Getting Garbed © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 23/Ordinary 28/Pentecost +17: Matthew 22.1-14

I have anxiety dreams. Not frequently, mind, but they do pop up once in a while. And for the past couple of years it’s been the case that when the anxieties floating around my subconscious emerge in a dreamscape, they tend to attach themselves to one activity in particular:

Weddings.

I have anxiety dreams about other people’s weddings. I’m performing the ceremony, and I’m running late. Or I’m in the church, but I can’t get to the sanctuary. Or the ceremony is about to happen, and I realize we haven’t actually planned it. Or I don’t have my robe.

I have anxiety dreams about my own wedding, which, God willing, will take place about this time next year. (Note to those who know us: this does not constitute an announcement! It’s not official; we haven’t set the actual date!) It’s the day of the wedding, and I haven’t sent out the invitations. Or we’ve taken care of every detail except for actually planning the service. Or the wedding starts in five minutes and I haven’t dressed. Or I don’t have a wedding gown.

The anxious landscape of those wedding dreams feels to me a lot like the setting of this Sunday’s gospel lection. In Matthew 22.1-14, we find a wedding banquet that is, by turns, wondrous and terrible. It reminds me, in fact, of the old “That’s good! That’s bad!” shtick. In this case, it would go something like this:

A wedding banquet! That’s good!

No, that’s bad; the invited guests didn’t come!

But the king sent people to look for them! That’s good!

No, that’s bad; they killed them and burned their city!

But then they went into the streets and invited everyone they found! That’s good!

But then the king saw a guy who wasn’t wearing a wedding robe, and he had his attendants throw him into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth!

Oh, that’s bad. Definitely very bad.

It’s a wondrous text. In its high points, it shares similarities with Luke 14.15-24; both passages contain parables of a great wedding banquet to which the invited guests find reasons not to go, and so a wild and wondrous array of last-minute B-list folks wind up enjoying a splendid feast. It’s one of my favorite depictions of the kingdom of God.

It’s a terrible text. In his version of the wedding banquet, Matthew sets the stakes considerably and painfully higher than does Luke. Those who refuse to come suffer violent repercussions. Matthew’s inclusion—and punishment—of the hapless, robeless fellow strikes a particularly curious note that feels like a scene out of one of my wedding anxiety dreams.

The fellow comes to the banquet, after all, but somehow, whether by intention or inadvertence—the text isn’t clear—he misses the line where they were handing out wedding robes. The severe punishment inflicted upon him got me wondering about the significance of the missing wedding garment, and, beyond that, about the symbolism of clothing in scripture, and how it bears on this story.

Given that the Bible doesn’t always provide a wealth of descriptive details, I was surprised and then fascinated as I considered the scriptures with garments in mind. Significant mention is made of clothing from almost the very beginning. When God exiles Adam and Eve from Eden, God does not leave them to their fig leaves; in a charmingly domestic gesture, God “made garments of skins for the man and for his wife, and clothed them” (Gen. 3.21). Exodus tells of the lavish vestments fashioned for Aaron and his sons, clothing that was intertwined with their ordination and service as priests of God. When Ruth, a stranger from another land, seeks security in her new home, she goes by night to her kinsman Boaz, asking of him, “Spread your cloak over your servant” (Ruth 3.9). In Matthew’s gospel, the hem of Jesus’ robe becomes a conduit of healing for a woman who has bled for years (Mt. 9). The father of the prodigal son cries out for his returning child to be garbed in the best robe (Luke 15.22). In John’s version of the crucifixion, the soldiers’ division of Jesus’ clothing and their casting of lots for his tunic is seen as a fulfillment of Psalm 22: “They divided my clothes among themselves, and for my clothing they cast lots” (John 19.24).

The book of Revelation surpasses all others in taking particular note of what people are wearing; their garb is laden with symbolic import, with white robes achieving particular prominence. The visionary John draws our attention to “one like the Son of Man” who is clothed with a long robe and a golden sash (Rev. 1), white robes that will be given to members of the church in Sardis “if you conquer” (Rev. 3), the twenty-four elders surrounding the throne who wear white robes and golden crowns (Rev. 4), martyrs who receive a white robe (Rev. 6), a multitude clad in robes that have been made white by washing them in the blood of the Lamb (Rev. 7), an angel garbed with a cloud (Rev. 10), witnesses who prophesy wearing sackcloth (Rev. 11), a woman clothed with the sun (Rev. 12), seven angels robed in pure, bright linen and golden sashes (Rev. 15), a bride clothed with fine linen that is the righteous deeds of the saints (Rev. 19), and a rider wearing a robe dipped in blood who is followed by armies clad in fine white linen (Rev. 19).

Clothing carries such symbolic weight that, in the scriptures, simply being in relationship with God and doing what God would have us do is spoken of in the vocabulary of textiles. “I put on righteousness,” Job claims in one of his discourses, “and it clothed me; my justice was like a robe and a turban” (Job 29). “I will greatly rejoice in the Lord,” Isaiah exults, “…for he has clothed me with the garments of salvation, he has covered me with the robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom decks himself with a garland, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels” (Isaiah 61).

From Genesis to Revelation, clothing takes on significance in virtually every case as a sign of God’s providence. Time and again, God cares for God’s people by providing clothing for them. It is a tactile, tangible, textured sign of God’s mercy, care, and love. Perhaps to help make up for giving us such vulnerable skin, God works to ensure that we have something to wear. So important is this that God compels us to participate with God in providing clothing for one another. Covering the naked with a garment is among the list of actions in Ezekiel 18 that make a person righteous. Jesus picks up this theme with particular directness in Matthew 25: “Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world…I was naked and you gave me clothing….” And if anyone takes our coat, Jesus tells us, “do not withhold even your shirt” (Luke 6).

So providential is God on this point that Jesus specifically instructs us not to sweat the clothing issue. “And why do you worry about clothing?” he asks. “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field,” Jesus continues, “which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith? Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What will we eat?’ or ‘What will we drink?’ or ‘What will we wear?’” (Matthew 6.28-31).

So, given how hospitable God is when it comes to garbing us, what’s the deal with the garmentless guy getting booted out into the teeth-gnashing darkness? Where is the good news in this parable?

I’m intrigued by the suggestion, posed by a couple of folks I’ve come across, that we rethink our tendency to assume that the king of this parable is God, who comes off looking supremely grumpy and vindictive in this tale. These exegetes suggest that the king instead symbolizes earthly authorities, and the robeless man thrown into the darkness in fact refers to Jesus. They draw our attention in particular to Isaiah 52.13-53.12, where the prophet describes the suffering servant. In his silence and in his afflictions, the servant indeed bears a resemblance to the wedding guest whom the king commands his attendants to bind and throw into the darkness.

Particularly bearing in mind that Jesus grounded his teachings in the Hebrew Scriptures, it’s an enticing suggestion to ponder. I’m not clear, however, that it explains everything. Jesus is telling the parable to describe the kingdom of heaven, and it seems hard to get around the implication that the king in this kingdom is, well, God.

The text doesn’t provide enough clues for us to be certain whether the wedding guest was missing a robe by intention or by accident. Jesus seems to imply that the guest failed to properly receive the sacred hospitality extended to him, or to receive it fully enough—he deigned to come to the feast, but not to wear the correct attire—and therefore was punished in such a fashion that one wonders if perhaps it would have been best for him not to have come at all.

Given the scriptural witness to God’s bias in favor of garbing the garmentless, it seems fair to interrogate the text and its traditional interpretation. At the very least, we need to read Jesus’ parable in light of the scriptures’ well-established depiction of God as one whose propensity for clothing us extends even to the prodigal.

For my part, in pondering this passage in the realm of lectio divina, all my wonderings have come down to this:

What am I clothing myself in? Or, perhaps more precisely, how am I allowing God to garb me these days?

Am I feeling good because I’ve accepted God’s invitation to show up at the feast, but in truth have neglected to open my arms fully to the wonders before me? Am I harboring some sense of rebelliousness—I’ll come in for the party, but you can’t make me dress right? Given that I think a measure of well-placed rebellion is okay, how do I work to ensure that I’m not directing my rebelliousness toward God and God’s hospitable intentions toward me? And on those occasions when I’m wrestling with God, or needing things to be less intense in my relationship with God, or when I simply need to temporarily set aside a metaphorical holy cloak that’s grown too weighty or wearisome, can I trust that God won’t bind me and send me into the darkness to gnash my teeth? If, in my waking life, I’ve wandered into a landscape that feels like those wedding anxiety dreams—I’m not in the right place, I can’t get there, I’m not ready, I don’t have the right thing to wear—can I rest in the God who gives party clothes to the prodigal and spreads a cloak over the stranger and, in baptism, clothes us with Christ’s own self (Galatians 3)? Can I trust that this same God will provide what I need and will let me linger at the feast?

I think I can do that. How about you?

In her wondrous book Showings, also known as Revelations of Divine Love, the medieval English mystic Julian of Norwich wrote, “Our good Lord is our clothing that, for love, wraps us up and winds us about, embracing us, all beclosing us and hanging about us, for tender love.” In these days, may you know the beclosing clothing of Christ, and extend it to those who cross your path. Blessings.

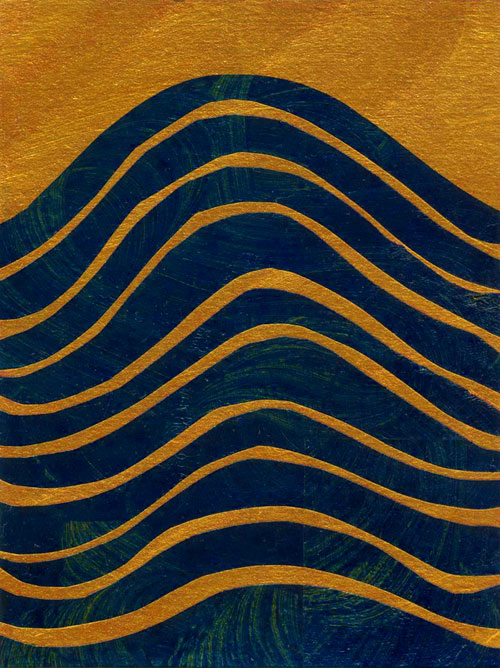

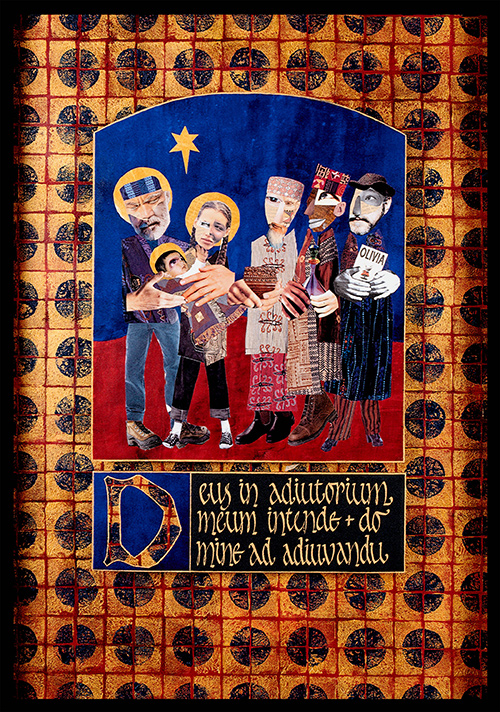

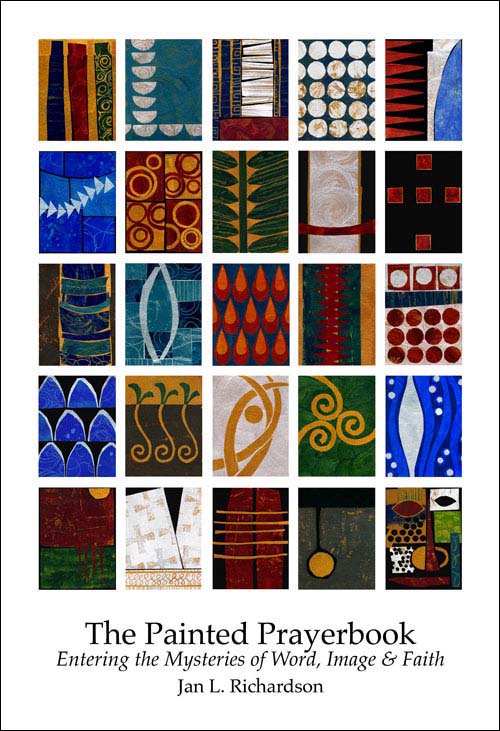

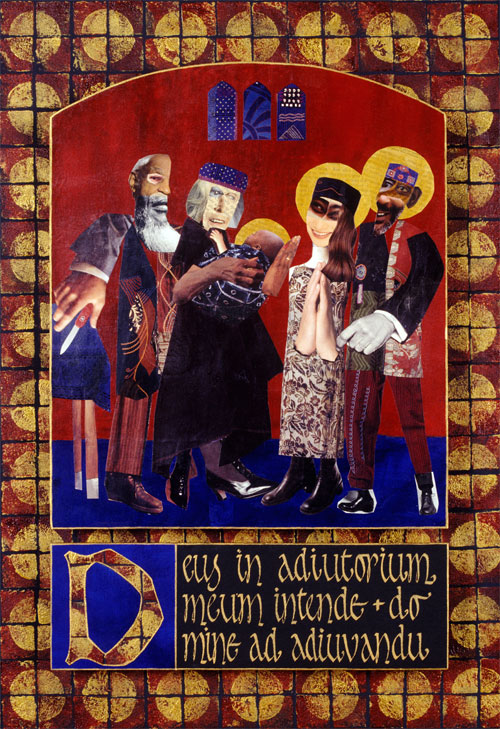

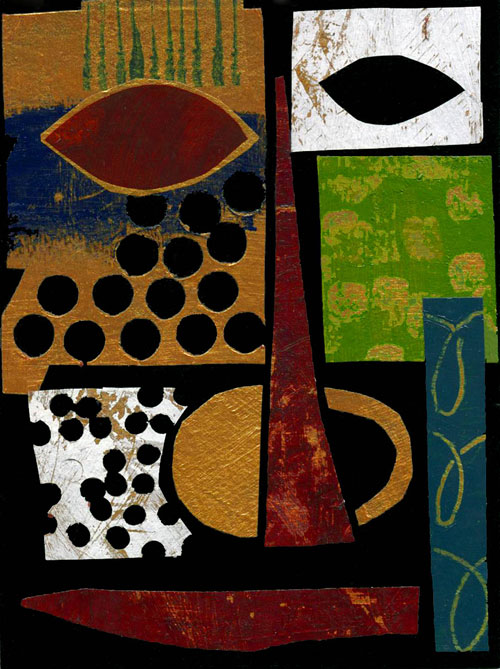

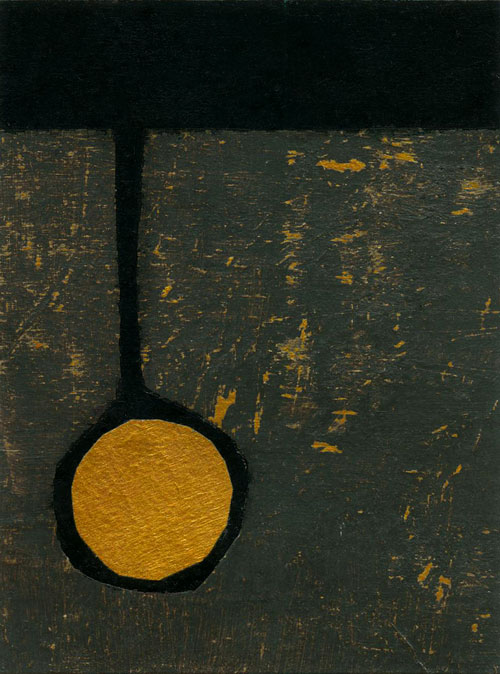

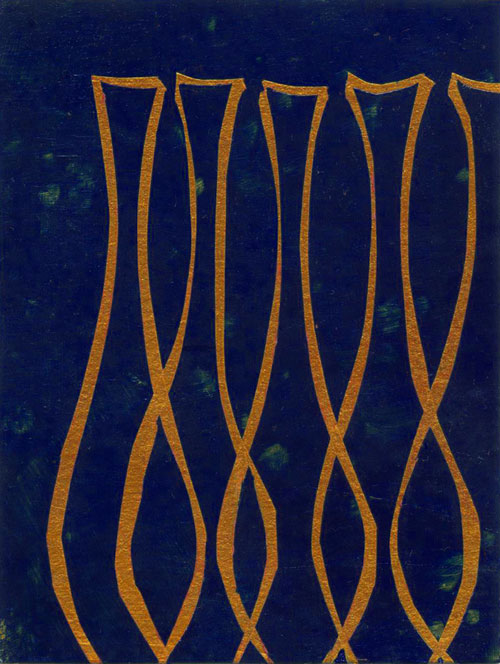

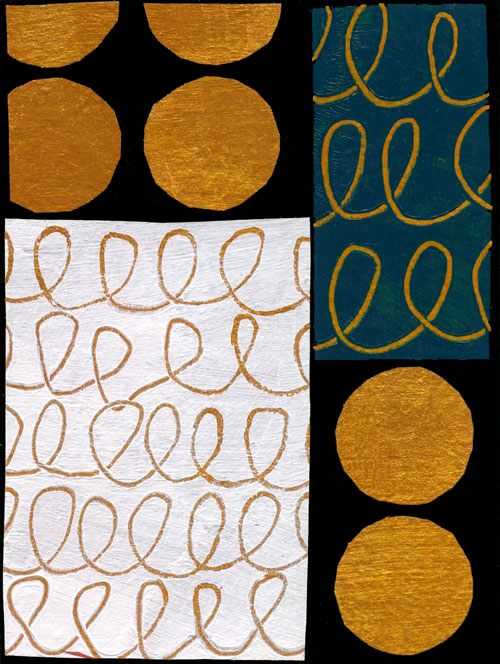

[To use the “Getting Garbed” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

[Julian of Norwich quotation cited by Gail Ramshaw in Treasures Old and New: Images in the Lectionary.]