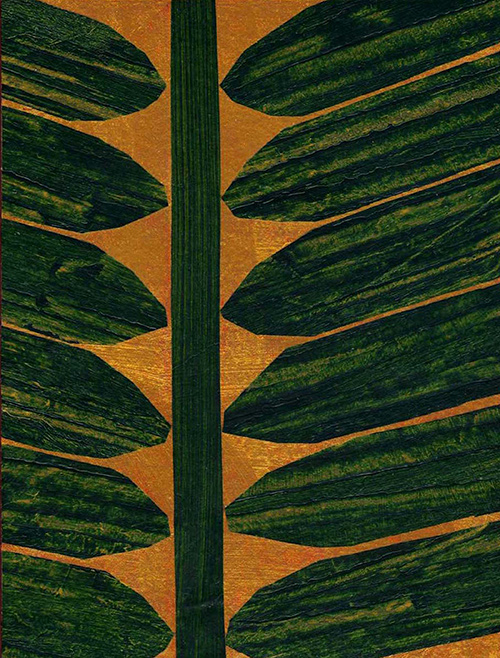

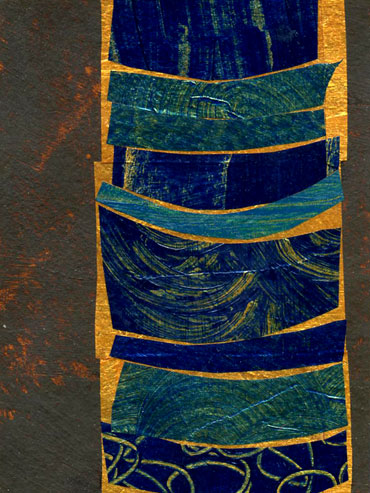

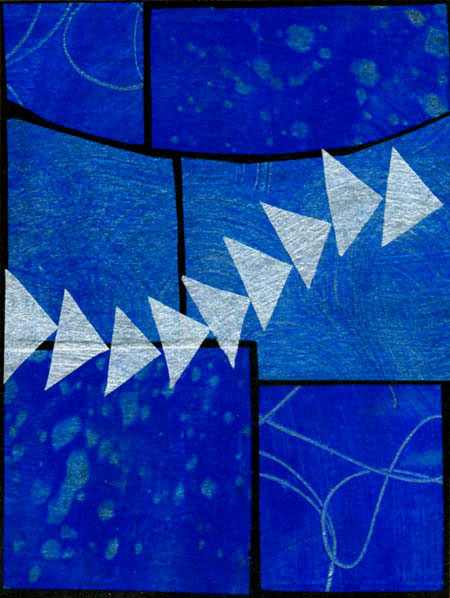

Saint Patrick: Deer’s Cry © Jan L. Richardson

It seems auspicious that Holy Week this year begins with the feast of St. Patrick. Though his feast falls during Lent by happenstance, Patrick offers a powerful example of someone who, in every season, accepted the challenge that Lent poses us: to stretch beyond the familiar borders of the world we know, and to meet God there.

The story of Patrick is deeply entwined with the story of Ireland, so much so that it was only in recent years that I learned that Patrick’s story didn’t begin there. The boy who would become a saint was born in Britain at the end of the fourth century. As a youth he was kidnapped and taken to Ireland as a slave, where he tended flocks and began to spend his time in prayer. In a work titled “Patrick’s Declaration on the Great Works of God,” also known as the Confessio, Patrick writes that as he prayed among the flocks, “more and more, the love of God and the fear of him grew [in me], and [my] faith was increased and [my] spirit was quickened….” After six years, Patrick escaped from captivity and returned to Britain and to his parents, who, he tells us, “begged me—after all those great tribulations I had been through—that I should go nowhere, nor ever leave them.” Yet Patrick goes on to write,

…it was there, I speak the truth, that ‘I saw a vision of the night’: a man named Victoricus—’like one’ from Ireland—coming with innumerable letters. He gave me one of them and I began to read what was in it: ‘The voice of the Irish.’ And at that very moment as I was reading out the letter’s opening, I thought I heard the voice of those around the wood of Foclut, which is close to the western sea. It was ‘as if they were shouting with one voice’: ‘O holy boy, we beg you to come again and walk among us.’ And I was ‘broken hearted’ and could not read anything more. And at that moment I woke up. Thank God, after many years the Lord granted them what they called out for.

Patrick eventually went back to Ireland, returning as a bishop to the land that had been the place of his bondage. For Patrick and his fifth-century contemporaries, Ireland was the edge of the known world. In returning there, he considered himself to be living out Christ’s call to take the Gospel to the ends of the earth. He writes, “We are [now] witnesses to the fact that the gospel has been preached out to beyond where any man lives.” Though Patrick was not the first Christian to set foot in Ireland, he was among the earliest, and his tireless, wide-ranging ministry was pivotal in the formation and organization of the church in that land.

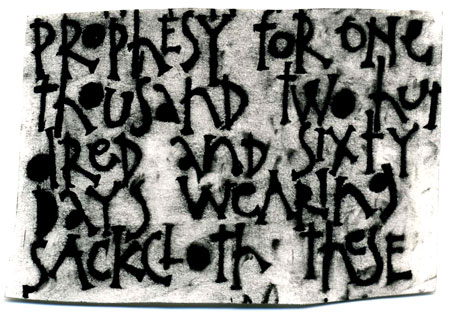

Like all good saints, Patrick has attracted good legends. One story relates that as he and his companions made their way to Tara to see Loegaire, the High King of Ireland, the king’s men tried to ambush them. Patrick sang a prayer, known as a lorica (”breastplate”—a prayer of encompassing and protection), and he and his companions took on the appearance of deer, thereby eluding their attackers. The prayer, which became known as Patrick’s Breastplate or Deer’s Cry, most likely dates to at least two centuries later. It endures, however, as one of the most beautiful and powerful prayers of the Christian tradition, and it conveys something of the spirit of Patrick that continues to permeate Ireland and the world beyond. The prayer reads, in part,

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me;

Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me;

Christ to right of me, Christ to left of me;

Christ in my lying, Christ in my sitting, Christ in my rising…(This excerpt, along with the quotes from Patrick’s Confessio,

come from Celtic Spirituality, translated and introduced

by Oliver Davies.)

Enter “Deer’s Cry” into your search engine and you’ll find a variety of translations of the entire prayer. My favorite translation is by Malachi McCormick of the Stone Street Press. In a charming edition which, like all his books, is calligraphed, illustrated, and hand-bound by his own Irish self, Malachi offers his English translation alongside the old Irish text. I happened upon Malachi’s Deer’s Cry as a seminary student many moons ago and was immediately taken by his elegant and painstaking work. His wondrous books provided the initial inspiration when I founded Wanton Gospeller Press several years ago, and one of my great delights in the wake of that has come in exchanging correspondence with Malachi. I invite you to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day by visiting Malachi’s site at Stone Street Press, purchasing a copy of Deer’s Cry, and picking up a few other books while you’re at it.

A blessed Feast of St. Patrick to you, and may God encompass you with protection on this and all days.

Bonus round: My sweetheart, Garrison Doles, has an amazing song inspired by the life of St. Patrick. It incorporates the ancient prayer of encompassing known as “St. Patrick’s Breastplate” or “Deer’s Cry.” Click this audio player to hear “Patrick on the Water” (from Gary’s CD House of Prayer).

[To use the “St. Patrick: Deer’s Cry” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]