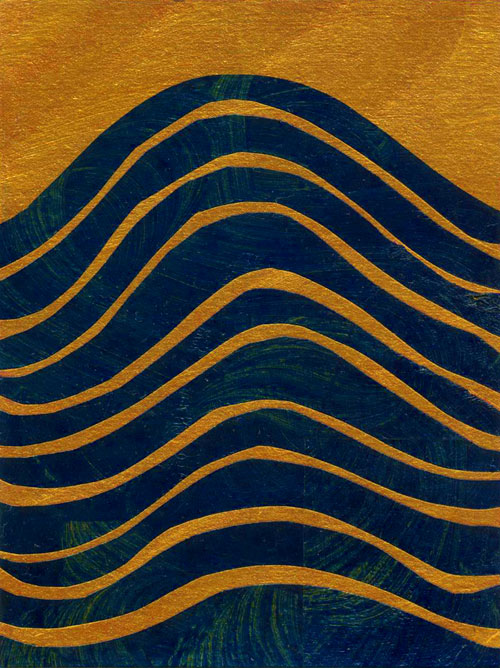

Image: The Serpent in the Text © Jan Richardson

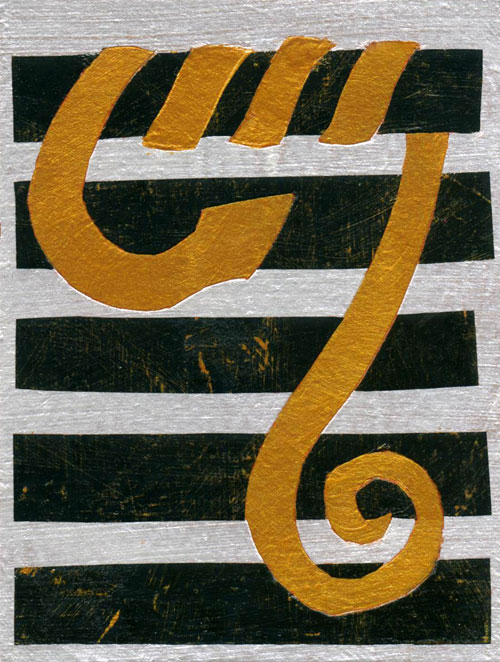

Image: The Serpent in the Text © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Lent 4, Year B: John 3.14-21

One evening a bunch of years ago, I found myself in a New Zealand coffeehouse with some friends I was traveling with. We were there with a friend whose presence in New Zealand had occasioned our trip, plus that friend’s flatmates. It was a wonderfully funky coffeehouse, and as we settled into the couches and chairs with cups in hand, I commented, “Hey, it’s just like Friends!” One of my companions commented that she’d recently read that one of the indicators of contemporary culture was the rising frequency with which we compared our lives to television shows. And this was the 90’s; so-called reality TV, with its further blurring between life onscreen and off, had barely made its appearance.

The comment didn’t cause me to stop watching Friends, but it did set me to noticing the referents I use when I tell something of my life, or hear others use in telling about theirs. Ever since that New Zealand coffeehouse evening, I’ve found myself watchful of what we hook our stories onto, and how we locate ourselves within our cultural landscape.

So I could hardly get past the way that Jesus does this from the opening sentence of the gospel lection for next Sunday. The passage begins in the midst of Jesus’ nighttime conversation with Nicodemus. “And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness,” Jesus says to Nicodemus, “so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him might have eternal life.”

Jesus, like a serpent in the wilderness? Hunh?

That’s quite the referent that Jesus inserts into their chat, a potent image that he brings into a conversation already drenched with symbolism and metaphor. Jesus and Nicodemus have been talking, after all, about being born again, with its attendant imagery of birthing, water, womb, spirit, and wind.

Being a good Pharisee, however, Nicodemus would have known the snaky reference. It comes from Numbers 21.4-9, which serves as the lection from the Hebrew Scriptures for Sunday. Frankly, it’s a right bizarre tale, and steeped in a few layers of magical lore. In it, we find the people of Israel in the wilderness. They have been delivered from their captivity. And they are complaining. “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt,” they cry to Moses, “to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we detest this miserable food.”

On a similar occasion in the book of Exodus, God hears the complaints of the people and rains down manna upon them.

This time, God sends fiery serpents. Or, depending on the translation of the Hebrew word seraphim, God sends poisonous serpents. Or winged serpents.

Whatever they are, they aren’t good.

And the serpents bite the people.

And many of the people die.

And the people are very, very sorry.

They come to Moses, full of remorse for being grumbly, and they beg him to pray to God to take the serpents away. Moses prays. In a curious move, God does not take the serpents away. Instead God sends a strange remedy. God tells Moses to make a fiery serpent—or a poisonous serpent, or a winged serpent; whatever it is, Moses makes one out of bronze. As God has told Moses, whenever a serpent bit someone, that person could look at the bronze serpent and live.

Did I mention it’s a strange tale? It’s a little tempting to wade a bit further into the mythological waters that gave rise to this piece of the story. For now, however, let’s just say that part of its point is this: the people are saved by seeing. When the fiery/poisonous/winged serpents come among them, those who succumb to snakebite know where to turn their attention, and thereby live.

In his conversation with Nicodemus, Jesus accrues this meaning to himself. Look on me and live, he says. Turn your gaze, your attention, your focus to me, and you will be saved by the hand of the God who sent me, not for the punishment of the world but for the utter love of it.

The imagery that Jesus offers Nicodemus could hardly be more potent in our own time. Amid the perils of the present, amid the terrors and dangers, God in the main chooses not to remove the hazards from us but continues to provide a remedy for us. In the person of Jesus, God put on flesh and came not only to walk among the dangers with us but also to help make a way through them.

Jesus’ words in this passage prompt me to ponder, where am I turning my attention these days? How do I seek to do what Jesus invited Nicodemus to do: to turn my attention, to turn my gaze toward him—not merely to escape punishment, but as my response to the love that impelled God to send us Christ?

Those questions alone would be enough to carry me through the rest of Lent, a season designed to help us discern what we’re giving our attention to. Yet Jesus’ reference to the snaky tale in Numbers prompts me to ponder, too, where I’m turning not only my attention but also my imagination these days. The presence of the serpent in the text beckons us to attend to the mythic matrix out of which the story of Jesus arises.

If we know Jesus only from reading the New Testament, we’re missing entire layers of meaning. The early hearers of the Jesus story—those who were familiar with the Hebrew scriptures—encountered and understood him in the context of the symbols, images, and metaphors upon which he drew. As we find in next Sunday’s text, those images can take us down some strange paths, to be sure. But they tug at and feed our imagination in crucial ways, telling us what words alone cannot convey.

The metaphors, images, and symbols that slither through our sacred texts beckon us also to consider what we steep our imaginations in—not only within the scriptures but also beyond them. In a culture in which our conversational referents tend to fit within a fairly narrow patch of common ground that’s dominated largely by television and other electronic media, how do we feed our imaginations—and our souls—with the things that will bring richness and depth?

I’m not going to give up the occasional episode of Friends, or the other shows that provide a break for a brain that spends probably way too much time pondering and processing and thinking about stuff. In these Lenten days, though, I’m going to give some thought to where I’m turning my attention and imagination, and to how Jesus calls me not only to turn them toward him, but also to the widespread wonders in which he can be found.

Where are you turning your gaze these days? What are you steeping your imagination in? What are you giving your eyeballs, your mind, your soul to? Stories, images, metaphors, poetry, art: what is the culture that you are creating and participating in, or long to be? How does this help you encounter the incarnate presence of the God who came solely for love of you?

A blessing upon your eyes this week, that you will find wonders along the way.

[To use the image “The Serpent in the Text,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

Resources for the Season: Looking toward Lent