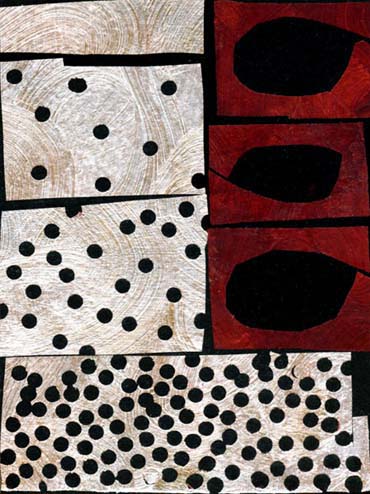

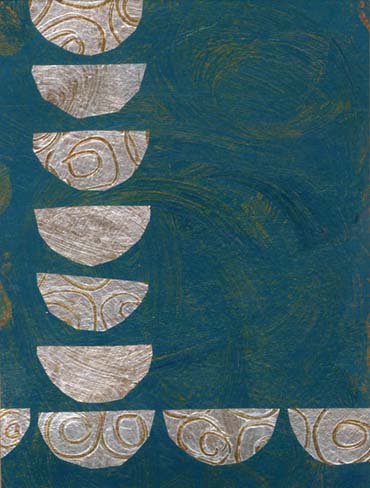

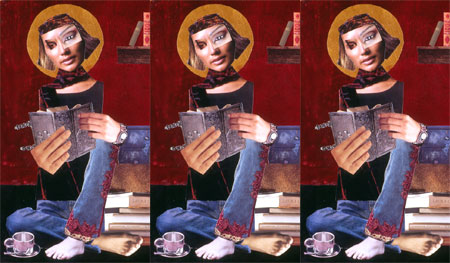

Image: Ash Wednesday © Jan Richardson

Image: Ash Wednesday © Jan Richardson

Recently my sweetheart Gary and I revisited the movie Chocolat, based on the novel of the same name by Joanne Harris. I hadn’t rented the movie with Lent in mind—I actually ordered it during Advent and hadn’t gotten around to watching it—but it offered some tasty images that I’m carrying with me as I cross the threshold into the season of Lent. And by tasty images I don’t just mean Johnny Depp or the stunning sensory overload that Mme. Rochet’s Chocolaterie provides.

Both the movie and the book offer a narrative that beckons us to see the effects of clinging so fiercely to a practice that we miss the point of it. This shines through especially in the figure who appears as the mayor in the film and the priest in the book; his grip on his Lenten fast is ferocious but so fundamentally empty and ungrounded that when he draws near to that which he has resisted for so long, intending to destroy it, he falls helpless before (and in) it. We see a fierce clinging in other characters as well, their lives shaped around practices that keep them insulated and sometimes alienated from one another and from their own selves. For most of the folks in the story, slamming against their beloved walls finally causes them to crumble, opening them to an experience of mercy, reconciliation, and release.

The season of Lent beckons us to see what we are clinging to. The imagery of this season, therefore, is frequently stark. These days draw us into a wilderness in which we can more readily see what we have shaped our daily lives around: habits, practices, possessions, commitments, conflicts, relationships—all the stuff that we give ourselves to in a way that sometimes becomes more instinctual than intentional. Much as Jesus went into the desert to pray and fast for forty days, Lent offers us a landscape that calls us to look at our lives from a different perspective, to perceive what is essential and what is extraneous.

For centuries, the Christian tradition has given us the Lenten fast as a way to gain this perspective. At the core of this practice is a recognition that in giving up something precious to us, we are better able to make room for God. Entering into a spiritual practice, however, always carries the risk that we will become more attached to the form of the practice than to its original intent. Like the priest/mayor in Chocolat, we may become so invested in holding to a certain structure that it insulates us from God and isolates us from other people. Lent challenges us to see and sort through what we are attached to, including our attachments to the practices themselves. Christ’s words in the Gospel reading for Ash Wednesday, Matthew 6.1-6, 16-21, underscore the danger of this kind of attachment. He urges us to remember that being discreet about our practices helps guard against the possibility of becoming overly identified with them or prideful of them.

The desert mothers and fathers—those folks who, in the early centuries of the church, went into the wilderness to seek God—had a keen awareness of the profits and the perils of spiritual practice. In the midst of their earnest desire for God, wise ones among them recognized how seemingly holy habits could sometimes distance them from God and each other. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward, SLG, offers such a story:

Abba Cassian related the following: “The holy Germanus and I went to Egypt, to visit an old man. Because he offered us hospitality we asked him, ‘Why do you not keep the rule of fasting, when you receive visiting brothers, as we have received it in Palestine?’ He replied, ‘Fasting is always to hand but you I cannot have with me always. Furthermore, fasting is certainly a useful and necessary thing, but it depends on our choice while the law of God lays it upon us to do the works of charity. Thus receiving Christ in you, I ought to serve you with all diligence, but when I have taken leave of you, I can resume the rule of fasting again. For “Can the wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them, but when the bridegroom is taken from them, then they will fast in that day.”’” (Mark 2.19-20)

The monks’ host recognizes that in even the most devoted spiritual life, God compels us to root out whatever habit stands in the way of the hospitality to which God calls us.

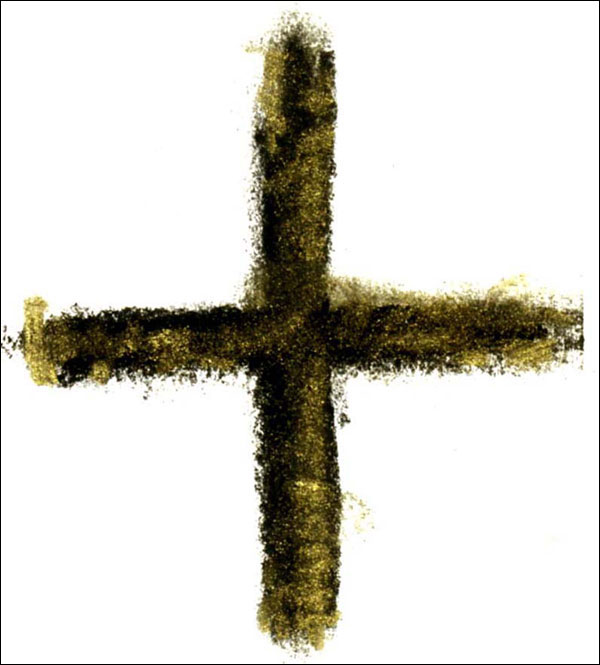

In the ritual of Ash Wednesday, which begins the Lenten journey, we receive a cross-shaped smudge on our forehead. The ashen sign reminds us of what we are fashioned from, and to what we will return. It initiates and impels us into the wilderness where we remember what is most essential to us. It is a dark, stark mark. At the heart of this season, however, is a call to remember that something gleams among the ashes. We do not cling to the ashes for the sake of ashes, nor to the wilderness, nor to the outer form of whatever practice God gives us. Lent beckons us to cling to the one who dwells within and beneath and beyond every ritual and practice and form: Christ our Light, who desires us to receive his hospitality even—and perhaps especially—among ashes.

What habits are you shaping your life around? Which of your habits are instinctual, and which are intentional? What do you feel drawn to practice in the coming season? As you engage in that practice, what will help you stay focused on the purpose of the practice, so that it will remain a doorway to God, rather than becoming a wall?

A blessed Shrove Tuesday/Fat Tuesday/Mardi Gras to you today, and traveling mercies as we head into the landscape of Lent.

[To use the “Ash Wednesday” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of the Jan Richardson Images site helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]