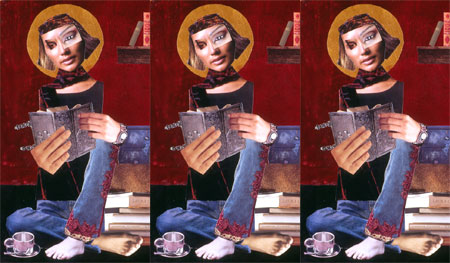

Blessing of the Candles © Jan L. Richardson

In the rhythm of the Christian liturgical year, today marks the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus, also called the Feast of the Purification of Mary. This day bids us remember Mary and Joseph’s visit to the Temple to present their child Jesus on the fortieth day following his birth, as Jewish law required, and for Mary to undergo the postpartum rites of cleansing. Luke’s Gospel tells us that a resident prophet named Anna and a man named Simeon immediately recognize and welcome Jesus. Taking the child into his arms, Simeon turns his voice toward God and offers praise for the “light for revelation” that has come into the world.

Taking a cue from Simeon, some churches began, in time, to mark this day with a celebration of light: the Candle Mass, during which priests would bless the candles to be used in the year to come. Coinciding with the turn toward spring and lengthening of light in the Northern Hemisphere, Candlemas offers a liturgical celebration of the renewing of light and life that comes to us in the natural world at this time of year, as well as in the story of Jesus. As we emerge from the deep of winter, the feast reminds us of the perpetual presence of Christ our Light in every season.

With her feast day just next door, and with the abundance of fire in the stories of her life, it’s no surprise that St. Brigid (see yesterday’s post) makes an appearance among the Candlemas legends. One of those legends reflects a lovely bit of time warping that happened around Brigid. The stories and prayers of Ireland and its neighbors often refer to Brigid as the midwife to Mary and the foster-mother of Christ. Chronologically, this would have been a real stretch, but in a culture in which the bond of fostering was sometimes stronger than the bond of blood, this notion reveals something of the deep esteem that Brigid attracted. In the Carmina Gadelica, a collection of prayers, legends, and songs that Alexander Carmichael gathered in Scotland in the 19th century, he conveys this story of Brigid as an anachronistic acolyte:

It is said in Ireland that Bride [Brigid] walked before Mary with a lighted candle in each hand when she went up to the Temple for purification. The winds were strong on the Temple heights, and the tapers were unprotected, yet they did not flicker nor fail. From this incident Bride is called Bride boillsge (Bride of brightness). This day is occasionally called La Fheill Bride nan Coinnle (the Feast Day of Bride of the Candles), but more generally la Fheill Moire nan Coinnle (the Feast Day of Mary of the Candles)—Candlemas Day.

On this Candlemas Day, where do we find ourselves in this story? Are we Mary, graced by the light that another sheds on our path? Or are we Brigid, carrying the light for another in need?

[To use the “Blessing of the Candles” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of the Jan Richardson Images site helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]