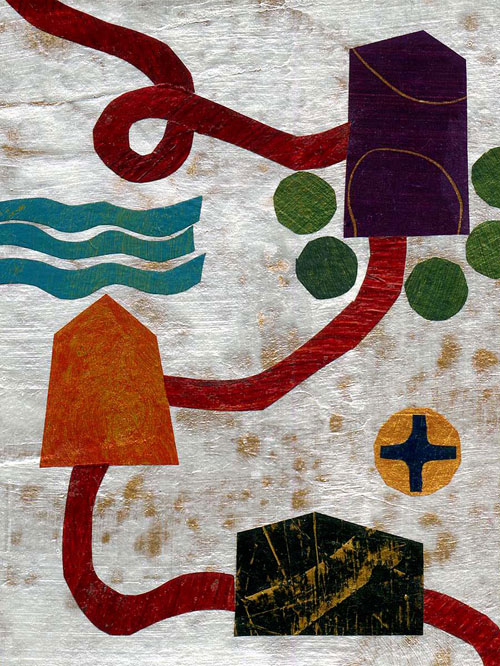

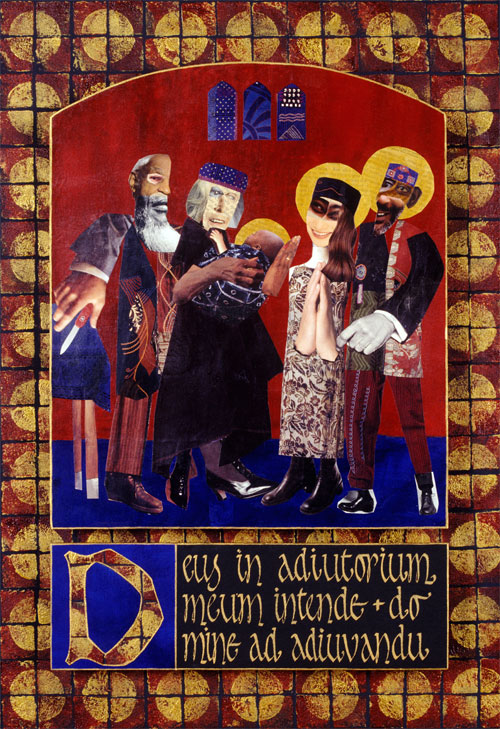

The Humble Seat © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Proper 17/Ordinary 22/Pentecost +14, Year C (August 29): Luke 14.1, 7-14

Ah, the endless wisdom of the table! Throughout Jesus’ ministry, we see again and again how in much the same way that he never passes up an opportunity to share a meal with others, he rarely misses the chance to use a table as an occasion to teach. Whether it’s welcoming a woman who anoints him, or using the table as a way to talk about the kingdom of God, or employing the elements of a meal to describe who he himself is: the table, for Jesus, is always about right relationship, about how we are to live in community and communion with one another.

At the table that Luke tells of in next Sunday’s gospel lection, Jesus turns his attention not only to the kind of hosts we are to be—inviting those who owe us nothing—but also to the kind of guests we ought to be. When we receive an invitation to share in the table of another, Jesus says (a wedding banquet, in this case: Jesus’ ultimate image of the kingdom of God) we should come with no expectations, no intent to grasp at a seat of honor—from which, Jesus says, we might be ejected. When approaching the table, Jesus says, our stance, is to be one of humility, a posture that leaves room for surprise and for grace.

When it comes to humility, and discerning how we are called to embody this sometimes perplexing quality as the people of Christ, I often find myself turning back to the desert mothers and fathers, those ammas and abbas of the early church who articulated this disposition with such clarity. Of all the practices and habits that these early Christians engaged in, humility was the one that surpassed all others, and upon which all other practices depended. We see this, for instance, in Amma Theodora. In The Sayings of the Desert Fathers we read that Amma Theodora said, “Neither asceticism, nor vigils nor any kind of suffering are able to save, only true humility can do that.” She went on to say, “There was an anchorite who was able to banish the demons; and he asked them, ‘What makes you go away? Is it fasting?’ They replied, ‘We do not eat or drink.’ ‘Is it vigils?’ They replied, ‘We do not sleep.’ Is it separation from the world?’ ‘We live in the deserts.’ ‘What power sends you away then?’ They said, ‘Nothing can overcome us, but only humility.’ ‘Do you see how humility is victorious over the demons?’” Amma Theodora recognized that without humility, all our practices become hollow.

The desert folk, however, understood humility in a rather different way than we tend to in the 21st century. Where we sometimes equate humility with being a doormat, Roberta Bondi points out in her book To Love as God Loves: Conversations with the Early Church that “humility did not mean for them [the ammas and abbas] a continuous cringing, cultivating a low self-image, and taking a perverse pleasure in being always forgotten, unnoticed, or taken for granted. Instead, humility meant to them a way of seeing other people as being as valuable in God’s eyes as ourselves. It was for them a relational term having to do precisely with learning to value others, whoever they were. It had to do with developing the kind of empathy with the weaknesses of others that made it impossible to judge others out of our own self-righteousness.”

At the root of humility is the Greek word humus. Earth. The earth that God made and called good, the earth from which, as one of the creation stories goes, God fashioned us. Humility is our fundamental recognition that we each draw our life and breath from the same source, the God who made us and calls us beloved. Humility does not only prevent us from seeing ourselves as more deserving or graced or better than another. It compels us also to recognize that we are no less deserving or graced than another. For women, so often conditioned to take on roles and attitudes of subservience, this is a particular point that the desert teachers would have us understand. Humility draws us into mutual relation in which we allow no abuse, no demeaning, no diminishment of others or of ourselves.

And when we bungle it, or see others bungle it, humility gives us a break. “When it comes to living together,” Bondi writes in her book To Pray and to Love, “humility is the opposite of perfectionism. It gives up unrealistic expectations of how things ought to be for a clear vision of what human life is really like. In turn, this enables its possessors to see and thus love the people they deeply desire to love.”

Humility invites us to stay low to the ground so that we can find the treasures there. Not so low that we become a doormat, subject to whatever treatment others may mete out to us. Instead, humility helps us remain grounded in the best sense of the word: centered in the humus from which we have been created, the gloriously ordinary earth from which God made each one of us. Humility enables us to recognize our dependence on the One who fashioned us as well as our kinship with those who share this earth, this humus. In practicing humility, we leave room for the surprising and graced ways that God works—beyond expectation, beyond privilege, beyond status—at the table and in every place beyond it.

So how’s your humus these days? In what are you centering and grounding yourself—your earth? Are you leaving God enough room to work beyond your expectations and assumptions? How might God be challenging you not only to offer hospitality but also to receive it in ways that bring wholeness?

Blessings to you at the table and beyond.

[To use the “Humble Seat” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

For more table imagery, visit this page.

For more table imagery, visit this page.