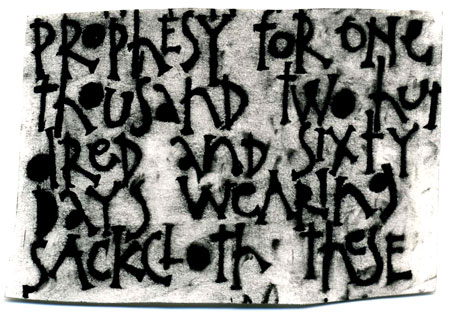

Recently, in opening a book that I hadn’t looked at in a few years, I came across this scrap of paper. The book in which I found it is a large one that I keep tucked beside my drafting table, in one of those nooks that I’ve had to carve out as a reader who lives in a small space. I was a little perplexed as to how the scrap got there; normally I don’t use charcoal-laden paper as a bookmark, and I hadn’t opened the book since sometime before I had charcoaled those words in the first place. I think the scrap must have fallen off my drafting table at just the right angle to wedge itself between the pages.

Here in the season of Lent, it was a curious piece to come across, with its stark, ashy letters and its mention of sackcloth. This was an early practice piece from a series I did a couple of years ago. Inspired by medieval illuminated Apocalypses, I created a series of a dozen pieces that incorporated charcoal drawing and lettering. It was the first time I had combined letters with my charcoal work, and it took—well, let’s just say it took a loooooong time to work out the challenges that came in doing the layouts for those pieces. (See the results at The Intimate Apocalypse.)

As I worked on designing the lettering style (typically called a hand) for this series, I went through some old issues of a wondrous magazine called Letter Arts Review. Looking at LAR tends to be a mixed experience for me. It’s a source of inspiration and a way of cultivating my visual vocabulary. At the same time, I don’t think I’ve ever gotten through a whole issue without feeling stabs of envy at the amazing work that others have done.

I’m learning to engage envy as I (try to) engage any other difficult emotion: as a signal, an invitation, a message that there’s something here I need to work on. I find that envy offers a couple possible messages. When I feel envious of the work of others, it might be an invitation to stretch into a new direction in my own work. At the same time, envy may be challenging me to become more clear about my own direction, my sense of creative vision, my own call. In this case, envy over another person’s work beckons me to go deeper into my own work.

The creative process is, of course, a form of practice. Dealing with envy and other challenging emotions that emerge along the path of our practice is, in itself, a form of practice; it’s part of the process of honing our focus and wrestling with what distracts us. If I give it some attention, try to listen to what it has to tell me, envy can deepen my practice; if I ignore it or if I obsess over it, it can sabotage my practice.

There’s a poem by Rumi that I keep returning to as I continue to learn what it means to practice. In Coleman Barks’s version of Rumi’s poem “The Sunrise Ruby” (from The Essential Rumi), the poet writes about how giving ourselves to a daily practice is like knocking on a door:

Keep knocking, and the joy inside

will eventually open a window

and look out to see who’s there.

But here’s the catch: we need to be knocking on our own door, not someone else’s. We can visit other doors, peek across their thresholds for inspiration and guidance, and converse with those who dwell inside. If, however, I’m going to move deeper into the work that I’m here to do—if, as Rumi writes, I’m going to find what dwells on the other side of the door—I need to cultivate the particular practices that will work for me, not for someone else.

How do you discern which door to knock on? What practice or practices help you discover and move deeper into the work that is yours to do?

A blessing upon your knocking.