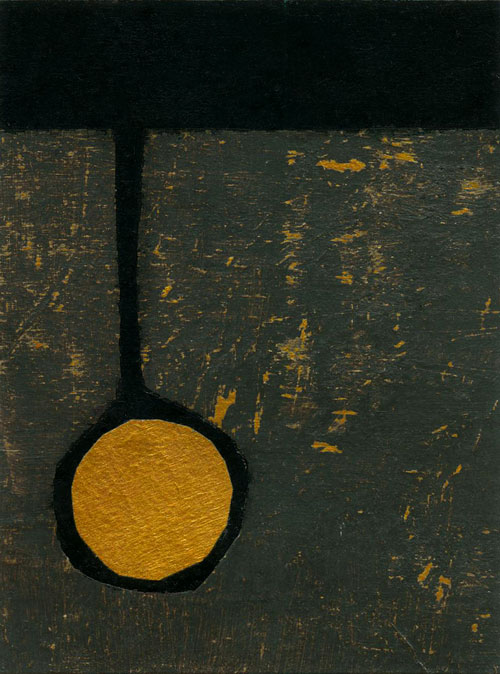

Litany of the Blessed © Jan Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Epiphany 4, Year A (January 30): Matthew 5.1-12

Blessed.

The first time we encounter this word in the story of Jesus, it is in Luke’s gospel. Elizabeth offers this word—repeatedly—when Mary comes seeking sanctuary with her elder kinswoman amidst their mutually miraculous pregnancies.

Blessed are you

among women,

Elizabeth says to Mary,

and blessed

is the fruit

of your womb.

And blessed is she,

Elizabeth says soon after,

who believed.

Blessed, Elizabeth says to Mary: once, twice, and yet a third time.

Blessed blessed blessed.

Barely beginning to take form, Jesus feels the jolt that goes through Mary when she hears this word, blessed. Something in the growing Jesus feels the way the word settles inside Mary when she recognizes it to be true. When she knows it in her bones. When she claims the word for herself as she sings the Magnificat:

Surely, from now on

all generations will call me

blessed.

Blessed. Jesus absorbs this. Blessed seeps into his forming cells, blessed passes from Mary’s flesh into his own. From the womb, he knows the power of receiving a blessing, of living within it. He understands what it means to inhabit this word, to dwell within one who has been named blessed.

Jesus knows this word from the inside. And so there comes a time when he begins to say it. Again. And again.

Blessed are the poor in spirit,

Jesus says to his disciples on the mountain,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn,

he tells his followers,

for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek,

he says to his friends,

for they will inherit the earth.

Again and again, Jesus says blessed, speaks blessed, proclaims blessed, pressing and imprinting it upon his listening disciples.

Blessed the hungry

and thirsty for righteousness,

he says.

Blessed the merciful.

Blessed the pure in heart.

The peacemakers:

blessed.

The persecuted for righteousness’ sake:

blessed.

And you—

you, when people revile you

and persecute you

and utter all kinds of evil

against you falsely on my account;

you—

rejoice and be glad.

You:

blessed.

What Elizabeth did for Mary, Jesus does here for his disciples. What Elizabeth spoke to the one who bore Jesus into the world, Jesus speaks to these whom he will call to become his body, to continue to bear him in this life, to become his hands and feet after his flesh is gone.

Jesus will not cease to say blessed after this passage, this litany, in Matthew 5. He will speak it yet again. When the imprisoned John the Baptist sends his disciples to ask Jesus, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” Jesus tells them to return to his cousin and tell him what they see and hear, of the healing that comes to the blind, the lame, the lepers, and more.

And blessed,

Jesus says to John’s disciples,

is anyone

who takes no offense at me. (Matthew 11.6)

When Jesus’ disciples ask him why he speaks in parables, he speaks of those who have shut their eyes and closed their ears.

But blessed

are your eyes,

Jesus tells them,

for they see,

and your ears,

for they hear. (Matthew 13.6)

When Jesus asks his disciples, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” and they begin to tell of those who say he is the now-slaughtered John the Baptist, or Elijah, or Jeremiah, or another prophet, Jesus asks them, “But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter answers, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus says to him,

Blessed are you,

Simon son of Jonah!

For flesh and blood

has not revealed this to you,

but my Father in heaven. (Matt. 16.17)

Most often, the word blessed—from the Greek makarios—is linked with seeing, with hearing, with understanding. Jesus says blessed to those who recognize him and have responded to his call. He says blessed to those who have opened themselves to him, who have received him. He makes clear that being blessed is available to all. As he is teaching one day, a woman cries out to Jesus,

Blessed is the womb

that bore you

and the breasts

that nursed you!

Jesus responds to her,

Blessed rather

are those who hear

the word of God

and obey it. (Luke 11.27-28)

What Mary did—hearing, seeing, opening, receiving, responding—Jesus invites all his hearers to do. The blessing that imbued Mary—the blessing that Jesus absorbed in the womb and proclaimed throughout his ministry—Jesus tells the crowd is available to them as well.

We often talk about being blessed as if it is a reward, as if good fortune comes to us as just desserts. Much of Christian culture equates blessing with prosperity, with health, with satisfaction and obvious abundance. While it’s tempting to equate these gifts with the favor of God, this notion comes with a corresponding fallacy that says that those who are sick, those who are not prosperous, those whom misfortune has visited: these are not blessed.

With the beatitudes, Jesus utterly disrupts this line of thinking. Being blessed is not a reward for a job well done or for the accident of being born into fortunate circumstances. It is likewise not an accomplishment, an end goal, or a state of completion that allows us to coast along. And although the Greek makarios can be translated also as happy, being blessed does not rest solely upon an emotion: blessing does not depend on our finding or forcing ourselves into a particular mood.

Here in the beatitudes and throughout his ministry, Jesus proclaims that blessing happens in seeing the presence of Christ, in hearing him, in receiving him, in responding to him. And because Christ so often chooses places of desperate lack—those spaces where people are without comfort or health or strength or freedom, those places where they hunger for food or mercy or peace or safety—it is when we go into those places, when we seek and serve those who dwell there, that we find the presence of Christ. And, finding, then carry him with us.

To be blessed is not a static state. There is a dynamism within the word blessed: it implies an ability to be in the ongoing process of recognizing, receiving, and responding. To be blessed is to enter a kind of pregnancy: to take Christ in, to let him grow in us, to bear him forth, then to receive him and bear him yet again in our acts of mercy, of compassion, of solidarity, of love.

And you? Who or what do you name as blessed? Where do you encounter the blessing of Christ in this world? How do you seek to embody the blessing of God in your own life—to see and to hear Christ, to recognize him and bear him? Do you think of yourself as blessed? Who has given you this name? Who have you named as blessed?

May we have eyes to see and ears to hear, and may Christ have cause to say to us:

Blessed are you.

Blessed are you.

Blessed are you.

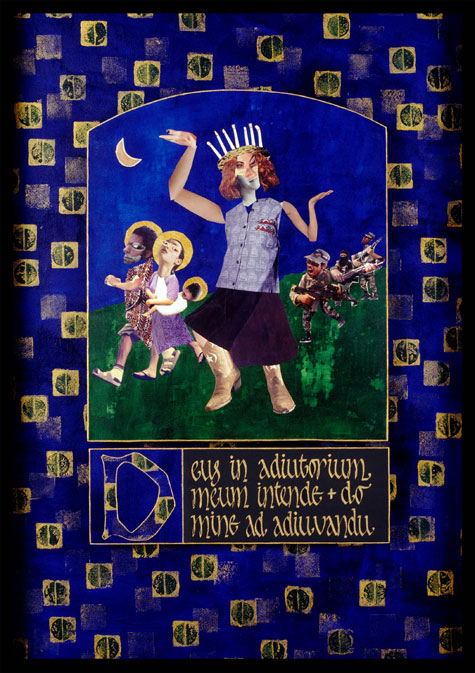

[To use the “Litany of the Blessed” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

P.S. Coming Attractions: I’ve recently updated my Upcoming Events page. Would love for you to join us for any of these events if you’re in the vicinity!