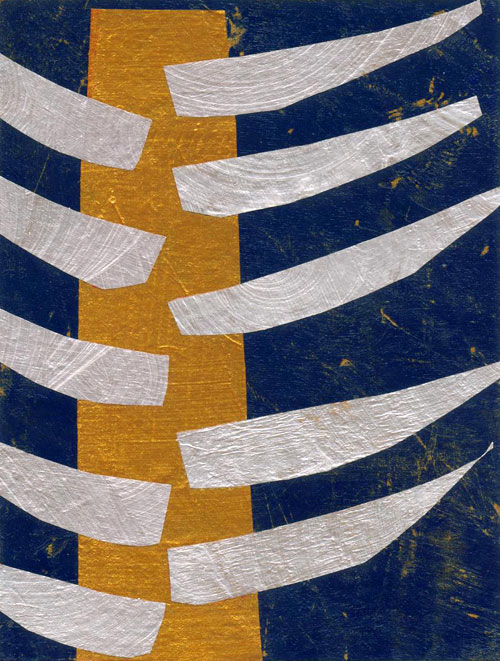

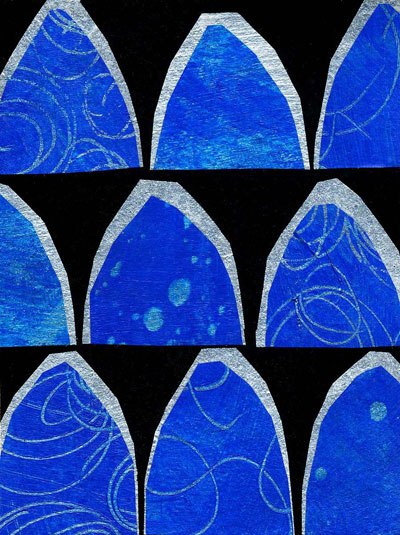

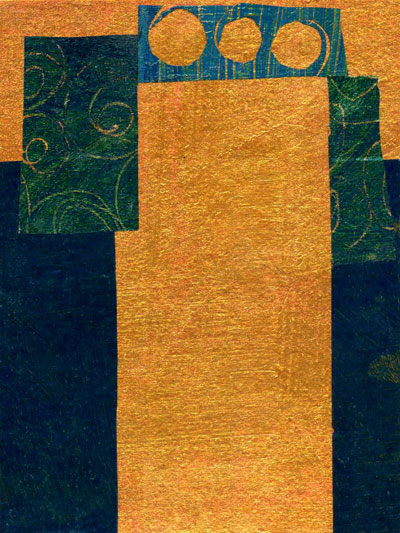

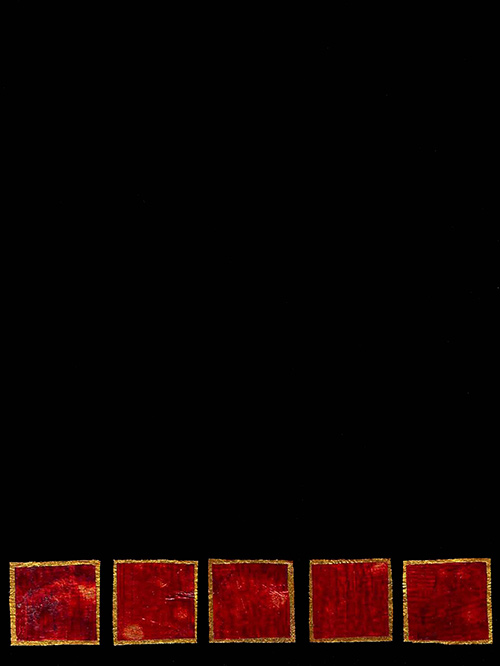

Unbinding Words © Jan L. Richardson

For the entire season of Lent I have been looking forward to this week, because it gives us John 11.1-45 for our Gospel reading. The raising of Lazarus is a Big Story. It takes place at a pivotal place in John’s narrative. The action has begun to intensify; Jesus has just narrowly escaped stoning, and he will soon make his triumphal, if short-lived, entry into Jerusalem. The primary goal of the story is to display Jesus’ power: to demonstrate, as a friend of mine once observed, that Jesus isn’t much impressed with death.

John conveys his point with a richness of texture and detail that makes this a particularly compelling text with which to do lectio divina. The story is dense with movement and meaning, and it offers an extravagance of entry points for reflection.

I am intrigued by the web of relationships among the participants in this text. There are Mary and Martha, whose story is bound together with the unbinding of their brother, and who foreshadow the presence of women at another tomb that lies not too distant. I am curious about the friendship that these siblings shared with Jesus, how their home in Bethany seems to have been for Jesus a particular place of hospitality, comfort, familiarity, and, as John points out, love.

There is Thomas, seemingly destined to forever carry the title “Doubting Thomas,” who ought to be better known as the one who, in this story, demonstrates his willingness to die with Jesus.

There is Jesus, whose presence in the story is marked by waiting and weeping.

And then there is Lazarus. Though the story hinges largely on him, for most of it he is a passive background figure. We never hear his voice, and it is only at the end of the story that he finally becomes really interesting, when he is faced with the choice of whether or not to come out of the tomb.

This story is one of my favorites, not just because it’s a Big Story but because of the way that so many stories come together within it. This is not just Almighty Jesus at the height of his powers, showing off what he is capable of; this is Jesus reaching into the depths of who he is, pouring himself out on behalf of those with whom he is most intimately in relationship. Jesus enacts Lazarus’ raising, but he does so in the context of a community. Jesus calls Lazarus forth, but he calls upon those around Lazarus—sisters, kinfolk, neighbors—to unbind him and let him go.

Despite my fascination with such details that this story offers, and despite the fact that I’ve been looking forward to it for all of Lent, it’s taken me a long while to get my act together on doing the artwork and writing for this reflection. There are a variety of reasons for this. Perhaps it’s best simply to tell you a small story.

I live and work in a studio apartment that’s about 300 square feet. I have one closet. After living here for nearly a decade, the closet has gotten pretty full. My decision to clean it out this week owed to a couple of factors: I was looking for something that I thought was in it, and I am getting myself situated to begin working full-time on a new book. I suspect many writers would tell you that there is no time when cleaning seems more compelling and, in fact, absolutely essential than when there is a new writing project at hand. As a result, my apartment is the tidiest it’s been in a long time. This periodic impulse derives partly from my resistance to writing, but I’ve learned that it’s also part of the process, kind of like a dog who turns around in circles before finally settling down. I experience a strong connection between my external and internal space. Clearing and cleaning and sorting is a way of wreaking some sort of order amid the chaos that attends the writing process.

I had not done a purge of my wardrobe in many years, and, as a result, I wound up with a startlingly large pile of garments needing to be ushered into their next life. I’m not a clothes horse; I don’t even particularly like shopping for clothes, mostly because most clothing stores around here offer a sea of sameness that induces lethargy and saps my will to Try Things On. Despite this, I had managed to amass a sizable collection of clothes that I hadn’t worn in years. I had had some of them since college. A number of the garments held sentimental attachments for me, and I subjected my sweetheart to stories of my two favorite sweaters, received as gifts in college and worn for years, and to lamentations over a few pairs of Birkenstocks that were worn beyond the point of repair but that I could hardly stand to throw away.

This small story is simply a way of saying that I have spent a fair bit of time this week thinking about what I have clothed myself in, what attachments they have held for me, and what I need to let go of. I anticipate you figured out a while back that I’m not talking just about literal clothes. Sorting through the stacks has provided fertile opportunity to wrestle with deeper matters of the patterns with which I garb myself, and to reckon with layers of habits, practices, and routines, not all of which serve me, or my community, well.

The raising of Lazarus is indeed a Big Story. It unfolds, however, in the context of patterns of relationships, choices, habits, and personalities that influence how each character participates in and responds to Lazarus’ raising. Our own lives are built on these same details. We each garb ourselves in routines and practices that carry us through our relationships, our work, our hungers, our lives. Those routines and practices influence how we receive and respond to God’s call. We may be swathed in layers of habits that may have once fit us, habits we may once have found beautiful, habits we may yet be attached to long past their usefulness but which now insulate and shroud us from the presence of God.

The season of Lent beckons us to reckon with our most entrenched habits as individuals and communities: to sort through them and to recognize that Christ, in all his humanity and all his divinity, has power even over them. This season reminds us that the miraculous and the mundane are intimately intertwined. We are called to wrestle with the very details that shape our lives together, that new life may emerge.

So I ask you some of the questions I have been carrying for myself this week: In your daily living, what patterns are life-giving and help you notice the presence of God? Which habits keep you bound? What helps you hear the voice of Christ who stands at the threshold between death and life? What will help you choose to come forth, and to help someone else do the same? Are there people who can help with the unbinding?

May you find the presence of God in every detail.

[To use the “Unbinding Words” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]