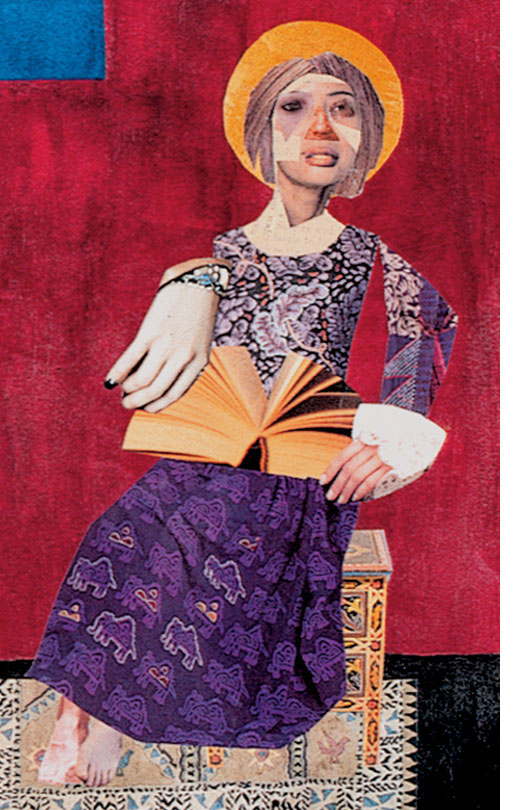

© Jan L. Richardson ◊The Painted Prayerbook◊

So, did you sense the shift when we moved into the new season? Did you hit the after-Pentecost sales and send out your “Merry Ordinary Time” cards? No? It tends to sneak up on us, doesn’t it, this new and subtle season of the Christian year. We have spent the past six months swimming in the Big Stories that Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Pentecost provided for us. These holy days and seasons have offered something approaching an embarrassment of riches with the themes they have brought us: birth, incarnation, the wilderness, suffering, death, resurrection, the life of the community, and the work of the Holy Spirit. It’s been a good and grounding groove.

And now for something completely different.

Ordinary Time officially began with the ending of Pentecost, and with Trinity Sunday now behind us, the new season is upon us in earnest. Stretching out for the next six months, Ordinary Time invites and challenges us to move into a mode that is shaped by something other than the “high seasons” that the past half-year has offered us. I sometimes find this new rhythm a little disorienting at first. Living in Florida, where the natural seasons are present (really, we do have them) but subtle, I rely on the liturgical year to help me tell time. Without the big markers I’ve been living with for the past six months, the days and weeks sometimes seem like they’ve lost their cohesion, that they’re oozing out into a nearly interminable horizon that holds few occasions for liturgical celebration. Plus, it’s a really long stretch of looking at green paraments every Sunday.

This season, however, beckons us to find the sacred in its subtlety. In the introduction to her book The Time Between: Cycles and Rhythms in Ordinary Time, Wendy M. Wright reminds us that the “ordinary” in “Ordinary Time” does not mean “boring, uneventful, undistinguished, everyday.” Rather, it “comes from the word ordinal, to count.” With its being a seemingly in-between time, however, Wright observes that this season holds us in a different way than do the seasons “when the beauty of the faith is etched in high relief.” She writes,

I like to think of the entire spectrum of the liturgical cycle of Ordinary Time with all its varied rhythms—of Sunday observance, daily prayer, the sanctoral cycle, the tapestry of stories that dramatize the call and response of Jesus and the first disciples, the seasons of our own discipleship throughout the life cycle, the ritual practice of the great Christian rites, the dynamics of our inner faith lives—as one greater movement of desire to be face-to-face, heart-to-heart with God. The deep grammar of the church year’s Ordinary Time is perhaps uttered most keenly in our ceaseless longing. By it we are propelled into the future. We pine for it as past. We trace the surface of the present with anxious fingertips. Call our desire awareness, mindfulness, mysticism, aesthetic sensitivity, faithfulness, or whatever. It is the fundamental movement of the Christian life.

Given the intensity of the stories that have accompanied us during the months between Advent and Pentecost, one might be tempted to think that Ordinary Time gives us something of a rest. It offers us a different rhythm, to be certain, but as we move into this season, the lectionary doesn’t let us off the hook. The Gospel lection for this Sunday, Matthew 6.24-34, challenges us with questions that lie at the heart of Christian life: Whom will we serve? Where will we place our trust and our energy?

To pose these questions, Jesus turns, in his typical incarnational way, to a couple of earthy examples at hand: the birds of the air and the lilies of the field. Urging his disciples not to devote themselves to worry and anxiety, he borrows the well-fed birds and well-clad lilies as signs of how God cares for God’s creatures.

I have to say that living without worry seems pretty easy to do if you’re a creature who can get by on worms and water. For the rest of us, giving up anxiety often seems more of a challenge. I’ve been pondering this Gospel passage in the midst of hearing news of the mounting death count from the earthquake in China and the cyclone in Myanmar. And I’ve been contemplating Jesus’ words with an awareness, too, of the daily terrors and suffering that shape the lives of so many on this planet. How is it, I wonder, that God has provided, is providing, will provide for their needs? What do Jesus’ images of birds and lilies look like in places that seem devoid of beauty and care?

I was reflecting on this with a couple of friends at lunch today. We each know how little we have in the way of answers to these kinds of questions, other than a sense that somehow God is present in the rubble, literal or otherwise, that disasters leave behind. One of my friends, a Benedictine, reminded us of St. Benedict’s words in chapter 4 of his Rule. After he has provided his monks with a lengthy list of what he calls “The Tools for Good Works,” Benedict wraps up this chapter by writing, “And finally, never lose hope in God’s mercy” (Rule of Benedict 4.74).

Wrestling with this week’s lection, I find myself wondering not so much how to keep myself from worrying but wondering instead how I might be called to relieve someone else’s worry, to be part of the way that God provides clothing and shelter and solace for someone. How do I live as someone who not only hopes for God’s mercy, for myself and others, but participates in that hope by becoming a sign and a vessel of God’s mercy in this world? As someone whose ministry involves raising my entire income, and who lives with the ordinary causes of worry that so many of us deal with, I’m not unacquainted with anxiety. At the same time, I’m aware of how the presence of persistent worry and anxiety may be a sign that I’ve become too absorbed by my own concerns, too consumed with my own needs, and that I need to allow God to draw my attention beyond myself to attend to those who need something that I can offer. It’s a way of trying to do what Jesus, at the beginning and ending of this Gospel lection, challenges us to do: to choose whom we will serve, and to focus first on the kingdom of God, that all other things in our lives may fall into their rightful places.

As we set out into this season of Ordinary Time, where is your energy going? What—and whom—are you serving? What worries, anxieties, needs, and desires are shaping your days? How might you invite God to transform your anxiety into acts of hope, mercy, and love in this world?

Deep blessings to you in these ordinary days.