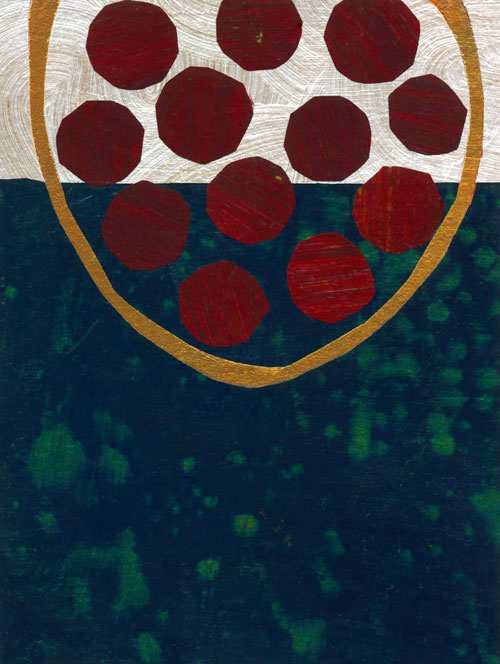

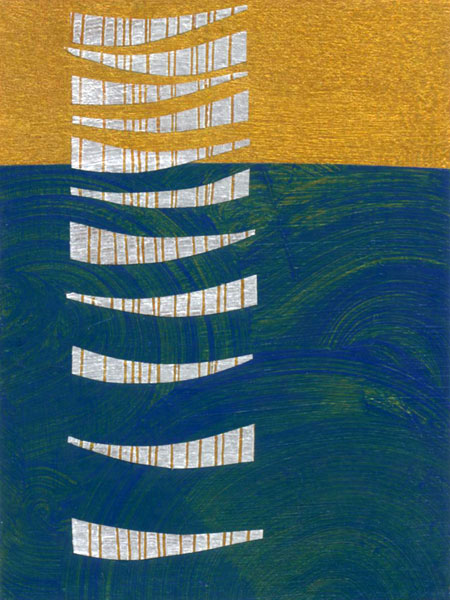

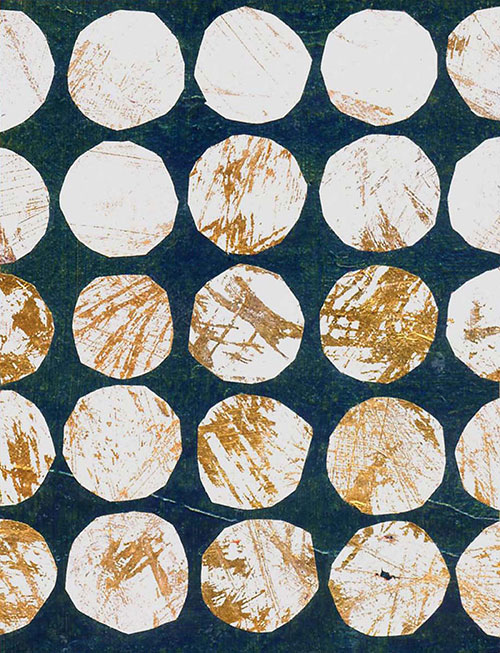

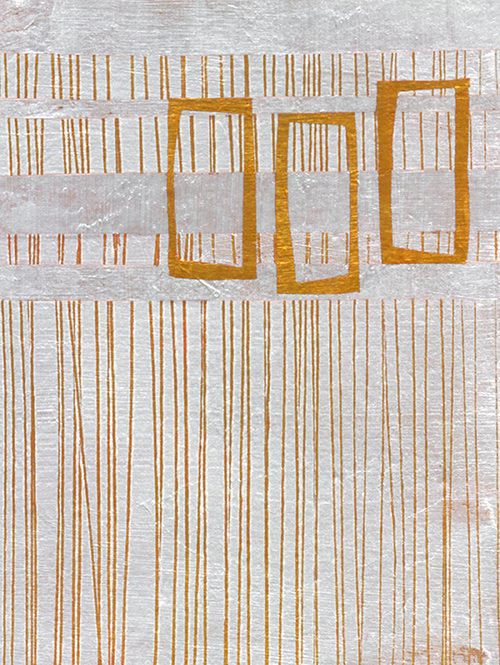

Image: Transfigure © Jan Richardson

Image: Transfigure © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Transfiguration Sunday, Year C:

Luke 9:28-36 (37-43)

I was nearly finished with the collage before it occurred to me that the design perhaps owes as much to the snow I was recently in as it does to next Sunday’s gospel text. Gary and I have returned from Minnesota, and although we (and they) joked about the wisdom of importing Floridians at this time of year, it was a great gift to be in a lovely winter’s landscape and to receive wondrous hospitality as we shared a morning at Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church (including a worship service that takes place in their art gallery, what a concept) and in events at Wisdom Ways Center for Spirituality and United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities.

At the events, I had occasion to share images of some of my artwork from the past 15+ years. It was the first time I had brought these images together in quite this way, from early work such as Wise Women Also Came (made when I was still using construction paper!) to the more recent collages I’ve created for this blog and The Advent Door. Looking back over this body of work prompted me to do some reflecting on how my style has changed. Although paper collage remains my first love, my technique and my style have both shifted considerably, taking an increasingly abstract turn since I began creating artwork for my blogs more than two years ago.

When it comes to the creative process, I can’t say I have a lot of control. Trying to wield too much control, in fact, is one of the worst things an artist can do (which doesn’t always keep me from trying). I didn’t exactly set out to do abstract work. The technique, which involves painting tissue paper, emerged from creative necessity as I was working on The Welcome Table: the scale was so large (4.5 x 6.5 feet) that I couldn’t snip the characters’ clothes out of magazines; I had to fashion them myself. I can’t explain the ensuing turn toward abstraction, except in part: once the painted papers showed up, that’s the path they took me down. That, and these lectionary texts that take me to places that so often resist traditional depictions. I experience abstract art as being more like poetry in the space that it creates. “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant,” Emily Dickinson wrote. I’m not trying to explain these passages, but to evoke, to invite, to sidle up alongside the texts and offer a doorway into them amidst line and shape and color.

Along the way, what I keep working and hoping to do is to give myself to the mysteries involved in the process of making: to pay attention to what emerges among the papers and to follow where they lead; to keep clearing out a space within myself that leaves enough room for something new to show up; and to avoid growing so attached to a particular style or technique that it becomes overworked and ossified.

In my artful work and elsewhere, the challenges that the disciples encounter in this passage from Luke are my own challenges. Like Peter, John, and James at prayer with Jesus on the mountain, I sometimes struggle to stay awake when it’s easier to be lulled into sleep and to miss the thin places, the meetings of heaven and earth, that open up in the midst of daily life. And when those thin places come—when a burst of inspiration opens a new world, say, or, after hours or months or sometimes years of experimentation, something finally comes together at the drafting table, and both the work and I myself are transformed—it can be tempting to want to set up shop there, to preserve the moment, as Peter longed to do. I recognize his impulse in my own self, his desire to want to linger in the wonder. And why shouldn’t he? Yet the persistent invitation of Jesus is to take what we have seen, what we have found, down into the trenches of everyday life.

It’s not a new message; I’ll wager that the greater percentage of the sermons preached on this text will offer a variation on the theme of navigating the transition from the mountaintop to the flatlands. And yet we need to keep practicing that transition, to keep rehearsing the journey that moves us from being recipients of wonder to becoming people who, transformed and—shall we say it?—transfigured by what we have received, can then offer these wonders to a broken world.

When the disciples come down from the mountain, they still have plenty of struggles ahead. They’ve hardly gotten their feet back on flat land when, Luke tells us, they encounter, and fail to heal, a boy in the grip of what Luke describes as an unclean spirit. In juxtaposing the stories, Luke suggests that the disciples’ own spirits are still struggling between holding on and letting go, are still struggling to leave a space for the wonders that Christ seeks to do within and through them. It will take rehearsing, and practicing, and rehearsing some more. In my own life, cultivating this space is something that, quite literally, I keep going back to the drawing board to learn.

This is a great passage to lead us toward Lent, a season that is all about discerning what it is that we cling to, and what we need to practice letting go of in order for Christ to become more clear in us. But Lent will come around soon enough. In the meantime, where does the story of Peter and John and James connect with your own? How are you navigating the journey that their own feet trace between the mountaintop and the flatlands? What do you find yourself tempted to cling to, and how do you practice letting go of it? Do you have habits and spaces that invite you to cultivate an openness to the new ways that God desires to work in and through you? Where and how do you rehearse the transfiguration that God seeks to bring in your life?

As we move toward Transfiguration Sunday, may we keep awake to the wonders in our midst, let ourselves be transformed by them, and follow the path they open to us. Blessings.

[For an earlier reflection on the Transfiguration, please see Transfiguration Sunday: Show and (Don’t) Tell. To use the image “Transfigure,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

Update: Speaking of the creative process, the very cool site patheos.com has recently reprinted an interview that Christine Valters Paintner did with me at her also-very-cool Abbey of the Arts, in which she invited me to reflect on my practice as an artist. Here’s the reprint at Patheos: Sacred Artist Interview: Jan Richardson.