Getting Grounded © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Proper 10/Ordinary 15/Pentecost +4 (July 10): Matthew 13.1-9, 18-23

During our recent Saint Brigid’s retreat, we were treated to a poetry reading from Father Kilian McDonnell, one of the Benedictine monks of Saint John’s Abbey, where our retreat took place. Having been on the retreat a few years earlier when Fr. Kilian came and shared his poems, I had been looking forward to his return visit with much anticipation.

For most of his life Fr. Kilian (who I first introduced in this post at The Advent Door) has worked as a theologian—teaching at Saint John’s University, writing scholarly books and articles on systematic theology, and taking a leading role in ecumenical work. At 75, in his so-called retirement, Fr. Kilian began to write poetry. In an essay that he wrote eight years after his poetic beginnings and included in his first published collection of poems (Swift, Lord, You Are Not), Fr. Kilian describes how, while reading a poem in the New Republic, “I said to myself, ‘I think I can do as well.'”

He acknowledges that his career as a scholar writing theology “out of a dogmatic, abstract, highly authoritarian, text-bound tradition” and dealing not only with the scriptures but also with “conciliar decrees, papal encyclicals, episcopal pronouncements, all highly conceptual, content and meaning-oriented,” had not prepared him particularly well for a vocation as a creative writer. “Too much imagination in theological writing,” Fr. Kilian observes, “can bring you to the stake.” Even in his own monastery, Fr. Kilian’s turn toward poetry was looked on by some as, if not outright dangerous, then a frivolous pursuit; he tells in one of his poems of a monk in the community who says, “Kilian does not have/enough to do./He writes poetry.”

Yet he has persisted. And as he prepares to turn 90 this year, Fr. Kilian is anticipating the publication of his fourth book of poems (the first having been followed by Yahweh’s Other Shoe and God Drops and Loses Things). It’s due out next month and is titled Wrestling with God. During his afternoon with us, Fr. Kilian gave us a sneak peek of the poems in this forthcoming book.

Most of Fr. Kilian’s poetry finds its grounding in the scriptures. And while some folks with stereotypes about monks, poetry, and the scriptures—let alone a combination of the three—might suppose that a longtime monk who takes his inspiration from the Bible would produce poetry that is ethereal or sentimental, Fr. Kilian’s poems provide a wondrous witness to how the contemplative life calls us deeper into the world, not away from it. Part of Fr. Kilian’s charm and punch as a poet lies in his earthiness (evident in such poems as “The Ox’s Broad Behind”), as well as in his willingness to go deep and deep into the layers of the biblical stories and to confront and call forth, with his piercing poet’s eye, the complexities of human life in this world given to us by a God who is both marvelous and maddening.

I will tell you that it is a wonder to be in the poetic presence of someone who has been pondering the Word—praying with it, contemplating it, ruminating upon it—in spitting distance of a century. Although we are not all called to become poets, Fr. Kilian’s deep engagement with the Word offers a window onto a life where the Word has found good soil and has born fruit, as this week’s Parable of the Sower calls us to.

As I ruminate on this week’s parable, I find myself wondering: What soil—what earth—is the Word finding in our own lives these days? How do we seek out the Word—in the scriptures and in the person of Christ—in the rhythm of our days? How willing are we to go deep into the layers and complexities it offers to us? How do we take the Word into ourselves and let it take root across the span of seasons and years? What fruit are we called to let the Word bear in and through us?

A Blessing with Roots

Tug at this blessing

and you will find

it is a thing

with roots.

This is a blessing

that has gone deep

into good soil,

into the sacred dark,

into the luminous hidden.

It has been months

since the ground

gathered the seed

of this blessing

into itself,

years since the earth

enfolded it.

Sometimes

that’s how long

a blessing takes.

And the fact

that this blessing

should finally show

its first fruits

on the day

you happened by—

well, perhaps we shall

simply call the timing

of this ripening

a mystery

and a sweet grace.

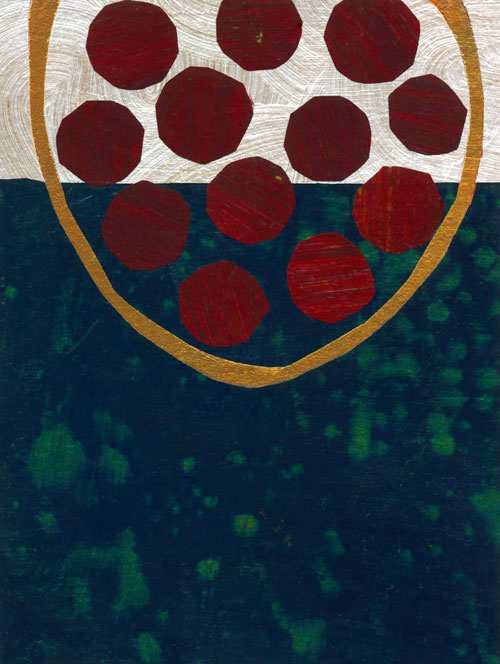

Take all you want

of this blessing.

Take every morsel

that you need for

the path ahead.

Let its fruits fall

into your hands;

gather them into

the basket of

your arms.

Let this blessing

be one place

where you are willing

to receive

in unmeasured portions,

to lay aside

for a moment

the way you ration

your delights.

Let yourself accept

its inexplicable plenitude;

allow it to give itself

to sustain you

not simply for yourself—

though on this bright day

I might be persuaded

to think that would

be enough—

but that you may

gather its seeds

into yourself

like the ground

where this blessing began

and wait

with the patience

of seasons

and of years

to bear forth

in the fullness of time

a stunning harvest,

a plenteous feast.

P.S. For a previous reflection on this passage, see Getting Grounded.

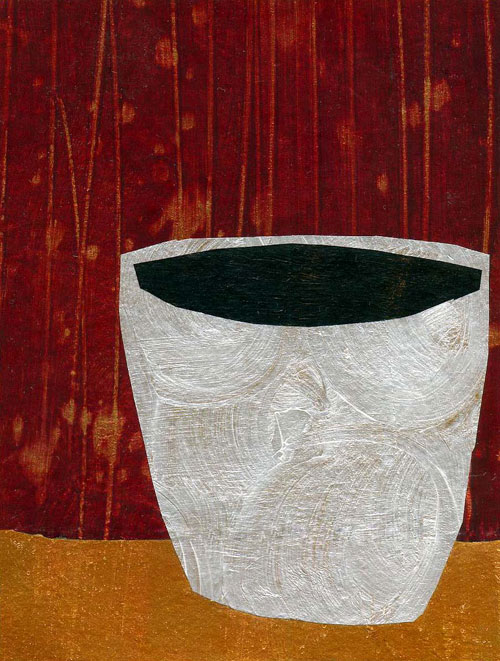

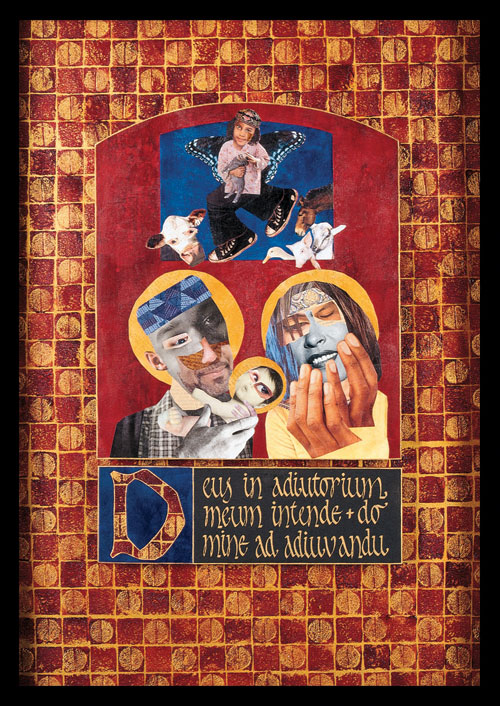

[To use the “Getting Grounded” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

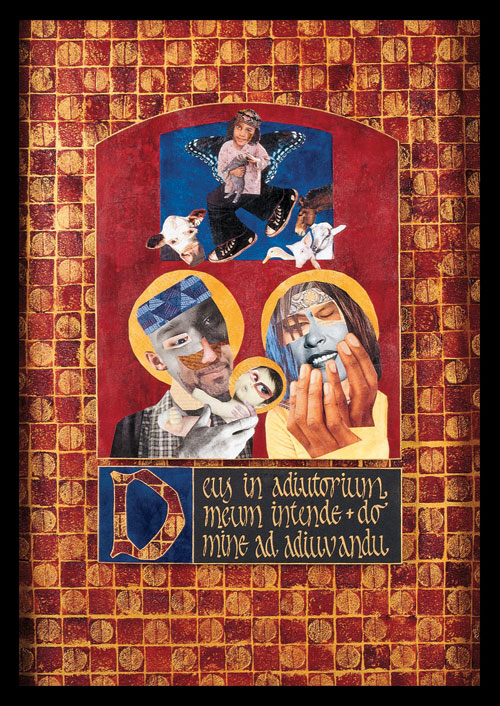

Related artwork: