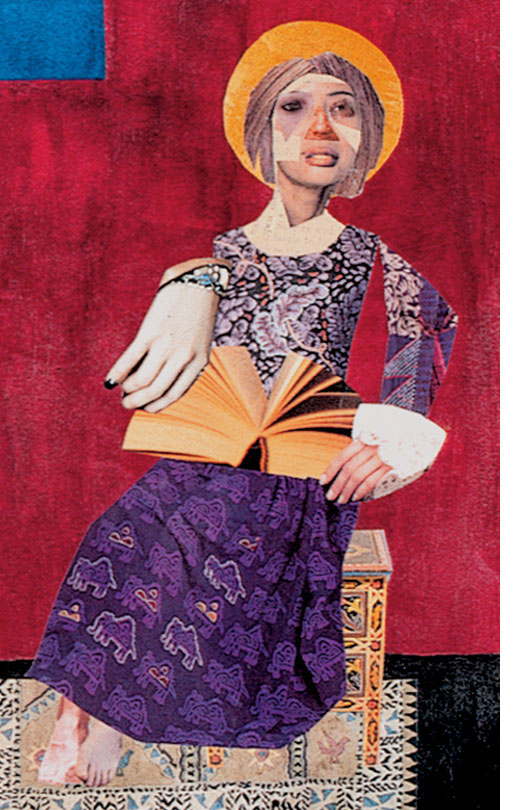

Violence in the Vineyard © Jan L. Richardson

Reading from the Gospels, Year A, Proper 22/Ordinary 27/Pentecost +16: Matthew 21.33-46

For the third week in a row, the gospel lection offers us a vineyard. Jesus saved the most challenging one for last. In the passage for this Sunday, he relates the parable of a vineyard owner who sends servants to collect the produce at harvest time, and of tenants who meet the servants with brutal attacks and murder. The landowner sends a larger party of servants, who meet with the same fate. The landowner sends his son, thinking the tenants will respect him; instead, they throw him out of the vineyard and murder him, thinking they can get his inheritance.

It is a vineyard drenched with violence.

To his listeners, Jesus poses this question: “Now when the owner of the vineyard comes, what will he do to those tenants?” They respond, “He will put those wretches to a miserable death, and lease the vineyard to other tenants who will give him the produce at the harvest time.”

This passage offers some puzzles, not least of which is the violent setting that Jesus employs to drive home his message about the kingdom of God. He has been pressing his hearers to understand that the kingdom will include many folks whom they don’t expect it to encompass. As we’ll see next week, Jesus is not yet done with that crucial point. He’s turning up the heat, in fact, and the images he is choosing for his parables are becoming increasingly raw and disturbing—a fact not lost on his hearers. This week’s lection poses a challenge with the manner in which Jesus—or his listeners, at least—implies an image of God as one who seeks violent retribution.

Yet this lection offers, too, some tantalizing treats for the exegete. Its imagery, for instance, draws on the Song of the Vineyard in Isaiah 5, in which the prophet sings of an allegorical vineyard much like the one in this week’s parable:

My beloved had a vineyard

on a very fertile hill.

He dug it and cleared it of stones,

and planted it with choice vines;

he built a watchtower in the midst of it,

and hewed out a wine vat in it;

he expected it to yield grapes,

but it yielded wild grapes. (Isa. 5.1b-2, NRSV)

For yielding wild grapes instead of cultivated ones, and for the bloodshed that takes place within its borders, the vineyard is made a wasteland.

In this week’s Matthean passage Jesus draws also on the book of Psalms, quoting from Psalm 118, in which the psalmist offers thanksgiving for receiving deliverance in battle. It is the final psalm in a series called the “Egyptian Hallel,” a group of psalms that formed part of the liturgical celebration at festival times. This is how Jesus quotes it:

The stone that the builders rejected

has become the cornerstone;

this was the Lord’s doing,

and it is amazing in our eyes.

I am intrigued by how the gospels preserve bits of the Hebrew scriptures, and by the texture that this intertextuality brings. It serves as a reminder of the way in which the gospels find their grounding in the scriptures that originated with the Jewish people—the canonical matrix or generative milieu, as Richard B. Hays terms it. It’s particularly good to notice the richness of this inheritance at this point in the calendar: we are in the midst of the High Holy Days of the Jewish year, known as the Days of Awe, a ten-day period that began with Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) on September 29 at sunset and will conclude with Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), which begins at sunset October 8.

There is much to sort through among the treasures and challenges in this week’s lection. In contemplating this passage in the space of lectio divina, I have been drawn to remember how practice of lectio invites us to enter a text in much the same way we might ponder a dream, recognizing that each part contains and reveals some piece of our selves. And so what’s surfaced and persisted with me has revolved around this question: What’s going on in the vineyard of my soul?

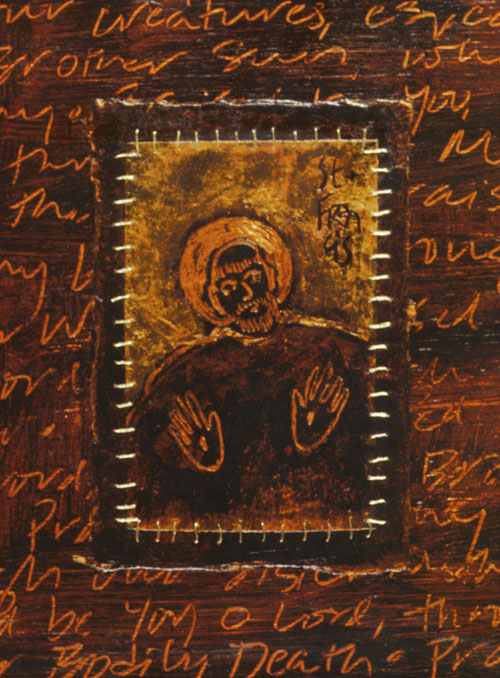

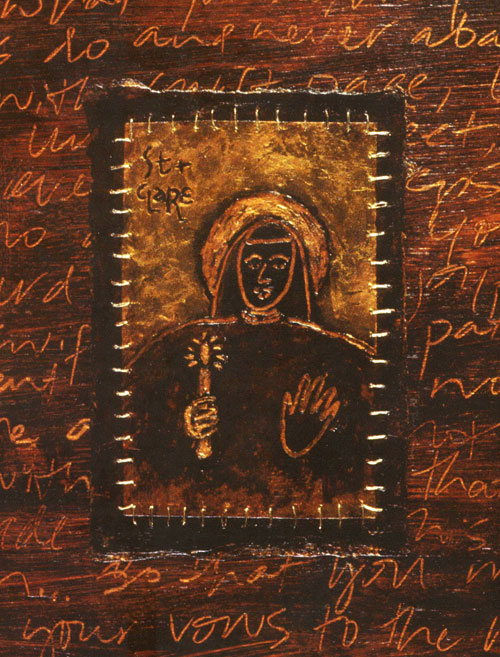

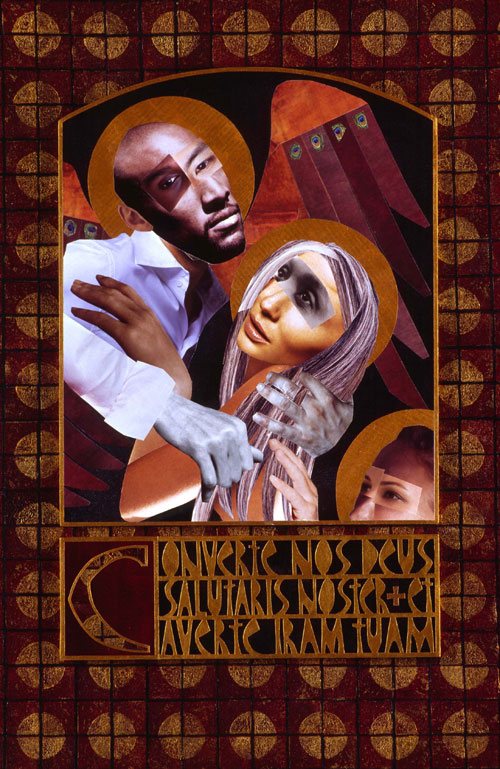

As often happens, creating this week’s collage was part of what got me to that question, and to the other questions that came in its wake. I initially worked on a design that was dramatic, thinking that something vivid and explosive and sharp would evoke the violence of this parable. As I continued to play with the papers, however, I found myself thinking how often violence begins in small ways. It rarely starts as something explosive; rather, it works to find tiny openings, just enough space to wedge itself into. Violence finds its sustenance and its home in the actions that accumulate over time: impatience, indifference, working beyond our weariness, depleting our internal reserves, relying too much on ourselves, pushing anger underground, making assumptions, giving ground to prejudice, stoking resentments… So many ways we till the soil, inadvertently and otherwise, where violence can take hold.

I don’t think of myself as a violent person, and yet lately there are some heads I’ve felt the impulse to pinch. So it’s a good week to be wrestling with this text, and checking my assumption that I’m not a violent person, and asking myself, How am I cultivating my vineyard these days, and what am I allowing to seep in—even stuff that seems tiny, microscopic, really, but can take root over time?

I’ve found myself thinking again of Etty Hillesum, the brilliant young Jewish woman who was killed in the Holocaust. As I’ve written about elsewhere, Etty persisted in tending her soul as the world was falling apart. She understood that violence doesn’t spring forth fully formed, that it gestates in small acts and individual hearts, and that when we don’t attend to what’s going on inside us, the destructiveness within us accumulates and spills over into the world around us. Shortly after appearing at a Gestapo hall where she and other Jewish people had been summoned for questioning, Etty wrote in her journal,

Something else about this morning: the perception, very strongly borne in, that despite all the suffering and injustice I cannot hate others. All the appalling things that happen are no mysterious threats from afar, but arise from fellow beings very close to us. That makes these happenings more familiar, then, and not so frightening. The terrifying thing is that systems grow too big for men and hold them in a satanic grip, the builders no less than the victims of the system, much as large edifices and spires, created by men’s hands, tower high above us, dominate us, yet may collapse over our heads and bury us.

One of the practices that Etty cultivated in the midst of the Holocaust was a refusal to give in to hatred. She recognized hatred as a form of violence that would not solve the terror that the Nazis were inflicting. “I see no alternative,” she once told a friend, “each of us must turn inwards and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others.”

66 years ago this week, Etty wrote in her journal, “Ultimately, we have just one moral duty: to reclaim large areas of peace in ourselves, more and more peace, and reflect it toward others. And the more peace there is in us, the more peace there will also be in our troubled world.”

It’s a challenge, this peace thing, especially since it specifically does not mean refusing to see the violence that persists in the world or pretending it isn’t there. It doesn’t mean being spineless, doesn’t mean letting the bullies win, doesn’t mean standing by while others are destroyed. Whatever peace doesn’t mean, I do know it includes seeking it within our own selves, cultivating it in the vineyard of our own souls, recognizing that what grows there is intertwined with what grows in the world beyond our own borders.

So what’s growing in the vineyard of your life? What do you cultivate with intention? How do you pursue peace there? Is there anything you have allowed to seep in, to take root by stealth? What practices help you tend that field?

Yesterday morning, praying the Office of Lauds from the breviary that the St. Brigid’s community uses, I came upon this line in the litany: “Alert us to the peace we can impart to others out of the full store of your blessings.” In the days to come, may we be alert indeed to this peace, and tend it, and lavish it on one another. Blessings.

[To use the “Violence in the Vineyard” image, please visit this page at janrichardsonimages.com. Your use of janrichardsonimages.com helps make the ministry of The Painted Prayerbook possible. Thank you!]

[Richard B. Hays reference from his essay “The canonical matrix of the gospels” in The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels, ed. Stephen C. Barton. Etty Hillesum quotations from Etty: The Letters and Diaries of Etty Hillesum 1941-43, edited by Klaas A. D. Smelik.]