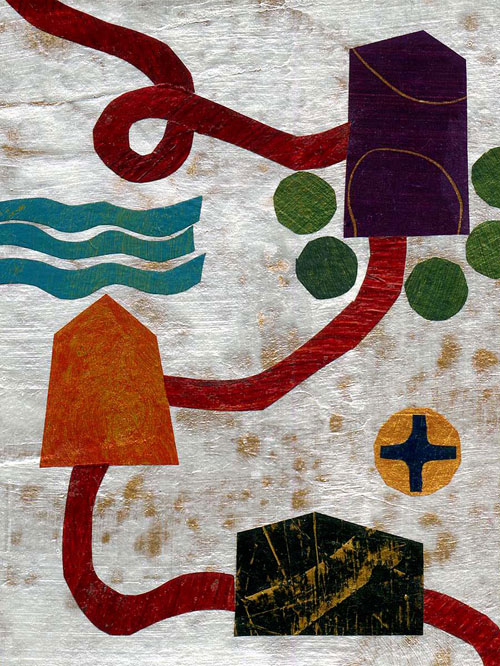

I have to say, too, that I’ve struggled with Jesus’ use of the image of a yoke. On the surface, a yoke connotes bondage, servitude, and the diminishing of freedom and choice. In scanning the Web for images of yokes, however, I realized that I was imagining a single-user yoke, one that someone who has power over us places upon us, something that we have to pull alone. What I found more often on the Web were images of double yokes, designed for working animals to pull in tandem. How might it be to imagine this as the kind of yoke that Jesus was talking about, a yoke that we don’t have to pull alone, a yoke that he wears with us? A yoke not for servitude, not for bondage, but a tool of connection, a way of being in relationship with Christ that makes our work easier, not more difficult.

It’s this kind of relationship, this connection with the Christ who labors alongside us, that makes it possible to go into the complicated realms that our souls sometimes need. This relationship helps us choose between complexity that deepens us and complexity that deadens us. So closely connected with Christ, it becomes more possible to discern how to move in directions that will provide energy and wisdom.

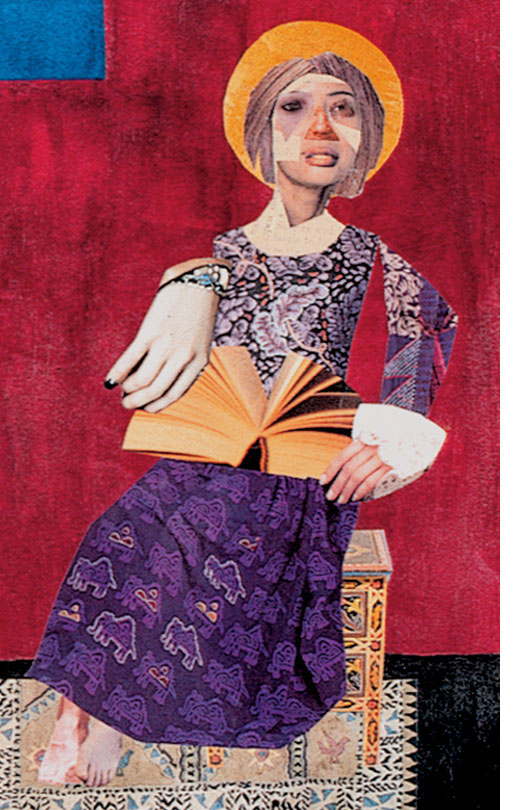

Jesus’ yokeish words find an intriguing resonance in the apocryphal Book of Sirach, also known as Ecclesiasticus. As he describes the Wisdom of God, whom he depicts as a woman, the author of the Book of Sirach writes,

Come to her with all your soul,

and keep her ways with all your might.

Search out and seek, and she will

become known to you;

and when you get hold of her,

do not let her go.

For at last you will find the rest she gives,

and she will be changed into joy for you.

Then her fetters will become for you a strong defense,

and her collar a glorious robe.

Her yoke is a golden ornament,

and her bonds a purple cord.

You will wear her like a glorious robe,

and put her on like a splendid crown. (Sirach 6.26-31)

I don’t know that the yoke imagery will ever sit comfortably with me, but it challenges me to ponder what I’m attaching myself to these days. Truth is, we always bind ourselves, however subtly, to something: people, places, habits, possessions, beliefs, ways of being in the world. What or whom are you yoked to right now? Have you sought these connections, or have you allowed them to be placed upon you by others? Do these connections deepen you or deaden you? Do they draw you closer to Christ or farther away from him? Do they connect you with the power, freedom, and choice that God gives you, or do they diminish your power, freedom, and choice? How might Christ be inviting you to live and work in closer relationship with him?

In your living and your laboring, may you find deep relationship and rest. And a few holy complications.

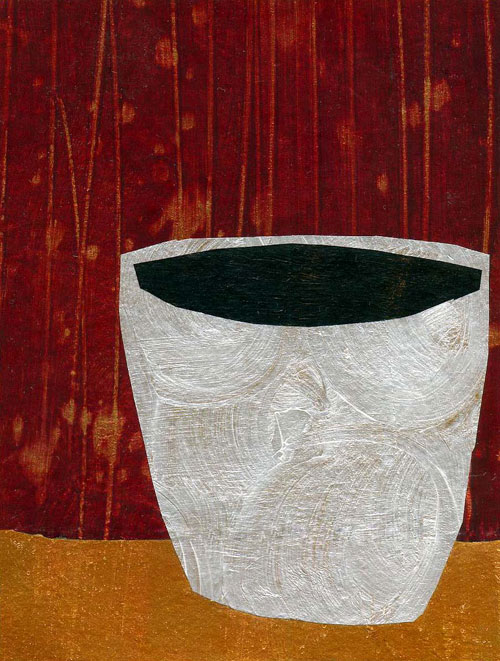

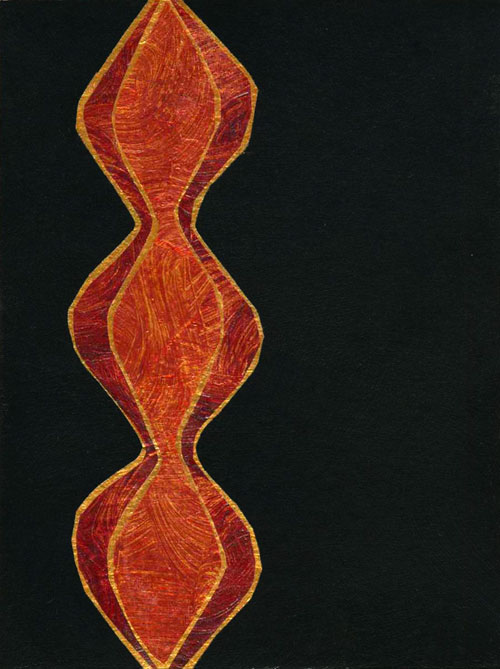

[To use the “If the Yoke Fits” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]