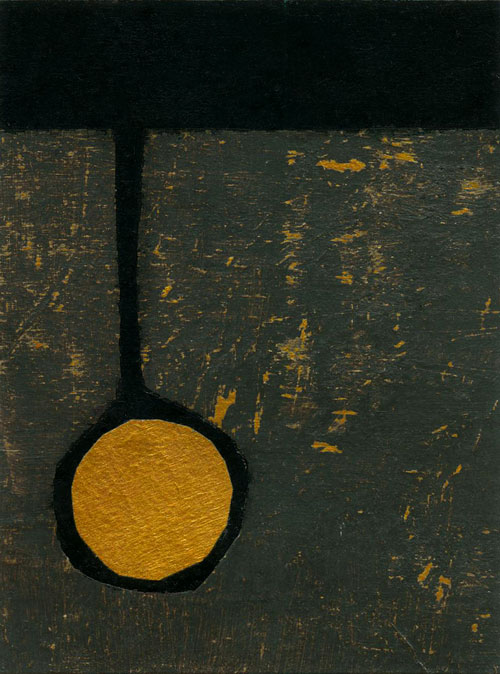

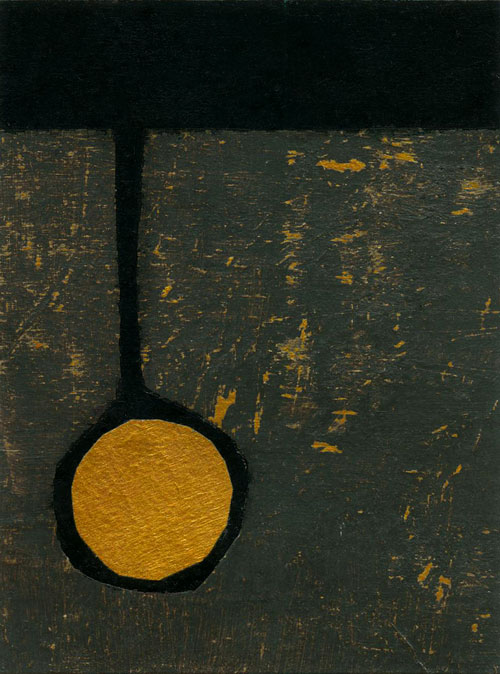

Buried © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 28/Ordinary 33/Pentecost +22: Matthew 25.14-30

So I’ve flown to Toronto, celebrated my sister’s wedding, enjoyed some quality family time (and some crisp Canadian weather), and am winging my way back home as I write. And still those bridesmaids are traveling with me, the ones from last Sunday’s gospel lection. Maybe it has something to do with the synchronicity of their story popping up in the lectionary during the week of my sister’s wedding, but I suspect the persistence of the bridesmaids’ presence simply means they’re not finished with me yet.

It’s the so-called foolish bridesmaids in particular who have lingered with me, the ones who found themselves lacking the oil reserves that would have granted them admittance to the wedding festivities. They’ve been haunting my imagination as curious twins of the wise, well-provisioned bridesmaids. Embodying that which we are urged to reject, the foolish bridesmaids are the wise bridesmaids’ shadow sisters. They challenge us to ponder the part of ourselves that can’t get it together, that is content to live with lack, that is caught in cycles of procrastination and passivity. Their presence calls us to reckon with our resistance toward looking beyond the obvious options.

The foolish bridesmaids appear willing to accept the groom’s verdict, his denial of entry, without question. Perhaps they have forgotten that God performs miracles with oil, as in the story of the hungry widow of Zarephath, who, in her lack, gave hospitality to Elijah, and whose jar of oil was perpetually replenished (1 Kings 17.8-16). The women of Jesus’ parable seem not to know the occasions when God provided water in the wilderness, or the times when Jesus turned a couple of fish and a few loaves of bread into a feast that fed thousands who neglected to pack a lunch, or the story of the woman who told Jesus that even the dogs ate the crumbs from beneath the master’s table, and who thereby won a healing for her daughter. The foolish bridesmaids haven’t heard the story of the widow who hounded the judge until he gave her justice. They haven’t encountered Jesus’ counsel in Luke 11, where, in teaching about persistence in prayer, Jesus invites his listeners to imagine going to the house of a friend at midnight and asking for three loaves of bread for a guest who has arrived. “I tell you,” Jesus says, “even though he will not get up and give him anything because he is his friend, at least because of his persistence he will get up and give him whatever he needs.” Jesus goes on to say, “Ask, and it will be given you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you” (Luke 11.5-13).

Denied entry, these oil-poor bridesmaids don’t know—or don’t care—that they can knock harder on the door that bars them from the wedding feast, and that God has a fondness for those who, faced with two choices, search for Option C.

The Parable of the Bridesmaids is not merely a prelude to the parable of this week’s gospel lection but a parallel to it; in a sense, Matthew 25.14-30 is a retelling of the bridesmaids’ tale. Jesus emphasizes these parables’ parallel nature in the simile with which he starts his story: “For it is as if,” he says, and launches into his narrative of the man who, “going on a journey, summoned his slaves and entrusted his property to them; to one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, to each according to his ability.” And thus begins one of Jesus’ most familiar parables.

We likely know the rest of this story, how one slave turns his five talents into ten, how the next turns his two talents into four, and how the third slave buries his single talent in the ground. On the day of reckoning, the two slaves proffer their profits and receive the expected praise, while the third offers this account: “Master, I knew that you were a harsh man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you did not scatter seed; so I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground. Here you have what is yours.” He receives a thorough castigation for being wicked and lazy. His one talent is given to the man who now has ten, with the master offering this rationale: “For to all those who have, more will be given, and they will have an abundance; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.” The parable ends with the master’s command to throw this “worthless slave…into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Okay, may I just say it? I find myself liking the third servant more than the first two. The entrepreneurial servants of the parable do precisely as expected: they enlarge the master’s fortune in his absence, they follow his plan without question, they perform as he has compelled them to do. The third fellow, however, calls things as he sees them. He knows his master is corrupt, and, with a curious mix of courage and fear, he says so to his face. And thereby reaps the master’s wrath.

So I find myself wondering, why is it that we most often read this passage as a judgment against the third servant and not against the man who has perpetuated an unjust system? Do we really think that the harsh and reportedly corrupt master of this parable represents God, who, after a period of absence, comes back prepared to throw out those who have not performed as expected? Do I really want to be like the first two servants, willing to participate in and perpetuate injustice?

Much like the wise bridesmaids, the two multi-talented men serve as the foil for the one who proves inept and unprepared. One could say they are the suck-ups who provide a contrast to the screwup. We might wonder at a parable that presents a narrative ecosystem in which the only available choices seem to lie either in perpetuating the master’s corrupt business plan or hiding his loot in the ground.

But we might wonder, too, at the servant who perceives these as the only options. He is savvy enough to recognize the system that surrounds him, and, presumably, he has participated in it up to this point. He finally demonstrates a measure of bravery that enables him to, as the phrase goes, speak truth to power. But like the foolish bridesmaids, he possesses a streak of passivity that, within the landscape of the parable, proves his undoing. Perhaps this is what makes each of them—the hapless bridesmaids, the single-talent servant—foolish: ultimately, they prove unwilling to take responsibility for pushing toward another option, looking for another choice. They have forgotten the God who startles with stunning abundance in the midst of the starkest lack.

The servant who buried his sole talent reminds me that when we cannot imagine other possibilities, we tend to hoard what we have, clinging to what is comfortable or at least familiar. And not only to hoard, but to hide. In the absence of eyes to see the wealth that God reveals in the wilderness, we secret away what small measure we have, thinking it will be enough to sustain us, and hoping it will protect us. It’s difficult, however, to draw sustenance from secrets, and it’s hard even for God to bless and multiply that which remains hidden. Darkness has its uses, and its gifts: growth requires gestation, a season of deep shadow, the absence of light for a length of time. But what we leave underground too long grows distorted and becomes decayed. As the third servant discovered, what we hide—our habits, our beliefs, our own selves—has a way of unburying itself.

I take this parable seriously as a profound call to unhide ourselves, to resist accepting the obvious options, to stretch ourselves toward the fullness for which God created us. I recognize how this story, along with the parable of the bridesmaids, warns of the pain that comes from our passivity. Yet I also read this parable in the light of the stories of the God who does miracles with what is most basic and elemental: oil, water, wine, bread, our very selves. This is the stuff in and through which God brings transformation, and the means by which God sustains the world.

This week I find myself wondering, what do I hide, and why? What parts of my created self have I sent underground? Is there anything I’ve left too long in the dark? Do I harbor any passivity that I need to invite God to turn into persistence? As the season of Advent approaches, with its rich play of light and dark, what might God desire to reveal and to transform in my own life?

In these lingering days of Ordinary Time, may God stir our imagination, sharpen our vision, and give us courage to unhide what God desires us to offer. Blessings.

[To use the “Buried” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]