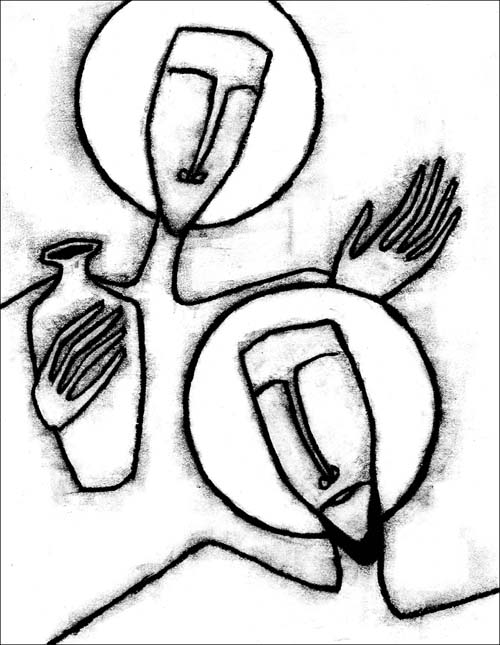

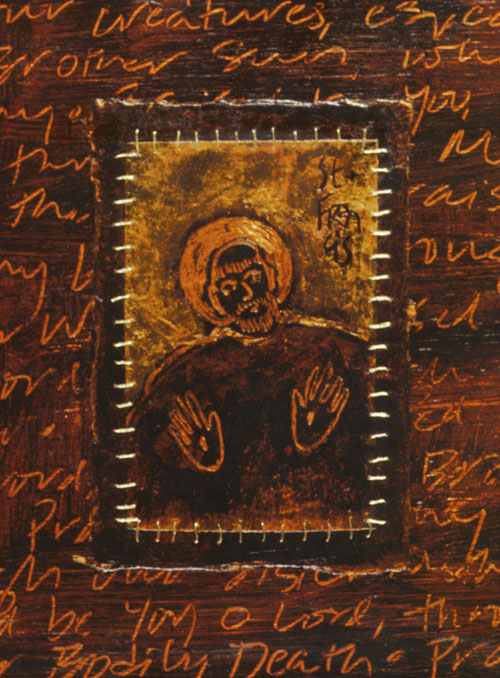

The Domestic God © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 5, Year B: Mark 1.29-39

So we had a lovely little celebration on Saint Brigid’s feast day last Sunday. I invited my sweetheart Gary and our friend Linda over for tea that afternoon. Like me, Linda is an oblate of Saint Brigid of Kildare Monastery. We three had time for a cup of jasmine tea, a slice of cappuccino cheesecake (Brigid would’ve loved cheesecake if she’d known of it), and a few strawberries before the next phase of our celebration: a conference call with a bunch of other folks from the Saint Brigid’s community. Scattered across a physical distance that stretches from California to the Dominican Republic, we joined together for a feast day liturgy that brought us close across the miles.

Then Linda and Gary and I had more cheesecake.

I don’t do a huge amount of entertaining. This owes to a combination of factors including my need for copious amounts of solitude (especially with a book deadline coming up this summer) and the fact of my wee living space, which tends to discourage the gathering of more than, say, a half dozen folks at once (and that’s if some of them sit on my futon). My cozy studio apartment has an efficiency kitchen that Gary calls my yoga kitchen, as getting something out of the tiny refrigerator that sits under the sink sometimes involves doing contortions. Since I’m not wildly domestic, my two-burners-and-a-toaster-oven arrangement suits me okay, most days.

Still, when I get my act together to invite even a friend or two over for a cup of tea or a meal, I love sharing my home and receiving the gift of a loved one’s presence in my quiet space. At times such an occasion feels like a miracle. In the cup, in the conversation: sustenance and grace.

I sometimes tend to overlook the ordinary miracles that unfold in the domestic realm. So often do I take it for granted that on a daily basis, several times a day, there will be something to fill my hunger, and that I will be able to reach for it. But this week, with Saint Brigid’s festive tea lingering with me (along with the stories of the domestic provisioning for which she was especially known, including wondrous feats involving bacon and butter and beer) and with this Sunday’s gospel lection on my mind, I’m paying particular attention to what’s going on the everyday sphere of home, looking to see where the mundane gives way to the miraculous.

This Sunday’s gospel leads us straight into a home, that of Simon (Peter) and Andrew (Matthew and Luke refer to it solely as Simon/Peter’s house). Jesus has come straight from the synagogue, where he cast out the unclean spirit of last week’s reading. Once inside the house, he learns that Simon’s mother-in-law is in bed with a fever. He goes to her, takes her by the hand, lifts her up. In his gesture of reaching toward the woman, touching her, Jesus crosses with great intention into her condition, her realm, her world.

Here we see the domestic Jesus, the intimate Jesus. Crossing from the house of worship into the home of Simon, standing at the bed of a woman whose body has been disordered by illness, Jesus conveys with his outstretched hand that there is no sphere that he does not control, no suffering that is beneath him to heal, no place where he does not desire wholeness and peace. He makes clear that his power is present in every realm, the home no less than the synagogue. He extends his healing to all, the woman in the grip of a fever no less than the man in the clutch of an unclean spirit.

There is no place, no person, unworthy of a miracle.

In response to her healing, Simon’s mother-in-law begins to serve Jesus and his companions. Where other stories of healing sometimes end with the recipient offering a verbal testimony to what Jesus has done (as we will see in next week’s gospel), this story does not ascribe any words to the woman. Whatever she may have said, if anything, the act of her serving Jesus and his companions, her ministering to them in this basic, bodily way, provides eloquent testimony in the vocabulary that she has at hand. That her act falls squarely in the realm of what society sometimes, wrongfully, denigrates as “women’s work” does not minimize its grace. Rather, it unveils the holiness present—and sometimes hidden—in the everydayness of domestic life.

In her commentary on this passage in The Women’s Bible Commentary (Carol Newsom and Sharon Ringe, eds.), Mary Ann Tolbert points out that the word denoting the woman’s action, rendered in the NRSV as serve (from the Greek root diakoneo, related to the word for deacon), is the same word used to describe what angels do for Jesus at the end of his forty days in the wilderness. The choices of some translators, however, have elevated the service of the angels over that of the woman; for instance, translating the action of the angels as “ministering” to Jesus—a more overtly sacramental act—and the woman’s action as “serving” him, which gives a subservient cast to her gift. “The author of Mark,” Tolbert observes, “by using the same word for the action of the angels and the action of the healed woman, obviously equated their level of service to Jesus. What the angels were able to do for Jesus in the wilderness, the woman whose fever has fled now does for him in her home.” Tolbert goes on to note that the door of the woman’s house “becomes the threshold for healing for all in the city who are sick.”

What Jesus later says of a woman who blesses his body with an anointing, we can say of this woman who blesses his body with her domestic gesture: she has done what lay in her power (Mark 14.8, New English Bible). Can the same be said of us? In the places in which our lives unfold, what lies in our power to do? What ordinary miracles hide out in the rhythm of our days, beckoning us to see them or to help enact them? What miracles might Christ be inviting our participation in, as a response and witness to his presence? What’s going on in your home, and how might Christ be wanting to show up within it?

Wherever you live, may Christ bless you there.

With Linda on Saint Brigid’s Day

[To use the “Domestic God” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]