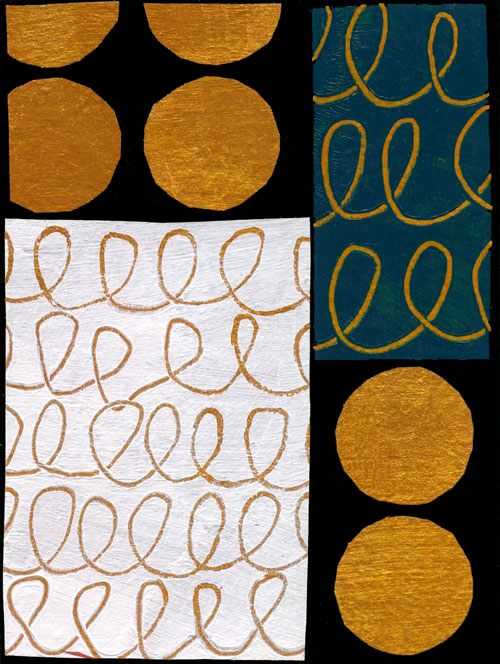

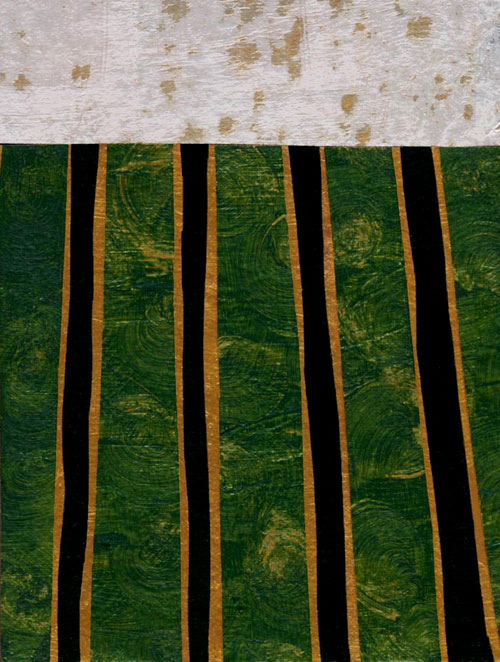

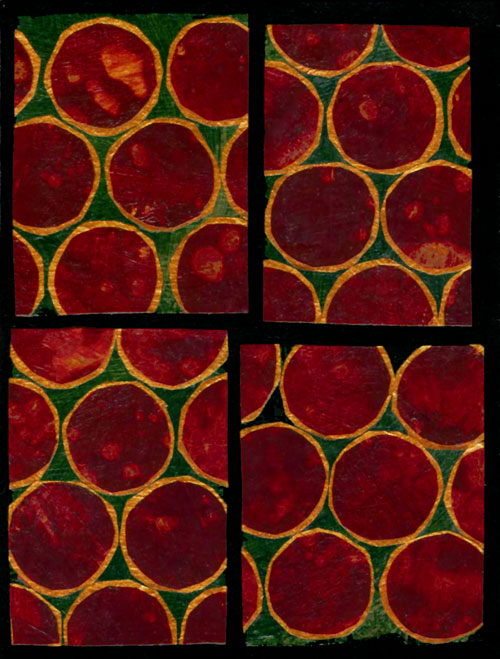

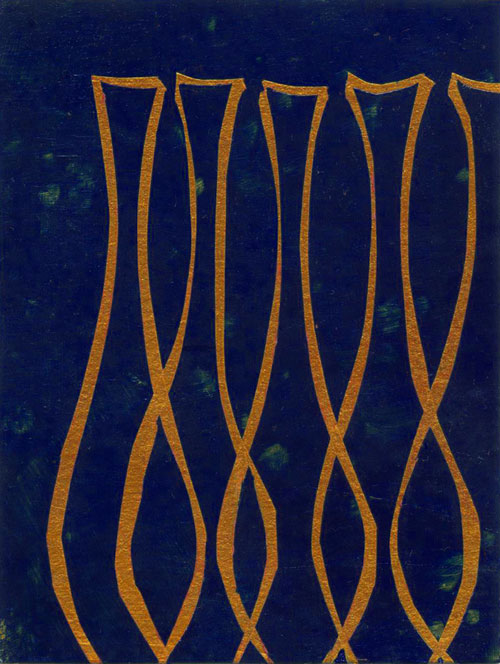

Midnight Oil © Jan L. Richardson

Well, my suitcase has just barely finished cooling off from my recent trip to Seattle, and already I’m packing again. This week I’m heading to Toronto, with joyous cause: my sister is getting married. I have received official approval from the Canadian government to perform the wedding, learning along the way that the wheels of bureaucracy turn at about the same speed across international borders. I am grateful to the folks who provided support and endorsement in the process, including a couple of officials in The United Church of Canada, the denomination that served as the “governing authority” that, per Canadian requirements, sponsored my application. The wedding will be small and sweet. I’m working to resist the urge to ask my Canadian-transplant sister, when it comes time in the ceremony, “So, you take this man, eh?”

So I have matrimony on my mind, which coincides well with this week’s gospel lection. Matthew 25.1-13 offers the Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids, which has sometimes been referred to as the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, owing to the pronounced distinction that the parable makes between the two groups. As was the case with the Parable of the Wedding Banquet that we visited just a few weeks ago, this lection offers a setting that calls to mind my wedding anxiety dreams, which generally fixate on some aspect of not being ready for the big event. With its emphasis on being prepared, our story at hand does little, on the surface, to alleviate my lurking anxieties.

This is a tale to leave procrastinators quaking. Jesus’ story provides little solace for those of us who struggle with being prepared and timely. There seems to be no help here for the five bridesmaids who lack the oil necessary to trim their lamps. The five wise bridesmaids certainly don’t offer any aid. These bridesmaids may be well stocked with oil for their lamps but they seem dramatically lacking in grace toward those who find themselves oil-poor.

Fortunately, Jesus has plenty to say elsewhere about grace, and I don’t think that’s the primary issue he’s trying to tackle in this parable, though grace does surface in a roundabout manner. With this story of the bridesmaids, Jesus beckons his hearers to give thought to their own role in their relationship with the divine. He lifts up the necessity of taking personal responsibility, a quality not always embraced these days. The good news in this parable, and in the Christian faith, is that we do not have to look to someone else to mediate our relationship with Jesus, nor does our inclusion in the body depend on access to special secrets. This parable implies that wisdom comes not in having hidden knowledge; even the wise bridesmaids didn’t know what time the bridegroom would show up. Rather, wisdom lies in discerning and cultivating what is ours to offer. The wise bridesmaids may seem graceless, but providing for everybody isn’t the bridesmaids’ job here. It’s one occasion where taking care of everyone else isn’t a woman’s responsibility. The wise women of this story instead call us to attend to that which will deepen our relationship with God and hone our ability to receive God’s ever-present grace.

The wise bridesmaids do what is necessary to provide light. In the context of the teaching that Jesus is doing here about the kingdom of heaven and the end of days, it’s good to remember that, at its Greek root, the word apocalypse means to reveal, to uncover, to unhide. The bridegroom is meant to be seen when he finally arrives (as is the bride, who, though some of the most ancient manuscripts of Matthew include a reference to her, for the most part is curiously absent from this story). The bridesmaids, these women, are the ones who provide the light by which the celebrants may see the groom.

Later in this chapter Jesus will become quite specific about the sorts of actions that provide light for the world—the radical stuff of feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting prisoners. Jesus means for these light-bearing bridesmaids to inspire and model for us what it means to perceive the presence of Christ among us and to minister to him in the infinite and surprising variety of forms that he takes. This parable, in fact, offers a powerful resonance with the gospel stories of the women who, seeing Jesus and recognizing who he is, anoint him with oil in a lavish fashion.

We have to be cautious with this text, however, lest it tempt us to think Jesus’ point is all about work—that our invitation to the party depends on what we do. All ten bridesmaids, after all, were invited to join in the celebration. And all ten fell asleep, so, though Jesus admonishes his hearers to stay awake, it wasn’t solely for somnolence that the unwise bridesmaids were denied entrance. Evidently what makes the wise bridesmaids wise is that they know what it takes to make a party. We need light, that we may see one another and know one another. We need light so that we may recognize the one who beckons us to join in the feast, not because he wants only to put us to work but also because of the sheer fact that he desires our company and delights in our presence.

When I was in seminary, I heard Jim Wallis, one of the founders of the Sojourners community, tell a story about a colleague living in a village in Central America. She worked in a community that was marginalized in all kinds of ways. She poured herself into her work for social justice, laboring with great might to bring change to this village. One day, some of the people of the village came to her, asking her why she worked so hard, why she didn’t join them in their fiestas or sit with them in their porches in the evening.

“There’s too much work to do!” the laboring woman replied. “I don’t have enough time.”

“Oh,” the people of the village said. “You’re one of those.”

“One of who?” the woman asked.

“You are one of those,” they responded, “who come to us and work and work and work. Soon you will grow tired, and you will leave. The ones who stay,” they said, “are the ones who sit with us on our porches in the evening and who come to our fiestas.”

Jim Wallis said that his colleague took the story to heart, that she became a party animal, and that she was still there.

There is work to do: flasks to be filled, lamps to be lighted, long nights ahead that call for labor and readiness instead of rest. Especially with Advent approaching, it’s a good time to ask ourselves what it is we’re getting ready for, and how, and why. It’s a good time, too, to ponder how, and whether, we are seeking sustenance for our own selves. We cannot find or fashion light merely by our own efforts; it comes not solely with labor but by opening ourselves to the light of Christ that we find as we linger with one another.

This is the place where I would normally ask what practices help you cultivate your openness to the God who calls us to the celebration—what are you doing to keep your oil flask full? But I find myself thinking of the fabled story from the desert fathers, the one where Abba Lot goes to Abba Joseph and recites the list of practices by which he’s seeking the presence of God: praying, meditating, fasting, etc. “What else can I do?” he asks. Old Abba Joseph stands up and stretches his hands toward heaven. His fingers, the story says, become like ten lamps of fire. “If you will,” Abba Joseph says to Abba Lot, “you can become all flame.”

And so I want to ask, not just how are we keeping our oil flasks full, not just how we’re taking care of our lamps, but how might we ourselves become all flame? What are we burning for? How do we become people who do not merely carry well-provisioned lamps but who are vessels of living light, illuminated by the one who called himself the Light of the World?

On this dark November night, this prayer: For one another, with one another, may we blaze.

Blessings.

[To use the “Midnight Oil” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

[Abba Joseph story from The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward, SLG.]