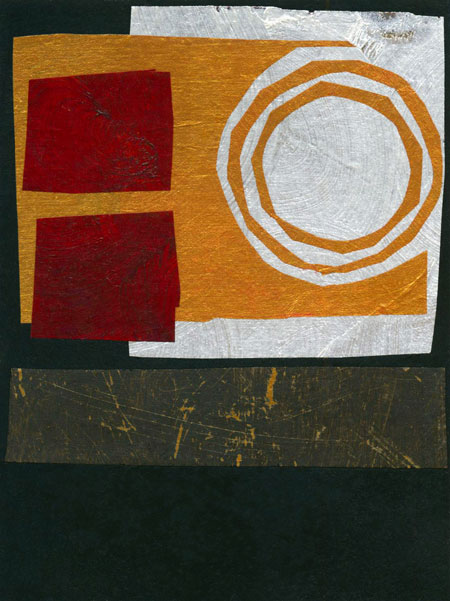

Where God Grows © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 21/Ordinary 26/Pentecost +15: Matthew 21.23-32

My sweetheart Gary and I spent much of this past week leading a retreat for a wondrous group of folks who were recently commissioned as ministers in the Florida Conference of the United Methodist Church. The retreat took place in Lake Wales at Bok Tower and Gardens, a piece of paradise about an hour and a half south of my home. I hadn’t been there since I was a young child. The first couple of days, I had a vague awareness that something seemed enchanting and familiar about the landscape in that part of the state. Then it struck me: it was the orange groves.

I grew up in north central Florida, in a small community that has preserved the landscape of “old Florida” in a fashion that has become rare. I’m a native Floridian several generations over; my great-grandfather was one of the settlers of the town I grew up in. With his sons he established a farm that remains in operation, and that has helped the town to preserve its rural landscape.

For decades, citrus was one of the mainstays of the farm, and it pervaded the culture of that region. Acres of groves stretched through my hometown and the surrounding area. Just to the south of us were groves whose owner had a citrus shop on the highway that looked out over Orange Lake. (A sign outside the shop proclaimed, “See the famous red bats!” Walking a little way into the grove by the shop, one would come to a small cage that contained…two red baseball bats.) At Silver Springs, a longtime attraction in nearby Ocala, the gift shop offered a plethora of citrus-related items, including pottery infused with the scent of orange blossoms.

Navel oranges were my favorite, and winter always found a bag or two of them stashed outside our back door, staying cool through the season. Fresh orange juice made frequent appearances at our breakfast table, and I loved it when Dad would take a sharp knife, peel an orange and slice it in half for me, and I would sink my teeth into its flesh.

Winter also brought the threat of freezing temperatures and the call that would come late at night, summoning all hands to fire the groves. Too young to join in, I envied my older sister and brother who got to participate in what I imagined to be the excitement of lighting the kerosene heaters that preserved the trees in those freezing nights. I assumed there would be a time when I would be old enough to go.

In the 1980s, a particularly bad freeze hit the groves. The heaters were not enough. We lost the trees, and the landscape of my hometown was forever altered. At the time, I had little awareness of what a loss it was. But these days I miss the presence of the flourishing groves. Even here in Orlando, located in “Orange” County a couple hours south of my hometown, citrus groves are hard to come by, many of them having given way to housing developments. Still, memories of the groves of my childhood linger in my imagination. Visiting Lake Wales this week stirred those memories, conjuring that landscape both real and mythic where the roots of my history remain.

My experience of those citrus groves helps me grasp the presence of the vineyard in next Sunday’s gospel lection. Matthew 21.23-32 is the second in a series of three lections containing parables about vineyards. The repetition got me intrigued and set me to pondering the place of the vineyard not only in this section of Matthew’s gospel but also in the whole of scripture. What is it that Jesus is calling upon here, in his repeated use of this image as a dramatic setting for his storytelling?

In Jesus’ time, the vineyard held a place in the culture that was not only real, being so prevalent in the landscape in that part of the world, but also mythic; it tapped into the people’s collective imagination with a constellation of meanings and associations. In the Bible, vines and vineyards stand for the people of Israel, as in Psalm 80, where the psalmist writes of how God brought a vine out of Egypt, and Isaiah 5, where, in a passage called “The Song of the Unfruitful Vineyard,” the prophet laments, “For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel, and the people of Judah are his pleasant planting; he expected justice, but saw bloodshed; righteousness, but heard a cry!” Vineyards can be a place of danger; Judges 21 offers the chilling story of how men of the tribe of Benjamin hide themselves in the vineyards of Shiloh, emerging to capture the young women who have come out to dance, and carrying them off as wives. And vineyards are a place of delight, which is nowhere as evident as in the Song of Songs: “Come, my beloved,” the bride sings in chapter 7, “…let us go out early to the vineyards, and see whether the vines have budded….”

The vineyard offers elemental metaphors of fertility and fruitfulness. It is, at times, a profoundly feminine image, as in the Song of Songs, where it becomes identified with the bride’s own body. The vineyard is a place where both labor and love take place. Though it may be a place of harm, as we will see with particular clarity in next week’s gospel lection, it is a space where right relation becomes possible, as evidenced between the lovers in the Song, between God and the people of Israel, and, as we will see in John’s gospel, between Jesus and his followers (“I am the vine, you are the branches”).

For Jesus’ hearers, the vineyard grew not only in the landscape of their daily lives but also in a mythic landscape that stretched back for generations: the book of Genesis tells us that Noah was the first to plant a vineyard. Its tendrils also twined forward into a future where redemption would take place: “I will restore the fortunes of my people Israel,” God says in Amos 9.14; “…they shall plant vineyards and drink their wine….”

In setting this trio of parables in vineyards, Jesus subtly conjures all these associations. Though his hearers likely would not have consciously thought of each of these layers of meaning as he told these stories, the fact that the image of the vineyard was deeply embedded in their personal and collective memory would have shaped their reception of these parables.

All this has me wondering about how we hear the parables of Jesus in a context where so many of us live so distant from the settings that grounded his stories. I’ve spent little time in vineyards, save for the small bower of muscadine and scuppernong grapes that grew in my grandparents’ yard. Having grown up among the groves, however, I can appreciate how a landscape roots itself in one’s imagination, how it intertwines with personal and shared history, how it can be so easily evoked decades later, how it helps me enter into certain stories.

How do we hear these sacred stories that are rooted in an agrarian landscape that fewer and fewer of us inhabit? How do we receive the imagery of the Bible when we are cut off from so many of the sources that imbue those images with meaning? Think of them: not only vineyards, but also pastures, flocks, wellsprings, gardens, fields. And not only agrarian images, but other images as well that speak to what it means to be community together. What does the idea of church as a household mean, when home life for many folks is a fragmented experience? And what does the table of Communion conjure, when families eat in shifts as their schedules demand, or when we eat alone?

It would be easy, perhaps, to slide into a rant about how we’ve lost the sources that nourish our imagination, to lament how so much of our 21st century culture has divorced itself from the landscapes, both real and metaphorical, that cultivate a mythic memory. I’m not particularly interested in ranting here (though I’m not above tilting into a good one once in a while). I’m more interested in asking questions about how we in the church work to create spaces and rituals that cultivate the imagination, that nourish and call on our collective memory, that lay down the layers of sensory experience that help us connect with the sacred stories our tradition gives us.

I am alarmed by churches that, in an attempt to be welcoming to newcomers, strip their spaces of the symbols and rituals that link us to our shared story. I understand and affirm the desire to create a hospitable space for those who are unfamiliar with the terrain, but I don’t think we do this best by erasing the environment that helps evoke the stories.

We don’t tell the story well by trying to be overly efficient about it, either. I was talking recently with someone who lamented how her church rarely celebrates Communion, out of a belief that there’s “not enough time” to give to this central ritual that, when well done, engages every one of our senses, and thereby takes hold of us in a way that hearing alone, or seeing alone, cannot.

In a culture where so many of us are separated from the experiences and images that imbued Jesus’ hearers with understanding, our church communities can be places that provide other kinds of experiences that still link our senses, our memories, and our imaginations with our sacred texts. How do we draw one another into the mythic spaces that the scriptures offer? How do we ground one another’s hearing and reading of these scriptures in experiences that involve our seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting? How do we cultivate a landscape that lingers in the memory like a vineyard, a grove, a space that, decades later, can still conjure a connection with the Divine who dwells both in the imagination and in daily life?

In telling this parable about the father who asks his sons to work in the vineyard, Jesus makes the poetic and prophetic point that the kingdom of God is open to all, including those whom many of Jesus’ hearers would have considered unworthy: prostitutes, tax collectors. He insists that even—and especially—those who have spent most of their lives pursuing other intentions belong in this space of redemption, relationship, fruitfulness, and delight. For all its seeming orderliness, the vineyard is a place of God’s wild grace. Perhaps only those who know the deep, unsated hunger that the world instills can ever, finally, understand and receive that.

In our 21st century world, how do we convey this kind of grace that God extends to all? How do we describe and evoke the ways that God calls us to give ourselves not only to the labor but also the delight that the image of the vineyard conjures? How does this parable resonate in your own memory and imagination? With what images, practices, and rituals do you invite others to connect with our sacred stories?

These aren’t rhetorical questions; I’d love to hear how you do this, or how you long to. It seems an especially fruitful time to ponder these questions in this month when, in the northern hemisphere, the harvesting of wine grapes is taking place, often accompanied with festivals. (The fact of which gave rise to September’s full moon being known as the “Wine Moon” in some quarters.) In this season, may the wild grace of God make itself known through all your senses. Blessings.

[To use the “Where God Grows” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

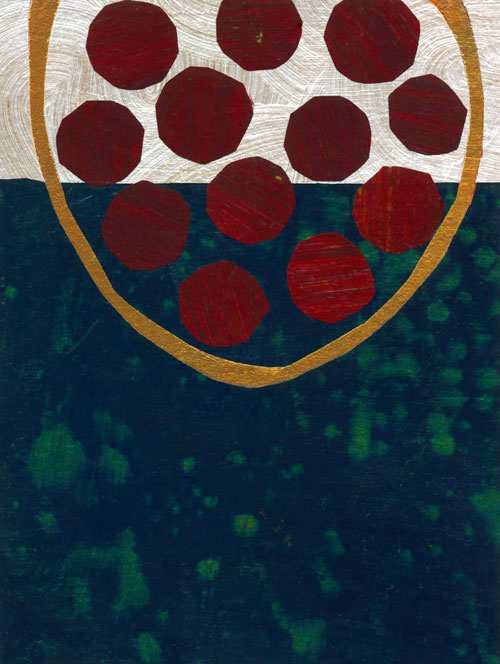

Image: A Gracious Plenty © Jan Richardson

Image: A Gracious Plenty © Jan Richardson