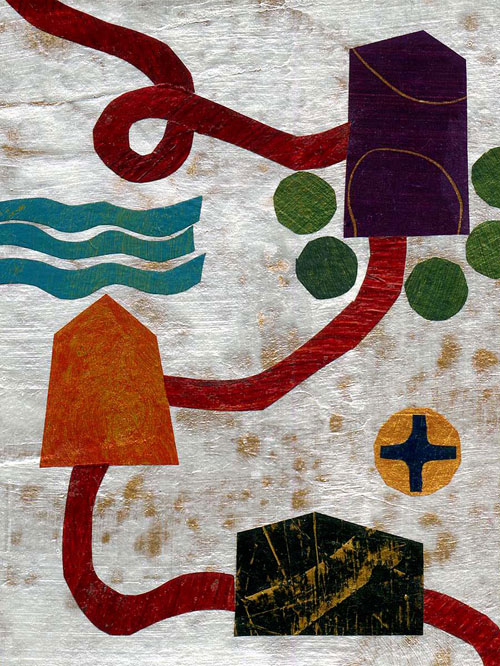

Mapping the Mysteries © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels:

Year A, Proper 6/Ordinary 11/Pentecost +5: Matthew 9.35-10.8 (9-23)

Year B, Proper 9/Ordinary 14/Pentecost +5: Mark 6.1-13

Year C, Proper 9/Ordinary 14/ Pentecost + 7: Luke 10.1-11, 16-20

Early in my ministry, I traveled to Alaska with a mission team from my church. During a free day, we did some exploring that included a stop at the Anchorage Museum of History and Art. As I wandered through the rooms, I found myself in an exhibit titled A World of Maps. These maps were unlike any I had ever seen. Artists from across the United States had taken the familiar forms of cartography, stretching and pushing and translating them into a fascinating library of landscapes. There were altered maps, painted maps, collaged maps. There were maps in the form of sculpture, of books, of pottery. There was a map that unfolded like a scroll, a map in the form of a diptych, a woven map. More than describing the geography of the physical world, these maps charted worlds of imagination, fantastical realms, the terrain of the soul and spirit. The maps told stories of things seen and unseen, and they challenged ideas about borders and boundaries. They embodied the lure and the hazards of exploring worlds unknown—and the worlds we think we know.

This week marks fifteen years that I have been in ministry. Yesterday, as part of my reflecting on this past decade and a half, I pulled out the catalog from that Alaskan exhibit and spent some time revisiting the maps I had encountered so early in my vocation. Looking back, I wonder if part of my fascination with those maps lay in my awareness, even then, of what an uncharted path I was on. I entered ordained ministry with a sense that at some point God would open a door that would take me off the beaten path. I had a gut sense, some hunches, a sense of longing about the ways the path might take shape, but no real idea of how it would unfold.

In this week’s gospel lection, Jesus gives the disciples the closest thing they ever get to a map for their ministry. Telling the twelve to go and proclaim the good news that “The kingdom of heaven has come near,” Jesus provides a rough—not to mention sobering—chart of the landscape they will venture into. He tells them of the hazards the terrain will likely pose, what towns and people to avoid, and how to navigate occasions of hospitality and resistance and hatred. And he gives them the authority to do the work he has called them to do: to chart a path that will be marked by healing and restoration.

So early in their ministries, the disciples could know little of what the territory ahead would actually look like or where it would take them. I wonder—as they looked back after Jesus’ death and resurrection, what kind of map might they have drawn to describe the paths they had walked with him? Reading the landscape with the eye of a cartographer, what marks might they have made to trace their travels? What would those contours and patterns have looked like—the places where, with the authority given to them, they cured the sick, raised the dead, cleansed the lepers, and cast out demons? Or where they shared meals together, or fed those who hungered, or listened to Jesus teach and challenge and encourage and stretch them? Or where they watched him die, and witnessed him alive again? How would they map all the terrain they crossed in the spaces of their own souls?

In Katharine Harmon’s wondrous book You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination, she includes an essay by Stephen S. Hall entitled “I, Mercator.” Hall writes,

I like to say that I never travel without a map, but then none of us do. We all travel with many maps, neatly folded and tucked away in the glove compartment of memory—some of them communal and universal, like our autonomic familiarity with seasonal constellations and the shape of continents, and some as particular as the local roads we have each traipsed. As we navigate on the trip that Dante called “our life’s way,” we are all creating our private maps. Like Mercator, we are not discovering entirely new worlds; rather, we are laying a new set of lines down on a known but changing world, arranging and rearranging metaphysical rhumbs that we associate with successful navigation. To each, her or his private meridians. To each, a unique projection. I, Mercator, and you, too.

This week’s collage is a map I made as I reflected on these past fifteen years in ministry. As with most maps, I can chart the landscape only in retrospect; I recognize the roads because I have traveled them, often making them up as I went along. Making this collaged map, I had certain kinds of landmarks on my mind, but I fashioned it with the awareness that I could have charted the landscape any number of ways. I could have marked the locations where pivotal conversations occurred, where I witnessed healing, where I encountered birth or death. I could have charted the places of peril, of heartbreak, of unexpected wonders. I could have marked the spots where the territory seemed to take me in circles, or was barren, or graced me with splendors. The map might have noted the underground streams, the secret passages, the wellsprings of sustenance, the paths not taken.

And it might tell of those sites where the convoluted terrain finally opened up and spilled me out into a plain where I knew more deeply who I was, what I was called to do, what Christ was giving me authority to do.

Still making the map as I go, I pray for a measure of the imagination of those artists whose work I saw in Anchorage, who pushed and stretched the traditional forms, who ventured beyond the customary boundaries, who dared to look deeper into their landscape, and deeper still. More than that, I pray for the imagination of the one who looked out into the terrain of a world “harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd,” a world broken by illness and injustice, a world bent by pain and hunger. I pray for the imagination of Christ, who dared to look into this world and to ask those who traveled with him, “Want to make a new map?”

So what’s your map look like? How would you chart the terrain of your last fifteen years, fifteen months, fifteen days? What landmarks would you note? What stories would your map tell? What are the maps beneath the map of your life—the hidden landscapes, the secret stories that shape the lay of your land? Are there tools you need in order to do some new mapping—to revisit and rethink and redraw the territory you thought you knew, or to change the course ahead?

Many blessings and traveling mercies as you continue to chart your way.

[To use this artwork, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com.]