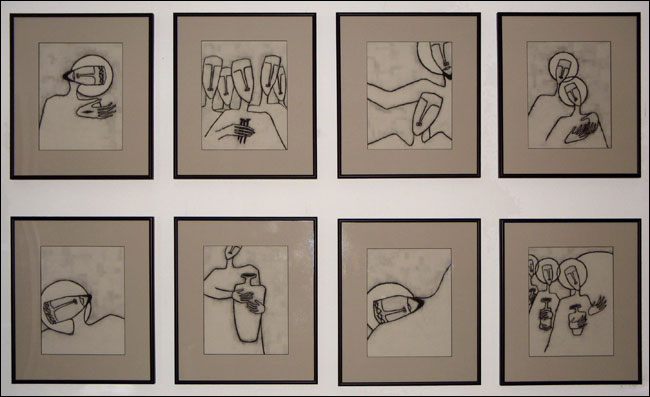

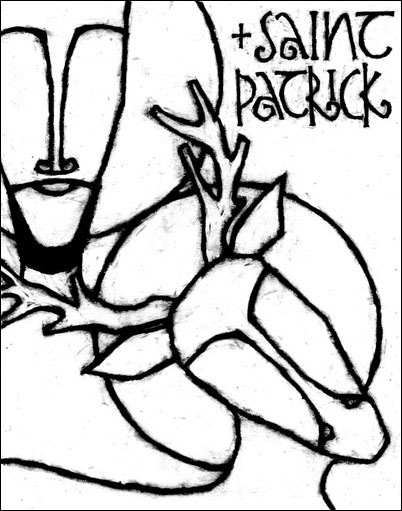

Image: Ash Wednesday © Jan Richardson

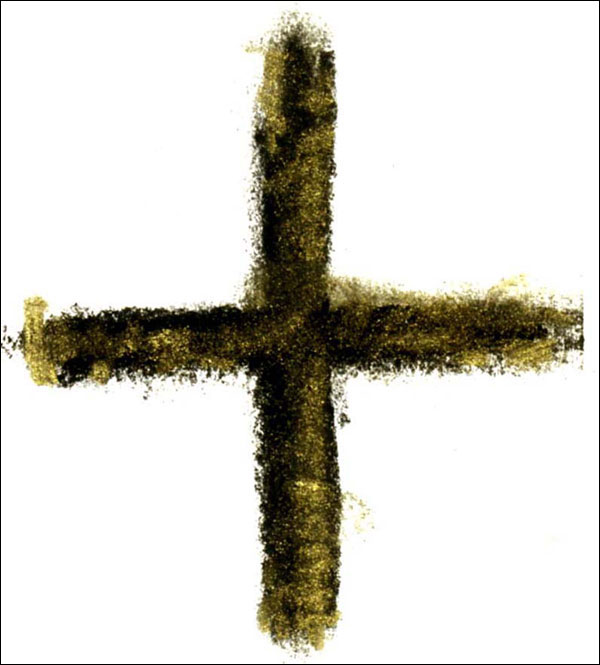

Image: Ash Wednesday © Jan Richardson

Readings for Ash Wednesday: Joel 2:1-2, 12-17; Psalm 51:1-17;

2 Corinthians 5:20b – 6:10; Matthew 6:1-6, 16-21

When I received the invitation to do the artwork for Peter Storey’s book Listening at Golgotha, a series of reflections on the Seven Last Words of Jesus (featured in Friday’s post), it came as a lovely bit of synchronicity. His editor, who had been the editor for my first book, wasn’t aware that Peter and I were acquainted, having crossed paths on a few occasions when he was visiting the U.S. from his native South Africa. The catch was that the artwork had to be in black and white. With my having worked primarily in paper collage, black and white was not exactly my first language, artistically speaking. I so wanted to work on Peter’s book that I told the editor yes. Then I set about to figure out what kind of black and white medium I could manage.

I tried doing collages in black and white, but made little headway. After several other experiments, I picked up a piece of charcoal. And fell in love.

Beginning to work with charcoal was like learning a new language, with the delights and challenges that come in such a process of discovery. Most of my early sketches were a mess. I could sense that a style was stirring, but in the beginning stages it appeared so raw and unformed that I began to despair of having anything ready in time for Peter’s book.

On the verge of calling the editor to do an embarrassing backing-out dance (an awkward jig that I try hard to avoid), I instead called my artist friend Peg to ask if she could either collaborate with me or counsel me on the project. Peg told me to bring her all the sketches I’d done: the good, the bad, and the ugly. To my eye they were mostly bad and ugly. But Peg took the smudgy, ashy papers, spread them out, and pondered them. In a fashion that struck me as being something like lectio divina, she followed their tangled lines until she began to perceive something that had the beginnings of coherence and form. Moving through what I had perceived as chaos, Peg showed me what she saw, and she offered suggestions on how to pursue and develop the path that had been obscure to me. Not only did this help make it possible to complete the project, but it also began to open creative doors within and beyond me in ways I never would have imagined.

In large part, what I came to love about working in charcoal was the dramatic contrast it offered to my colorful, often intricate collage work. Where collage involves a process of accumulation and addition as the papers are layered together, charcoal invites me to an opposite experience. When I do a charcoal drawing, my goal is to find the fewest number of lines necessary to convey the scene. It is a medium of subtraction, involving little more than a piece of blank paper, a stick of charcoal, and an eraser to smudge and then smooth away all that is extraneous. What remains on the page—the dark, ashen lines—is spare, stark, sufficient.

For every artist, one of the most crucial habits to develop is staying open to what shows up. In the process of cultivating a unique vision, with all the consuming focus that involves, we have to learn, at the same time, how to keep an eye open for the creative surprises and invitations that can lead us to new pathways or deepen existing ones. If I stay too attached to a favorite medium or familiar technique, I risk shutting myself off to possibilities that can take me to whole new places in my work and in my own soul.

Taking up a new medium, entering a different way of working, diving or tiptoeing into a new approach: all this can be complex, unsettling, disorienting, discombobulating. Launching into the unknown and untried confronts us with what is undeveloped within us. It compels us to see where we are not adept, where we lack skill, where we possess little gracefulness. Yet what may seem like inadequacy—as I felt in my early attempts with charcoal—becomes fantastic fodder for the creative process, and for life. Allowing ourselves to be present to the messiness provides an amazing way to sort through what is essential and to clear a path through the chaos. To borrow the words of the writer of the Psalm 51, the psalm for Ash Wednesday, it creates a clean heart within us.

Ash Wednesday beckons us to cross over the threshold into a season that’s all about working through the chaos to discover what is essential. The ashes that lead us into this season remind us where we have come from. They beckon us to consider what is most basic to us, what is elemental, what survives after all that is extraneous is burned away. With its images of ashes and wilderness, Lent challenges us to reflect on what we have filled our lives with, and to see if there are habits, practices, possessions, and ways of being that have accumulated, encroached, invaded, accreted, layer upon layer, becoming a pattern of chaos that threatens to insulate us and dull us to the presence of God.

Each of the scripture texts for this day invites us to ponder the practices that we have given ourselves to, and the practices to which God calls us, both individually and in community. The prophet, the psalmist, the apostle, and Jesus himself all urge us, in these readings, to pay attention to the rhythms of our lives so that we may discern which rhythms draw us closer to God and which ones pull us away.

Where do these sacred texts find you as we cross into the season of Lent? What is the state of your heart? What has taken up residence there over the past weeks, months, years? Are there habits and ways of being that you are so invested in, so attached to, that it has become difficult to discern new directions in which God might be inviting you to move? Who can help you ponder the patterns present in your life—the good, the bad, the ugly—and help you see where new life is stirring, and where a new path might be opening? What are the most basic, elemental, crucial things in your life, and how might God be challenging you to give your attention to them in this season?

The gospel for Ash Wednesday tells us that where our treasure is, there our hearts will be also. On this day, and throughout the coming days, may we see clearly where our treasure lies, and have hearts clear and open enough to recognize the surprising forms that such treasure can take. On this day of ashes, blessings to you.

[For last year’s reflection on Ash Wednesday, visit Ash Wednesday, Almost.]

[To use the “Ash Wednesday” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of the Jan Richardson Images site helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]