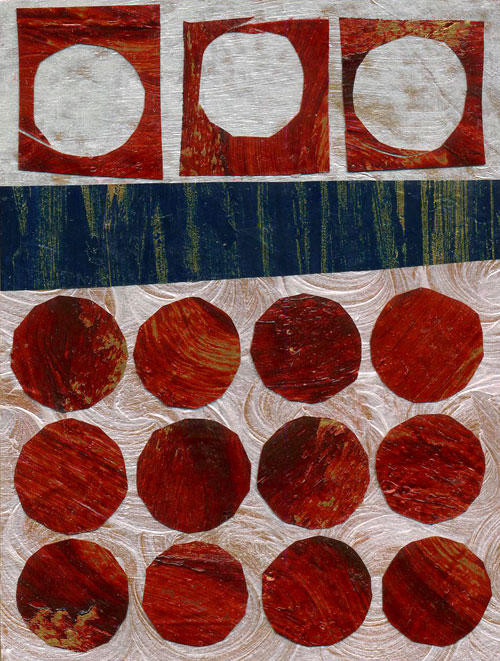

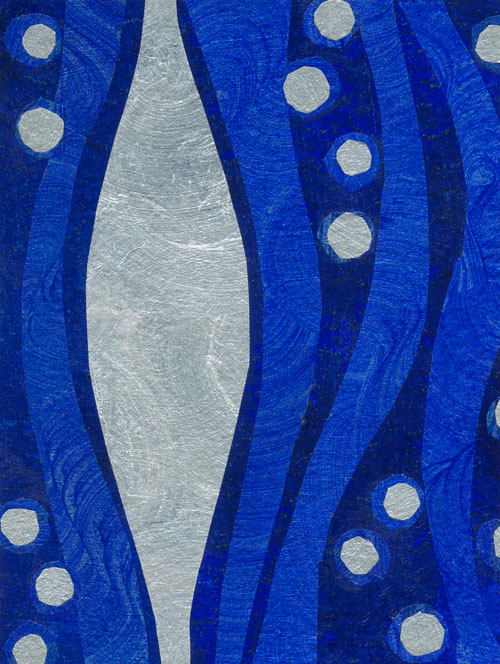

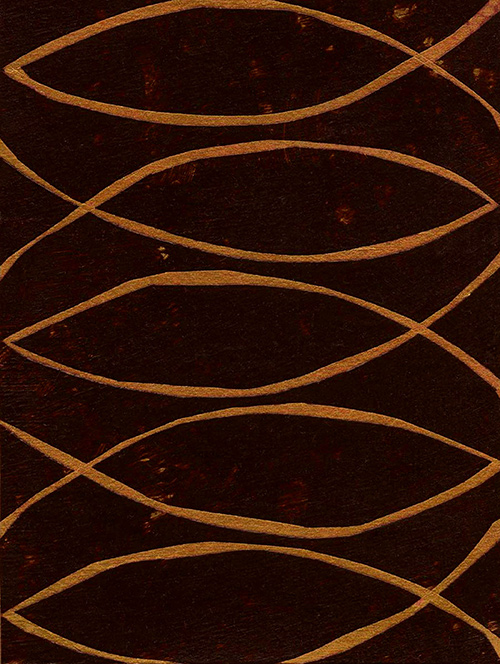

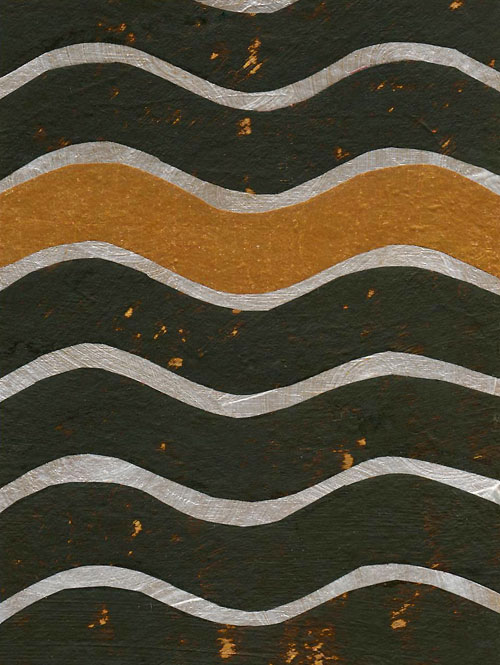

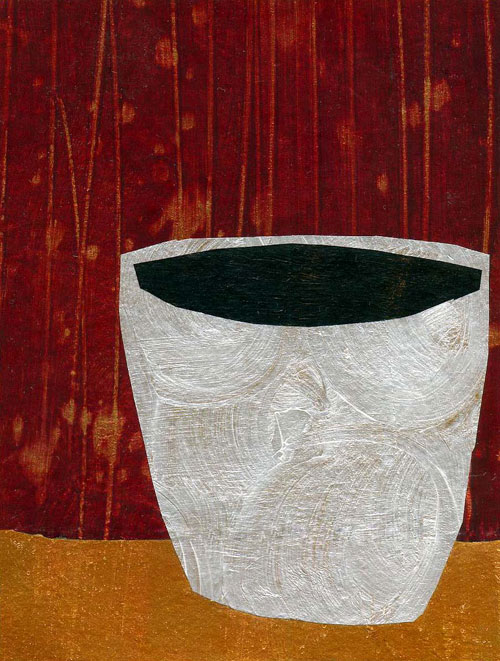

A Thin Place © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 16/Ordinary 21/Pentecost +10: Matthew 16.13-20

When I was in seminary, one of my professors threatened each year to give a Rock of Ages award to the student who made it through their theological education the least changed. We didn’t have such folks in abundance, but they were evident in each class: those who were present solely because their church or denomination required that they have a seminary degree. Sticking it out until they had that parchment in hand, these classmates went through the motions of education but remained impervious to the transformation that it offered.

Though Jesus refers to Peter as a rock in this week’s gospel lection, I suspect that Peter would have eluded such an award as my seminary professor threatened to give. Matthew tells us that Jesus and the disciples visit Caesarea Philippi, where Jesus, after asking his companions who others say that he is, then turns the question on them: “But who do you say I am?” Simon Peter, in a dazzling moment of clarity and insight, tells Jesus, “You are the Messiah, the son of the living God.”

Jesus is elated by Peter’s insight, and he begins to lay a blessing on him. He opens with calling him Simon, harking back to his follower’s former name. Jesus goes on to tell him, “You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it.” Jesus’ naming of Peter plays on the Greek word for rock, petra; his name is sometimes translated as Cephas, from kepha, the Aramaic word for rock.

Peter, however, is a rock of a different sort. Unlike the folks who were candidates for my professor’s Rock of Ages award, Peter is not impervious to change. He exhibits his own points of resistance, to be sure, but he also harbors a fundamental openness to the transformation that Jesus offers. Jesus recognizes that Peter is still in formation. This disciple will yet do things that will provoke Jesus’ ire and disappointment. The human and earthy still run deep in Peter. Yet Jesus glimpses strength within him, and an openness that he knows will become a habitation for the holy.

Pondering this Petrine passage, I find myself thinking of Jacob in the wilderness. Genesis 28 describes how Jacob, having fled for his life, finds himself in a place between the home he has known and the life that is yet ahead of him. As darkness falls in that place, Jacob settles down to rest, laying his head upon a stone. During the night, he dreams of a ladder stretched between earth and heaven, with angels ascending and descending the ladder. He becomes aware of God standing beside him, offering words of promise and sustenance. Waking, Jacob cries, “Surely the Lord is in this place—and I did not know it!” He takes the stone he had used for a pillow, sets it up as a pillar, and pours oil on top of it. Jacob renames the place Bethel: House of God.

Jacob’s stone marks that spot as a thin place, to borrow a notion from Celtic traditions. Celtic folk have long held that in the physical landscape and in the turning of the year, there are places where the veil between worlds becomes thin. It’s not that God is somehow more present in those places, as if God could be more there than elsewhere; rather, something in those places and times invites us to be more present to the God who is always with us. We open, and we see.

Jesus names Peter the rock. In doing so, Jesus signifies that he both recognizes what is within Peter and is also calling forth what has yet to take form in him. In an action that echoes Jacob’s sacramental gesture, Jesus pours a blessing like oil upon Peter. After telling Peter that he will build his church—a house of God—upon him, Jesus goes on to say, “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” His words have the tone of incantation, of ceremony, of one who is initiating another into a sacred role. And, in fact, “binding and loosing” are words that come from the rabbinic tradition; they refer to what happens when a question arises about whether an action may be permitted. Steeped in the law, the rabbis had the power to determine which actions would be forbidden (bound) and which would be allowed (loosed). Jesus confers power upon Peter, an authority so profound that what Peter does will have import in both heaven and earth.

Like Jacob who recognized the presence of God in that in-between place, Peter knows Jesus in an instant of brilliant clarity. Where Jacob turned his stone into a sacrament and renamed that place the House of God, Jesus marks this moment by blessing his disciple and renaming him as a rock who will become a dwelling place for God. Peter himself becomes a thin place; within him meet the things of heaven and the things of earth. What Jacob knew, Jesus knew: this is a place upon which to build something holy.

And so I am asking myself this week, what is solid within me? What do I contain that would serve as the ground for a holy place, a sanctuary? How do I allow sacred ground to inhabit me even as I remain open to transformation, to change, to renovation and renewal? How does this happen for you? What thin place might God be seeking to create in the midst of your life and your own being? What might we need to let go of in order to make room for such a space?

May you recognize the holy in your midst this week, and be a place for it to dwell.

[To use the “A Thin Place” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]