Fulfilled in Your Hearing © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 3, Year C (January 24): Luke 4.14-21

In doing research for my new book, two of the most intriguing women I encountered were Agnes Smith Lewis and Margaret Dunlop Gibson. Twin sisters born in Scotland in the 19th century, Agnes and Margaret were a formidable pair who became pioneering scholars and explorers in a time when this was a rare feat for women. Semitic languages and biblical studies became their particular passions, and in 1892 they traveled to Egypt to make their first visit to St. Catherine’s Monastery. Established in the sixth century at the foot of Mt. Sinai, the Greek Orthodox community is famed for the many treasures it holds from the early centuries of Christianity. Margaret and Agnes hoped to study some of the ancient manuscripts in the monastery’s library.

Agnes writes that among the ancient books placed into their hands by the librarian of St. Catherine’s was “a thick volume, whose leaves had evidently been unturned for centuries, as they could be separated only by manipulation with the fingers…” In some cases, they had to separate the leaves with a steam kettle.

Agnes recognized the book as a palimpsest, a manuscript whose text had been effaced and overlaid by a later text. Such a practice was common in times when vellum was scarce. Looking closer, she saw that the more recent text was, as she described, “a very entertaining account of the lives of women saints.” Thecla, Eugenia, Euphrosyne, Drusis, Barbara, Euphemia, Sophia, Justa, and others: women revered in Eastern Christianity, these were among the desert mothers, women of the early centuries of the church who gave up safety, security, convention, and finally their lives in order to follow Christ.

Looking closer still, beneath the stories of these women saints, Lewis recognized that the more ancient writing belonged to the gospels. The manuscript proved to be what was then the oldest Syriac version of the four gospels, dating to the fourth century. It was a stunning discovery.

Reading about the palimpsest, I found myself fascinated by the imagery present within its story. The pages of the manuscript, with their layers of text, make visible what happened in the lives of these women of the early church. By their devotion, by their dedication to preserving and proclaiming the gospel message, the desert mothers became living palimpsests, the story of Christ shimmering through the sacred text of their own lives, the Word of God fulfilled in them.

I have thought of these women and this story in pondering the gospel reading for this Sunday. Luke tells us that, fresh from his forty-day sojourn into the wilderness and filled with the power of the Spirit, Jesus begins to teach in the synagogues. Coming to Nazareth, the hometown boy stands and reads from the scroll of Isaiah. From his lips flow some of the most powerful words in all of scripture:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim

release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. (Luke 4.18-19)

Finishing his reading, Jesus rolls up the scroll, returns it to the attendant, and sits down. One can imagine him pausing for dramatic effect before he then says to his listeners, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

It is perhaps the shortest teaching the crowd has ever heard. Not to mention the most startling, and, as we will see in next week’s gospel lection, one that will turn deeply disturbing.

The text doesn’t say whether his mother, Mary, was there, but I can imagine her listening to Jesus, a small smile on her face as she takes in the words of his reading and teaching. She is the woman, after all, who had sung words much like these when she carried this child-now-man inside her: had sung of a God who scattered the proud and brought down the powerful, a God who lifted up the lowly and filled the hungry with good things. From the womb Jesus had been marked by radical words about this God who showed mercy from generation to generation and was about the business of turning the world right side up. Like his mother, whose song was an echo of one sung by her foremother Hannah, Jesus offered words with a history, lines that were rooted in an ancient hope.

Amongst the crowd, his mother is perhaps the only one unsurprised by the stunning message from the lips of this One who was so deeply imprinted with the liberating words of God. And not just imprinted with those words, not just a vessel of those words, but the Word itself, the Word made flesh, the One who incarnates the Word in his own being. On that day in the synagogue, Jesus comes among them as the sacred story of God embodied in fullness for all to read; the ancient, sacred texts cohering and taking form and coming to life in him, for the life of the world.

And we who are the body of Christ and followers of the Word: what will we do with these words about good news for the poor, release for the captives, sight for the blind, freedom for the oppressed, and the year of God’s favor? How do we, like those long-ago desert mothers, let these ancient words show through the lines of our own lives? How do we, like the Christ whom we follow, give flesh to these words? Amid the brokenness of the world—of which we have been reminded so vividly by the devastation in Haiti—how do we become bearers of these words that are so radical and so challenging in the hope to which they call us?

These are a few of the questions that I—a woman in love with the Word and with words and who cannot rightly extricate the latter from the former—am chewing on in these days. May these words—the words of Isaiah, the Word of Christ—challenge us, call us, enliven us and take flesh in us, for the life of the world. Blessings to you.

Note: Agnes Smith Lewis’s account of the finding of the palimpsest is from her book, available online, A Translation of the Four Gospels from the Syriac of the Sinaitic Palimpsest. Janet Soskice has recently published a lively and absorbing book about Agnes and her sister Margaret; I highly recommend The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Found the Hidden Gospels.

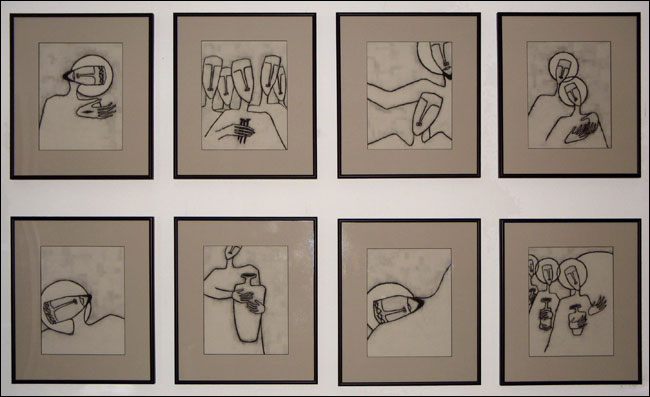

[To use the “Fulfilled in Your Hearing” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of the Jan Richardson Images site helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

A Couple More Things…

Coming Attractions: Now that the book is (mostly) finished, I’m moving back into a rhythm of offering periodic retreats and workshops. I’m looking forward to traveling to Minnesota, Virginia, and Washington State in the next few months and invite you to stop by my just-added Upcoming Events page to check out what’s ahead.

Prints & More Prints: All the images here at The Painted Prayerbook and also at The Advent Door are now available as art prints! Visit Jan Richardson Images, go to any image that you’d like, and scroll down to the section that says, “Order as an Art Print.”

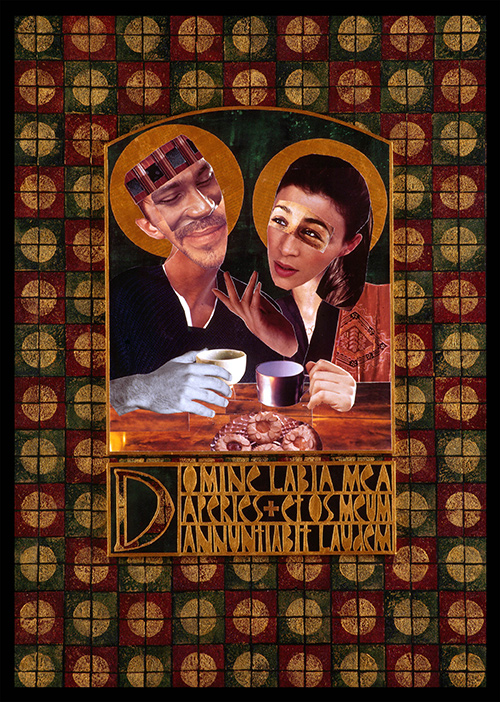

Image: The Blessing Cups: Mary Magdalene and Jesus at Tea

Image: The Blessing Cups: Mary Magdalene and Jesus at Tea