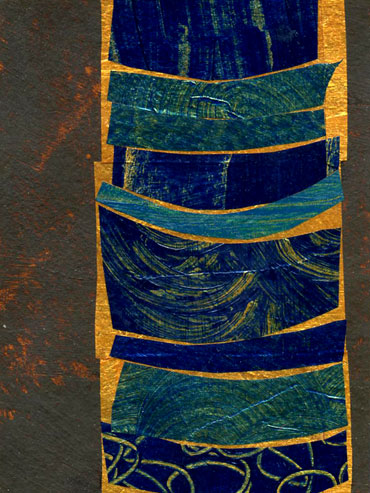

The Way of Water © Jan L. Richardson

If you want to get a feel for how God cares for God’s people, follow the trail of water through the scriptures. Wilderness, exodus, baptism, tempest: whether providing water, saving people from it, immersing them in it, or calming it, God uses water as a vivid sign of providence, deliverance, and grace.

In God’s lexicon of water, wells have a particularly interesting place. Women at wells: more intriguing still. See a woman near a well, something momentous is bound to happen. It often involves a person of the male persuasion, and it augurs a major change in the woman’s life. Genesis gives us a rich quartet of woman-at-the-well stories. The book offers two accounts in which Hagar meets God—or an angel of God—at a well in the wilderness: the first time, in Genesis 16, Hagar has run away, fleeing from the harshness of Sarai. The second time, in Genesis 21, God provides a well to a desperate Hagar and her son Ishmael, who lies near death in a waterless wilderness. Genesis 24 tells of a servant who finds Rebekah, Isaac’s bride-to-be, at a well. Another well serves as a signal of matrimony in Genesis 29, when Jacob meets Rachel at the well where she waters her father’s sheep.

The matrimonial symbolism of wells finds a striking resonance in the Song of Songs, where the bridegroom extols the virtues of the bride’s…um…well, channel is how the NRSV translates it; “a garden fountain, a well of living water, and flowing streams from Lebanon,” the bridegroom gushes (Song 4.15).

Particularly given the intimate, fertile link between women, wells, marriage, and motherhood, one might rightly wonder what the heck Jesus is doing, hanging out by a well with a lone woman, as he does in this week’s Gospel lection, John 4.5-42. It’s a curious thing for a single rabbi to strike up a conversation with a woman he finds at a well. But Jesus is a curious sort of rabbi, and so he wades into an exchange with a Samaritan woman who has come to draw her water at noonday.

Their talk of literal water turns toward a conversation about the living water that Jesus offers. The woman is thirsty, and she asks Jesus for this living water. Perhaps wanting to allay any potential misunderstanding about what he is offering (after all, this woman probably knows the stories about what happens to women and men at wells), Jesus tells her to go and bring her husband. No husband; she’s had five of those, as Jesus well knows; he knows, too, that she is not married to the man she is living with now. Contrary to some interpretations, there is no note of judgment here. Any number of explanations could account for marital multiplicity in a woman of that culture. Whatever her circumstances may be, Jesus’ words here do not signify condemnation; they are a statement of fact that conveys his remarkable insight, his deep knowing of this woman and her life.

The woman recognizes Jesus’ insight as the mark of a prophet, and this prompts her to turn the conversation toward a liturgical matter. She touches on the source of division between the Jewish and Samaritan people: their difference of belief in the location of the proper place to worship God. The Samaritans held that “this mountain,” Mount Gerizim, was the correct place of worship, while the Jews maintained that Jerusalem was the rightful place. There by the well, Jesus assures the woman that a time is coming when such questions will fall away, and all who worship God will worship “in spirit and truth.” Their theological exchange culminates with Jesus’ telling the woman that he is the Messiah of whom she has spoken.

At this point the disciples turn up, astonished that Jesus is talking with this woman (perhaps they, too, know the stories of men and women at wells). Neither Jesus nor the woman is fazed. Here John provides a detail that’s the clincher for me. “Then the woman,” he writes, “left her water jar and went back to the city.”

She left her jar. She left her jar behind, that water-bearing vessel on which she depended for her very life. She abandoned it at the well.

She had become the vessel. Filled with the living water that she found in the midst of her mundane, daily task, the woman goes to spill forth what she has found.

Early in their conversation, this Samaritan woman had made a point of making sure that Jesus knew that this well belonged to her ancestor Jacob. Jacob, who wrestled with God by a river and received a new name. At Jacob’s well, his womanly descendant does her own wrestling with God. She is unnamed, all throughout John’s story, but not unchanged.

The woman departs the well with no husband, no son, no earthly male to hitch her star to. She leaves not with a man but with a message: Come and see. This unmarried, unnamed woman of Samaria becomes an evangelist, a disciple, a witness to the Messiah. She is a vessel of living, liberating, life-giving water.

Where have you heard life-giving words that helped you feel known? What word of good news might God be calling you to embody and to pour forth in this season? Is there a vessel that you need to leave behind in order to follow the way of Christ?

May you find—and offer—a wellspring this day.

[To use this image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com.]