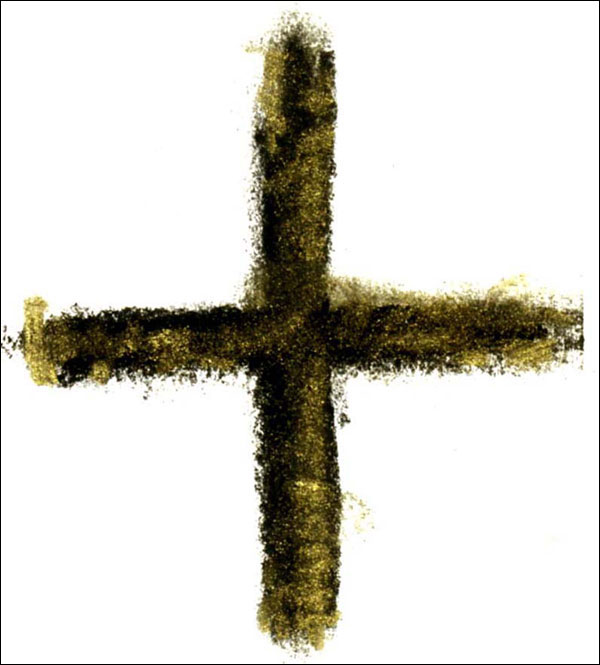

Image: To Have without Holding © Jan Richardson

Image: To Have without Holding © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 17/Ordinary 22/Pentecost +11: Matthew 16.21-28

One summer when I was preparing to become a minister, I spent the season doing a unit of Clinical Pastoral Education at a hospital in north Florida. CPE is something like an intensive internship in a setting that intertwines pastoral experience and regular reflection with a peer group and supervisor. During our orientation at the beginning of the summer, all the CPE interns toured the various units of the hospital. When we visited the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, one of my colleagues asked, “How frequently do you have to deal with the death of an infant?” The nurse said, “Oh, we haven’t had a death in ages.”

I was assigned to the NICU for the summer. During my first three weeks, I received four calls for severely premature infants who had died.

In addition to the NICU, I also worked in Pediatric Surgery. Most of the patients had short stays, but I spent a fair bit of time with several who were there for longer visits. Midway through the summer, several of them were discharged on the same day. For most of them, leaving the hospital was great news; they were going home and settling back into a normal rhythm of life. One young boy, however, was not going home. An eight-year-old battling a tenacious spinal tumor, he was moving to a rehab center because he didn’t have a stable home to return to. The day I had met him, I knew he was going to be the one who broke my heart that summer. He was the last one I went to say good-bye to on that day of multiple leave-takings. Afterward, I went down to the river that runs by the hospital. We had sometimes gone there because he liked to watch the trains that passed nearby. I wept for all the good-byes the summer had held, not just within the hospital but beyond it as well.

I thought I had done a good job of collecting myself, but when I went back to the CPE office, the secretary took one look at me and said, “You know what you need to learn, Jan? Oh, what’s that word—detachment.” I bit back a sharp retort. Even at that early point in my pastoral formation, something in me knew that it wasn’t detachment I needed to learn, at least not in the way she was talking about. In that season of farewells, I was coming to see that my work lay in learning how to be fully present to people in whatever way was necessary, to let them draw near, and then, when it was time, to let them go with whatever grace I could muster.

The good-byes never get easy, of course, particularly when they seem premature. So I can really appreciate Peter’s predicament that we encounter in this week’s gospel lection, Matthew 16.21-28. Jesus has turned his face toward Jerusalem and, in so doing, he begins to tell the disciples what awaits him there. Peter cannot abide Jesus’ talk of his coming death. Taking Jesus aside, he remonstrates with him, saying, “God forbid it, Lord! This must never happen to you.” Jesus doesn’t bite back his response. He scolds Peter severely. “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; for you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.”

With breathtaking speed, Peter has gone from being called a rock to a stumbling block. Jesus’ upbraiding of him seems harsh, yet the level of energy he puts into it reflects how important he considers it that Peter understand what he says. Peter, to whom he will give the power of binding and loosing, must learn to let Jesus go.

Jesus is concerned not only that Peter and his companions let him go but also that they learn to release their hold on their own selves. Turning toward the rest of the disciples, Jesus tells them, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life,” he says, “will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.”

Self-denial is a tricky practice, and the Christian tradition hasn’t always done a good job of teaching it. It can be hard, after all, to wrap our brains around the idea that self-denial doesn’t mean giving up who we are at our core, the self that God created us to be. Rather, Jesus’ words here call us to recognize and release whatever hinders us from full relationship with God and one another. Self-denial challenges us to know the stumbling blocks within our own selves. It beckons us to open ourselves to the one who is the source and creator of our deepest self. And self-denial compels us to ask ourselves, “What are the actions, what is the way of being, that will leave the greatest amount of room for God’s love, grace, and compassion to move in and through me?”

The answer to that question won’t be the same for everyone, and that’s another thing that has made self-denial so tricky in the Christian tradition. A single form of self-denial won’t fit for all, and one of the greatest ways we can harm ourselves and others is to follow a path that’s not meant for us.

The desert fathers and mothers of the early church, who flung themselves into a physical and spiritual landscape designed to strip away all that separated them from God, had long practice in discerning the way of life that God intended for them to follow. In Benedicta Ward’s The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Abba Macarius tells a story of meeting two monks, quite naked, who have spent forty years on a tiny island in a sheet of water where the animals of the desert come to drink. At first Macarius thinks the men are spirits, so strange is their presence there. Learning that they are monks of flesh and blood, he asks them, “When the winter comes are you not frozen? And when the heat comes do not your bodies burn?” They tell him, “It is God who has made this way of life for us. We do not freeze in winter, and the summer does us no harm.”

It is God who has made this way of life for us. They know that their way is not for all monks, just as Macarius’s way is not the path that God has made for them.

Jesus tells the disciples, “Let them deny themselves and take up their cross.” He doesn’t say that his followers should take up the cross that will be his own to bear, or that we should carry a cross that someone else has forced upon us. Rather, Jesus compels us to find the particular path that will enable us to do the work of giving up all that separates us from God, from one another, and from our deepest selves. As Peter learned, this includes releasing our desire to dictate the actions of others in ways we are not meant to do, and letting go of our attachment to outcomes that lie beyond our control. “To have without holding,” poet Marge Piercy puts it. In one of the great paradoxes of the spiritual path, it’s this kind of denial—this kind of detachment—that makes way for our deepest connections.

So what are you attached to just now? How do you know when a treasured expectation, desire, or relationship has become a stumbling block? Who or what helps you recognize these blocks? What might you build from them? Can you imagine what lies beyond them?

In your loving and letting go, may you find the way of life that God has made for you. Blessings.

[To use the image “To Have without Holding,” please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]